Matt Zakreski (’06) grew up in suburban New Jersey as the son of two child psychologists. He was tested for giftedness in second grade, but it was not until his sophomore year of high school that he was diagnosed with ADHD.

Matt Zakreski (’06) published “Neurodiversity Playbook” in late 2024. Photos courtesy of Zakreski unless otherwise noted

So, it was no surprise that, when he came to Wake Forest after falling in love with it on a college tour, Zakreski majored in both psychology and communication. After dipping his toe into being a political cartoonist, bartender, travel agent and even a stand-up comic, he returned to his roots, earning a Psy.D. in clinical psychology from Widener University in Pennsylvania. His research focused on social and emotional needs of gifted learners and branched out into best practices for neurodivergent people.

Zakreski has spent his career working to help neurodivergent children and teenagers better understand how their brains interact with societal structures. He’s passionate about reducing stigma around neurodiversity, instead promoting a culture of compassion and understanding to help people celebrate their unique brains. He has spread that message through more than 800 speeches worldwide, on National Public Radio, in The New York Times and through many podcasts.

His first book, “Neurodiversity Playbook: How Neurodivergent People Can Crack the Code of Living in a Neurotypical World,” was published in late 2024 and debuted as No. 1 on Amazon’s new releases list for gifted student education.

Kelly Greene (’91), managing editor of Wake Forest Magazine, caught up with Zakreski by Zoom at his home office in Roxbury township, New Jersey, to hear more about his work. On display behind his desk: The framed remains of his “WF” ultimate frisbee jersey, along with an Old Gold & Black sign. Here are excerpts from the conversation, edited for length and clarity.

Kelly Greene: Congratulations on your book! I love the way you started the acknowledgements: “Writing a book is HARD!” You provide so many great examples of the ways brains impact our thoughts, feelings and behavior. Do you have some favorite examples to share?

Matt Zakreski: When I think about how important it is to understand our brains, it’s primarily because, in the absence of other explanations, you default to the easiest explanation, which is always, “It’s my fault.” One fun piece of my neurodivergence is that I’m colorblind. But I didn’t know that colorblind was a thing until I got to middle school. So, I just thought I was dumb. Someone would say, “Hand me the blue crayon,” and I would look down at the box of 64 crayons and say, “Which one?” All the blues looked the same to me.

Arnold Palmer Residence Hall, where Zakreski lived his freshman year but could not study (now the Lam Museum of Anthropology). Photo by Ken Bennett

Then you learn what colorblindness is. Now, you have an explanation of the competing narrative for the same thing. But so many people are walking around with different brains not knowing that those brains are different. And it’s manifesting in behaviors and personality and likes and dislikes that are really impacting a lot of the things we do. So, if you don’t know your brain is different, you’re going to assume that you’re broken. I like to say that knowledge is empowerment, because I’m empowered by knowing that my brain is different. And that’s how we want to send kids forward.

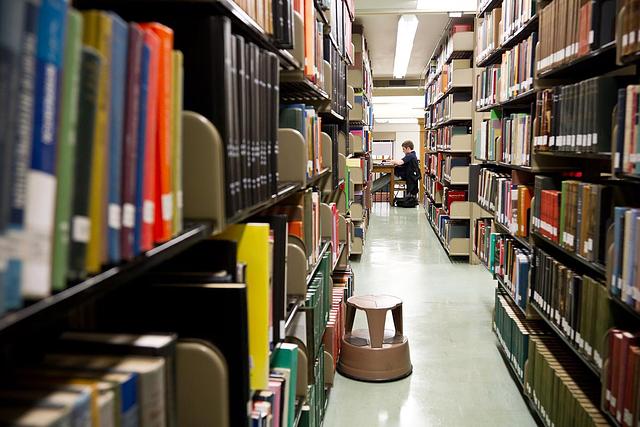

In college, I was in Palmer Hall my freshman year. I remember I would be trying to work in the common room with everybody else, and it would feel like things were vibrating. I was like, “Well, what are they talking about? Well, what is he doing? Is someone in the lounge?” I had to go to ZSR, to a nook on the fifth floor in the old building, because if there were no distractions, I could focus.

