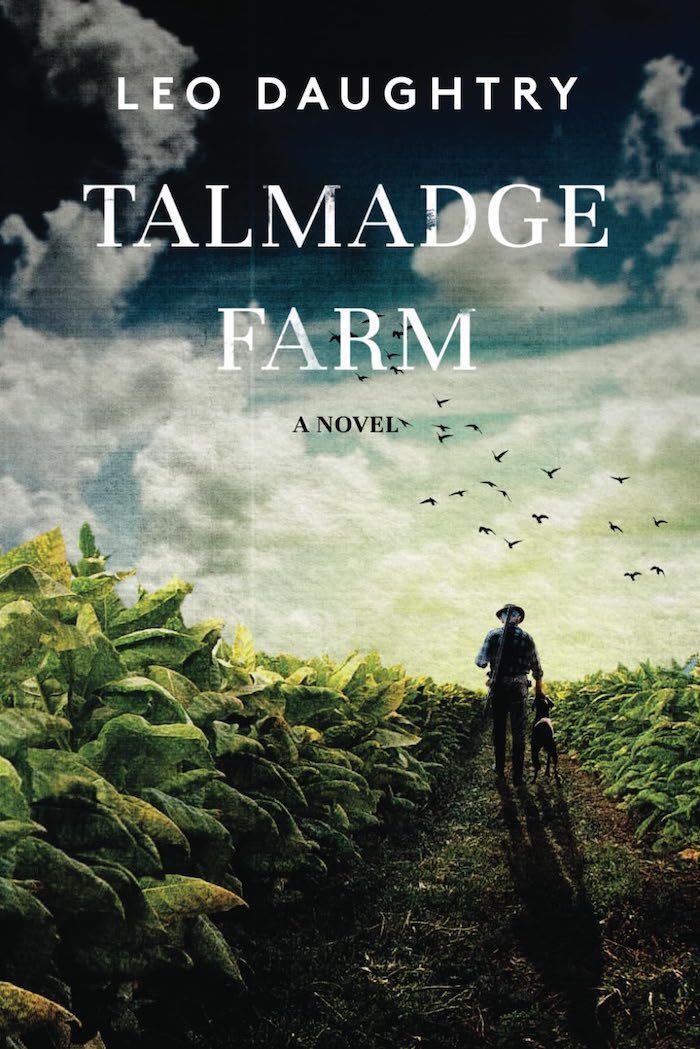

Leo Daughtry (’62, JD ’65) drew inspiration and many of the characters for his historical novel “Talmadge Farm” from his years growing up on a tobacco farm in eastern North Carolina in the 1950s.

Daughtry, 84, grew up in rural Sampson County, about an hour southeast of Raleigh, on a farm owned by his father. He weaves a story of the wealthy Talmadge family and two sharecropper families — one white, one Black — whose lives intertwine against the backdrop of socioeconomic and racial changes sweeping the South that upend their lives in different ways. He draws from boyhood memories of dove hunting, moonshiners, segregation, the backbreaking work of harvesting tobacco and sharecroppers scraping to survive at a time when tobacco was king in North Carolina.

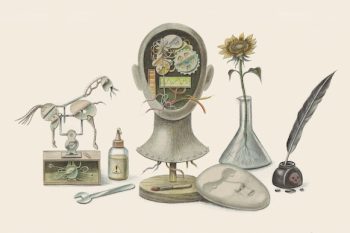

One reviewer described “Talmadge Farm” as a “stirring novel” with a “big, complicated portrait of family, place, race, class and greed.” The novel won first place in historical fiction in the 2025 Feathered Quill Book Awards and was named a finalist for the 2024 Goethe Book Awards for late historical fiction.

Daughtry and his wife, Helen, live in Smithfield, North Carolina. His granddaughters, Katherine Riley (’20) and Hannah Riley (’24), are also alumni.

Daughtry was a Judge Advocate General in the U.S. Air Force before founding law firm Daughtry, Woodard, Lawrence & Starling in Smithfield in 1969. He served in the North Carolina House and Senate for 28 years, and was House majority and minority leader, until retiring in 2017. A past member of the Alumni Council and School of Law Board of Visitors, he has endowed scholarships in the college and law school. The law school named its North Carolina Business Court courtroom in his honor in 2018. The North Carolina Bar Association established the N. Leo Daughtry Justice Fund in 2022.

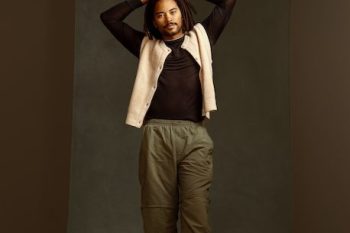

Kerry M. King (’85) of Wake Forest Magazine talked with Daughtry by Zoom at his office in Smithfield. Excerpts from their conversation have been edited for length and clarity.

