Mentoring often starts simply. During a class in Olin Physical Laboratory. A study-abroad experience. A chance encounter outside Reynolds Gymnasium. Those moments when a professor and students connect can inspire students to do things they never considered possible.

As Professor Pete Brubaker (MA ’86, P ’17) describes it, the connections can come in a flash, in “30-second, unplanned conversations.”

Thirteen years ago, Wake Forest Magazine featured stories of students and the professors who challenged, guided and inspired them. We reached out to several of them recently to learn if their mentoring relationships have continued.

Some of the students — now alumni — and professors have built on those bonds to become lifelong friends and collaborators. While they might not talk every week or see each other that often, they know they can depend on each other. The professors continue to offer career and life advice, but now they reach out to their former students for help as well. The alumni are paying it forward by becoming mentors for the next generation of students.

Illustration by Jean-Manuel Duvivier

Oana Jurchescu

Baker Family Professor of Physics

& Katelyn Goetz (’11, Ph.D. ’16)

Research scientist, National Institute of Standards and Technology

KATELYN GOETZ WAS a physics major determined to focus on what she wanted to do when she started working with Professor Oana Jurchescu in 2010. “I was very opinionated about which project I wanted to work on,” she says.

Her professor welcomed Goetz into her research group in the physics department, where they found that their personalities, research interests and scientific philosophies meshed.

“I was quite impressed to see an undergraduate having such a well-defined vision on what they like to work on,” Jurchescu says.

Their undergrad student-professor relationship grew. Soon, with Jurchescu’s guidance, Goetz was making a presentation at an international conference in Dresden, Germany. Goetz stayed at Wake Forest for her doctorate and received National Science Foundation fellowships to continue her work with Jurchescu, who was amassing Wake Forest awards for excellence in teaching, research and mentoring. The two women co-authored 19 articles in scientific journals and one book chapter while Goetz was at Wake Forest.

Jurchescu and Goetz in 2012<br /> Photo/Ken Bennett

Goetz spent four years in Germany in post-doctoral positions before she returned to the United States and joined the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) in Washington, D.C. She and her husband, Alex Taylor (’09, Ph.D. ’16), also a physicist, live in Gaithersburg, Maryland.

Goetz

Goetz’s research focuses on how to use organic semiconductors for sensing applications, including electric or magnetic fields. Jurchescu researches organic electronic materials and exploits the main attributes of plastic to create wearable electronics and flexible electronics such as solar panels, devices for medical applications and rollable displays for smartphones and TVs.

Goetz’s work in Jurchescu’s lab influences Goetz’s research today. “It was very fortuitous for me to work with Oana,” she says. “Her research … fit my interests very well, and I have more or less stuck with the area since then.”

There’s no greater reward than seeing a curious, eager student become a confident researcher, Jurchescu says: “The best part of my job is mentoring and being part of the (students’) growth process and guiding them.”

Jurchescu

Mentoring has a ripple effect. Goetz mentored younger students at Wake Forest when she was a Ph.D. student and won the physics department’s outstanding peer-mentor award. She has also mentored community college students at NIST and recruited one of Jurchescu’s students to work with her at NIST. She learned from Jurchescu to give students trust, respect and the time and space to learn from their own experiments — and mistakes — in the lab.

Goetz and Jurchescu remain in close contact. “Oana has gone from my boss and mentor guiding my research, and now we’ve grown into collaborators and friends,” Goetz says.

“The way Katelyn has grown her expertise does not perfectly overlap with my expertise,” Jurchescu says. “If I need something, and I know that Katelyn can do it, I’ll say, ‘Katelyn, here’s what we need. Can you help us with this?’”

Pete Brubaker (MA ’86, P ’17)

Professor and chair of health and exercise science

& Rob Musci (’12)

Assistant professor of health and human sciences, Loyola Marymount University in Los Angeles

FIFTEEN YEARS AGO, then-sophomore Rob Musci was leaving Reynolds Gymnasium when he ran into his physiology professor, Pete Brubaker. Musci had a question for him: Can I help you with any research?

Brubaker, who was investigating the effects of a Mediterranean lifestyle on cardiovascular health, had the perfect project for him. He asked Musci, who’s fluent in Italian, to translate a pile of surveys completed by residents of Venice.

“There was just something about Rob,” Brubaker says. “Sometimes, it’s those 30-second, unplanned conversations that just happen at the right time that can be life changing.”

Brubaker and Musci in 2011<br /> Photo/Heather Evans Smith

Musci and Brubaker bonded over similar interests and a love of running and the ultimate challenge — fighting through fire, water and mud along a 10-mile Tough Mudder obstacle course designed by British special forces.

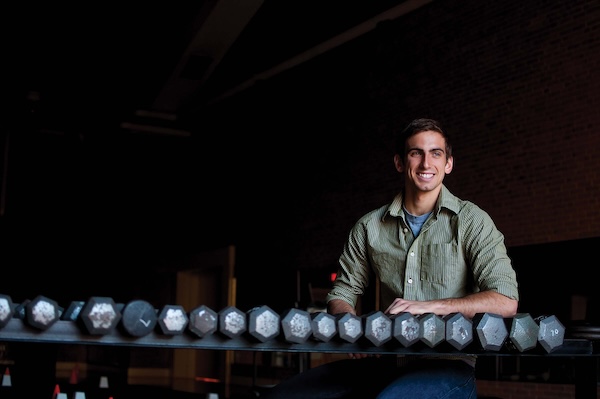

Musci

Musci might not have known it then, but he had found a mentor and role model. That opened the door for what followed in his education and professional journey, he says. “Every step of the way, I’ve talked to Pete.”