Knowing that those things were part of ADHD meant that I wasn’t just saying, “Oh, just work harder.” It was, “Oh, I know these are the things that my brain needs to be successful.”

Zakreski found an isolated spot where he could study without distractions in the stacks at Z. Smith Reynolds Library. Photo by Ken Bennett

KG: For people who might not be familiar with the terms, could you please walk us through what you mean when you talk about being neurodivergent or gifted?

MZ: Let’s start with neurodivergent. There are two kinds of brains in the world; 80% of people are neurotypical, which means their brain operates pretty much like we’d expect. … The world is largely built for and by those people. Neurodivergent brains are quantifiably different. The prefrontal cortex — that is the executive functioning part of our brain — develops a lot slower in neurodivergent people. For most neurotypical people, their prefrontal cortex develops somewhere between (ages) 20 and 25. For most neurodivergent people, it’s more like 28 to 35. We’re adding pretty much an extra decade onto that developmental process.

And when you think about late college, your early 20s, you really need your executive functioning skills to be successful. You rent your first apartment in downtown Charlotte, and then you get a letter from your landlord four months later like, “Hey, you haven’t paid rent at all.” You’re like, “What’s that? I knew I was supposed to do that thing, but where was I supposed to do it?” Things don’t connect. We can measure it. We can see it on fMRIs and say, “This part of the brain is bigger or smaller or more efficient or less efficient than what we’d expect a normal brain to do.”

Zakreski with friends at Commencement in 2006

KG: Is giftedness a subset of neurodivergence?

MZ: It is a relatively late addition to the neurodivergent world. For a long time, we thought that gifted was just smart. And famously when they looked at the outside of Einstein’s brain, they were like, “Oh, from the outside it doesn’t look that different.” It wasn’t much bigger than a normal brain. But now we have the technology to look inside the brain and see how it works. And we found that the brain has a certain number of neural connections. So, you’d expect somewhere between 70 and 100 million neural connections in a neurotypical brain. In gifted people, it’s more like 300 to 400 million. So, the brain is significantly more wired. And those connections mean, to use a very North Carolina reference, that brain’s not Business 40, it’s I-40.

A sign on Business 40, now called Salem Parkway. Photo by Ken Bennett

KG: For parents of a neurodivergent child who are faced with the choice of whether they would learn more, or be more comfortable, in a specialized class or as part of a “general” class, what’s your advice?

MZ: The good thing is, it’s not one size fits all. Increasingly what we’re seeing in schools is single subject acceleration rather than grade skip, because there’s so much social emotional variance in this population. So, to think about how the gifted brain develops, as a piece of neurodiversity, imagine that your brain has five developmental spheres: social, emotional, physical skills, intellectual skills and academic skills. And we know intellectual and academic skills are two different things.

It means that there’s far more doors open to you as a parent, as an advocate, and where you can work with your local community college or local university to get that acceleration. You need to meet your kid where they are in as many places as they are. So, if your kid is super advanced in math and science and coding, go to the places where they can take those classes. They’re not going to get anything from AP Computer Science Principles again in high school because they’ve already done that. But if they need to be with their same-age peers in English and history and gym and art, you absolutely can keep them there.

There’s no universe in which your math homework is more interesting than social media. ... So, we need to give your brain a fighting chance to overcome that temptation, lock in, do the work, so then you can step out of it on the other side knowing your math homework is done — and then go on TikTok.

It’s important to let your kids explore. Let them have unstructured play. But they’ll organically reach the point where we need something called MKO, or a more knowledgeable other. The idea is that everybody has organic limits to what they can do. And then, to take them to the next step, you need someone who knows more about it than you do. As parents, we serve them far better by being the guide on the side, not on the stage. Instead of saying, “Follow me,” it’s asking, “How can I help you along your journey?”