Kerry King: Before we talk about “Talmadge Farm,” I’m curious to know why you came to Wake Forest and what it was like when you were a student.

Leo Daughtry: My brother-in-law (Bill Peak ’48, MD ’51) went to Wake Forest, and I followed Wake Forest sports — Dickie Hemric (’55) and players like that. There was a tournament called the Dixie Classic (held in Raleigh from 1949 to 1960) where the Big Four (Wake Forest, Duke, NC State and UNC-Chapel Hill) would play four other schools, and we would go to at least one game to see Wake Forest play.

Wake Forest had recently moved to Winston. Dr. (Harold) Tribble (LL.D. ’48, P ’55) was president. We had chapel on Tuesdays and Thursdays. There was no dancing on campus. If we had parties, we’d have them off campus. For football games, we all wore suits. If you were lucky enough to have a date, you always got her a mum or flower to wear.

Wake Forest was great for me. It allowed me to leave the tobacco farm and go to college and experience life in a different way than I had known before. And Wake Forest was very patient with me. I tried to be a good student, but I just didn’t have the background. It took me a while to get my bearings.

The Vietnam War was really becoming an issue. I went into the Air Force (after graduating from law school) and served in Turkey, assigned to NATO.

KK: Do you remember any particular professors, either in college or in law school?

LD: Dr. (John) Broderick in English, Dr. (Emmett Willard) Hamrick (P ’83) in religion, Dr. (David) Smiley (P ’74) in history and Dr. (Kenneth) Raynor (1914) in math. Dr. (Marcel) Delgado got me through Spanish. I didn’t have Dr. (Ed) Wilson (’43, P ’91, ’93) for a class, but I certainly knew and liked him. He was one of the finest guys and represented Wake Forest so well. I’ve gotten to know his son (Ed Wilson Jr. JD ’93), who is a judge.

In law school, Dr. (James) Webster (’49, JD ’51, P ’81), Dr. (Hugh) Divine, Dr. (Robert) Lee (JD 1928, P ’55, ’68), Dr. (Norman) Wiggins (’50, JD ’52). They were all good teachers.

KK: You had a long career as a lawyer and in the General Assembly. What inspired you to write “Talmadge Farm”?

LD: It had been germinating a long time. I wrote it from an outline I did when I was in the General Assembly. We’d have some debates that I didn’t have to be involved in, so I had some free time. I knew the characters I wanted in the book. The reason I chose the name Talmadge is because I didn’t know anybody named Talmadge so I could make him the bad guy. (Gordon Talmadge, a banker and the owner of Talmadge farm, is the book’s central character.) I would write the outline and then change it, and then write it and change it. I knew where I wanted to start and where I wanted to end.

Leo Daughtry ('62, JD '65), author of "Talmadge Farm"

KK: What were the major themes you wanted to write about?

LD: Well, sharecropping for one thing, and the 1950s. My most impressionable years were the late ’50s and early ’60s because I was a teenager. I saw all the changes that were beginning to occur in the South. I went to a very small country school, where half of the students at least were children of sharecroppers. I had Black sharecropper friends and white sharecropper friends. They had one thing in common. They were poor as church mice, and they had very little hope of getting ahead. Most of the kids that I knew wanted to get off the farm. Farms had gotten bigger, tobacco allotments had changed, and migrant workers were replacing the sharecroppers. And automation enabled farmers to be more efficient, and that just eliminated the sharecroppers.

(I also wanted to write) about change, how people have to change, and some people can change better than others. Gordon could not figure out how to change. He got left behind because of his inability to accept change.

KK: How much of the book draws from your experiences and people you knew growing up?

LD: Almost all of it. Gordon was invented; I had to have a villain. Everybody knows someone like Gordon. He had everything going for him, but he wasn’t very smart (and wouldn’t adapt to the changing South). Black people lived in a completely segregated environment then. I wanted to make all the women really strong (characters) because there were no women doctors or lawyers then.

KK: Alumni are sure to enjoy the tidbits you sprinkle in the book about Wake Forest, Winston-Salem, Old Salem and R.J. Reynolds. The book ends soon after one of the characters, David, graduates from Wake Forest. Was he based on you?

LD: No, but I really wanted David (the good son in the novel) to go to Wake Forest. I didn’t want the bad son (to go to Wake Forest). (One of the other characters) went to Bowman Gray (School of Medicine). And, I remember Christmas at Old Salem and those Moravian cookies.