As their relationship grew from student-professor to collaborators, Brubaker encouraged Musci to spend time in Venice and research Venetians’ patterns of physical activity and their risk for chronic diseases. Musci studied at Casa Artom as an undergraduate and was a resident assistant there after he graduated.

Brubaker

Musci earned his master’s degree from Colorado State University and received a Fulbright award to conduct research in Italy and build on Brubaker’s work. Brubaker happened to be teaching at Casa Artom at the same time, and he asked Musci to help him teach a class.

“That was really the starting point of the evolution” in becoming a teacher, Musci says. “The same goes with the research in Venice, where I made so many mistakes and learned so much along the way. Pete was always guiding me.”

Musci in 2011<br /> Photo/Heather Evans Smith

When Musci was completing his doctorate in human bioenergetics at Colorado State, Brubaker worried that his mentee was making a mistake as he moved toward a career in research. But it wasn’t his place to tell Musci that. Instead, he reminded Musci how much he loved teaching and working with students.

Musci took that advice to heart. He had always admired how Brubaker balanced career and family, teaching and research, and building relationships with students and colleagues. He wanted the same balance and found it at Loyola Marymount, where he teaches undergraduates and researches aging and chronic diseases.

He still looks to Brubaker for inspiration as he mentors his own students. Brubaker now calls Musci for help, too. “At some point, the mentor becomes the student; the student becomes the mentor,” Brubaker says. “I can admit that Rob knows a whole lot more about (some areas) than I do, and I can learn from him. Part of being a good mentor is realizing that it can be flipped the other way.”

When Brubaker found out that he was going to be teaching at Casa Artom in the spring of 2026, one of his first calls was to Musci. Why don’t you join me? Brubaker asked. Stay tuned.

Ananda Mitra (MA ’87)

Professor of communication

& Kendall Hack (’11)

Head of customer success, Ceresa

A CLASS IN INDIA 15 years ago when Kendall Hack was an undergraduate — and the continuing support of Professor Ananda Mitra — shaped her career path in education and social change.

Hack made her first trip to India in 2010 for a summer study-abroad class taught by Mitra and got to know the people in Ladakh, an isolated region in the Himalayas. The next year, Hack and two other students who had taken Mitra’s course, Rachel Handel (’12) and Carrie Stokes Holst (’12), returned to Ladakh. With Mitra’s guidance, they researched the country’s education system, the particular challenges facing schools in Ladakh and how Wake Forest students could work with schools to improve outcomes.

Ananda Mitra with Kendall Hack (standing), Rachel Handel and Carrie Stokes Holst in 2011. Photo/Heather Evans Smith

Hack and Holst — by then both alumnae — returned again to Ladakh in 2012 to launch a service-learning project, Wake the Himalayas, for Wake Forest students to help students in Ladakh improve their English literacy skills. They designed the program to be a capstone project for students in Mitra’s study-abroad class.

That formative experience and continued encouragement from Mitra and his wife, Swati Basu, led to Hack’s next steps. She received a Fulbright Teaching Assistant Award to teach English in Malaysia and earned a master’s in public administration from Harvard’s John F. Kennedy School of Government and an MBA from The Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania.

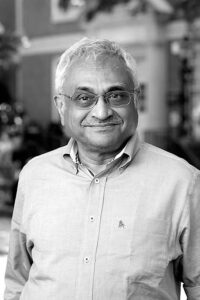

Mitra

Hack returned to India in 2019 to reconnect with the people she had met in Ladakh. Since then, she’s followed her passion to use education and innovation to bring about social change. Now living in Brooklyn, New York, she is the head of customer success at Ceresa, which provides leadership development and mentoring to underrepresented professionals to increase diversity in management positions.

Hack

Hack appreciates what she calls the “Ananda way.” “He always encouraged my questions and curiosity and new (way of) thinking without pushing a particular path or agenda. That led to authentic choices because I had that safe space to reflect and think and grapple with questions. His way is to draw it out of you, and then he is in your corner.”

Mitra, who grew up in Kolkata, uses the Indian word “ashram” — a small group of students and their teacher living and learning together — to describe his approach to mentoring. Hack, like other students during Mitra’s 30 years at Wake Forest, became part of the family with Mitra’s wife and son, Srijoy Basu Mitra. Mentoring “is a two-way street, and I include my wife in that,” Mitra says. “This is about the relationships that you build.”

As their relationship has evolved, Mitra and Hack both say their gratitude and respect for one another has grown. “I know that if I need something, there are a few people I can turn to, and one of them will always be Kendall,” Mitra says.

As their relationship has evolved, Mitra and Hack both say their gratitude and respect for one another has grown. “I know that if I need something, there are a few people I can turn to, and one of them will always be Kendall,” Mitra says.

Hack says that Mitra will remain a trusted adviser and friend. “I’ve learned you need different types of mentors to help you navigate life,” she says. “It means a lot to have someone who has known me for this long, who can draw on my values and dreams from over the years, who has seen me try new things, who has seen me question different paths, who has seen me through different highs and lows. That perspective is really rare and special.”