KG: You said a few minutes ago that one in five people are neurodivergent. As I was reading your book, I wondered if it might be even more.

MZ: It might be. In fact, the more we learn about it, I wouldn’t be surprised if that number creeps upward. Some people even call it one in three. So, what we’re doing here is we’re taking developmental rates, and we’re looking at, for instance, gifted is one in 50 kids and ADHD is more like one in 30, and autism is somewhere around one in 36. And dyslexia right now is one in 10 as the reading rates in this country crater. And so, you alchemize all those things and how kids can be multiply divergent. I wouldn’t be surprised at all if it changes, because we’re learning so much more about the brain.

Zakreski has given more than 800 speeches worldwide on the importance of better understanding neurodiversity.

And for years, psychology tried to do the medical model, and it was like you have ADHD, you have dyslexia, you have OCD. Those are separate, discrete things. But the brain is different. So, what we call things like ADHD is really a certain amount of executive dysfunction that interferes with learning. Well, that can come from giftedness and anxiety disorders and trauma and concussions and OCD. And I could keep going. We’re trying our best to sort of shift the language. We know we’re going to figure out the best terms for that as we move along, but we know your brain is different, so we’re going to learn more about what your specific flavor of that is.

You talk about your own moments growing up when you felt socially at a loss. Did that lead you specifically to working with gifted and neurodivergent children and teens?

I got identified as gifted in second grade, … and I was identified with ADHD in high school. I was in 10th grade. And it really did explain a lot, and it really took us a while to figure out what the right treatment for that was for me. What really helped was not thinking about, “ADHD is this, so I must be that, too.” It was thinking, “Who am I? What do I need?”

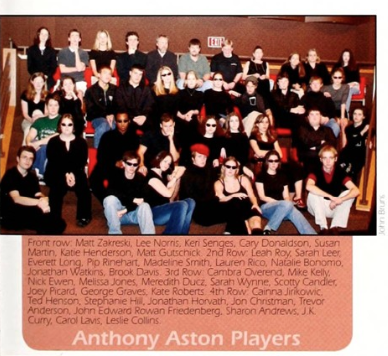

Zakreski was involved in theatre and ultimate frisbee, along with a fraternity and the Old Gold & Black, at Wake Forest. Photo from The Howler, 2005

My baseline functionality was really high. I often say to my clients, “Listen, you don’t have to change anything. You can keep white knuckling it through school, and you’ll probably get As and Bs. You’ll probably go to a good college, and you’ll probably be successful. My job is to help you work smarter, not harder.” So, asking that question, “How do we work smarter, not harder?” was really what personalized it for us. And what I really needed was a medication I could take when I needed to really lock in. Because when you’re taking high level classes and you have a social life and you’re in extracurriculars, and you’ve got an 80-minute window to do your homework, you can’t spend 20 minutes of it on AOL Instant Messenger.

As I say to my kids, “There’s no universe in which your math homework is more interesting than social media. That’s just not the case. So, we need to give your brain a fighting chance to overcome that temptation, lock in, do the work, so then you can step out of it on the other side knowing your math homework is done — and then go on TikTok.” It’s teaching the triage method of that. That was really the technique that worked better for us. We didn’t treat it as one size fits all. We really personalized it.

KG: You also talk about “cracking the code” of the neurotypical world. What are a few strategies that could help people start to do that?

MZ: We need to really focus more on giving kids the skills to be what we call pro-social. It’s the idea that my needs matter, and your needs matter. A lot of social skills programs train kids to be nice. But nice means that you’re really only focused on other people’s needs, not yourself, which means you’re easily walked over. It’s hard to get your needs met. And what ends up happening is you’re nice, nice, nice, nice until you get angry and blow up and everybody’s like, “Whoa, hold on. Where did all this rage come from?” And you’re like, “Well, people have been using me as a doormat for the last seven months.”

But then if you overcorrect the other direction, you’re too selfish. Then it’s hard to get things from the community. Nobody wants to work with you. So, teaching kids about collaborating, finding compromise, working together — there’s a resiliency that’s built into that that I think is so vital. Whether it’s someone in front of you in line at the Pit who got the last quesadilla, and you wanted that quesadilla, or you need to move somebody’s laundry out of the dryer, and are you allowed to do that? Those are the things that the more socially asynchronous you are, the more you can get stuck. So instead of assuming all kids will learn it, let’s make that programming intentional and give kids resources and conflict resolution and social collaboration. Not only are those vital skills right now for this phase of life, but it’s where the world is headed. Knowing stuff and knowing how to use it, manipulate it, synthesize it — that’s where the future is.

One of Zakreski's cartoons from the Old Gold & Black

KG: Going back to your time at Wake Forest, you were a political cartoonist for the Old Gold & Black. Do you have a favorite cartoon that you drew?

MZ: I love to draw cartoons. When I was in high school, I would just doodle caricatures of the teachers. And then our English teacher, who was also the editor of the school paper, said I should draw cartoons for the paper, and she gave me some local resources, one of which was the political cartoonist for our local paper, the Asbury Park Press in New Jersey. He happened to be Steve Breen, who actually won the Pulitzer. I learned a lot of the basics of setting up a joke and visual storytelling. It’s delightfully subversive — it’s telling a joke, but it’s telling a sneaky joke. You’d see the parts of campus that are rife for comedy. I mean, college is inherently a preposterous idea. You take thousands of kids from all over the world and put them in a place for four years and you say, “Go, we’ll give you food and a bed. And the rest of it you figure out,” and largely it works.

Zakreski with other student actors involved in theatre at Wake Forest

KG: You make a lot of pop culture references in your book. What’s your take on “Young Sheldon?”

MZ: Oh my gosh. For as many problems as I have with “Big Bang Theory,” “Young Sheldon” is kind of perfect. “Atypical” on Netflix is another really good one. For a lot of these kids, seeing shows where neurodivergence is presented in a way that’s affirming, not like a caricature, is very helpful. If you want people to understand something, if you really want it to land in their heart, it’s got to be something that’s personally meaningful. So, if I can make a connection, if I can make an analogy or a metaphor or a pop culture reference that drives that point home, then I’m increasing my audience’s ability to wrap their brains around what (are) some pretty ephemeral topics.

This is really hard to understand. I went to five years of grad school for this, right? And I’m still learning it every day. But if I can tell kids, your brain is like a 2027 Ferrari Testarossa with the brake system of the tricycle you used when you were five years old, that’s a good analogy for the gifted brain plus that poor prefrontal cortex, which is trying to regulate everything.

And you tell kids, “So it’s not your fault. Use this metaphor to understand yourself because neurodivergence is always context. It’s never an excuse. You’ve got a superpowered brain, you’ve got a Ferrari tester, but you don’t get to drive down I-40 and say, ‘Well, I have a superpowered car, so I’m allowed to speed.’ It means you have a responsibility to use that safely and effectively, and then when you can open it up once you get west of (town), just open her up and see what you can do.”

I’m a boots-on-the-ground guy. I don’t want to just sit in an office and dispatch people to do work. I maintain a full caseload, even though I’m traveling the country giving talks and writing another book. That ethos is what drew me to Wake in the first place. I got into a lot of other really strong schools, but Wake felt like the right fit for me because it was that combination of, “We want you to work hard, but we’re not just having you burn daylight. You’re working hard towards a purpose.” I was drawn to that model, which is why I am still a proud Deac all these years later, because it helped me grow up in a meaningful way.

It’s a powerful thing, and I use it to do my part to make the world a better place. I don’t want to just talk at you. I want to talk with you, because that’s how we’re going to make meaningful change. And I’m blessed that I get to do that every day.