I decided in 1975 to become a writer. This is a fact that will likely astonish anyone who read anything I wrote for decades beyond that, including, I am sure, many Wake Forest professors who were forced to churn through my practice attempts. For surely it is a truth that deciding to become a writer is only step one of many in the long journey from aspiration to accomplishment. I learned that on the way to publishing my first novel.

In the late summer of 1975, just as I was about to turn 14, my family moved to Oxford, England, where my father, a writer and theologian, was set to begin a fellowship at the University of Oxford’s Mansfield College. There was for me in that particular summer the very real angst around starting a new school, which was a rather potent cocktail of dread mixed with awkwardness.

All photos are courtesy of Carolyn Newton unless otherwise noted.

I was a confirmed bookworm, and perhaps in the hopes of putting a bit of British shine on my Kentucky accent, my parents gifted me a copy of “Jeeves in the Offing” by P.G. Wodehouse. I fell in love with his jaunty characters, sprightly wordsmithing and twisty plots involving English garden parties. Soon I was plowing my way through his vast collection of stories while contemplating how I might combine letters, words and punctuation in the kind of inspired order that makes readers feel something special.

My road from dreams to printed page, however, was long and fraught with detours. It was also nurtured by the benefit of experience and the guidance of mentors who offered encouragement, advice and soul-crushing honesty. My sojourn in Britain awakened the historian in me and honed my interest in the endless power struggles that shaped the world. I witnessed 1975 as a tumultuous year, and my preoccupation with Wodehouse’s comical bygone world quickly developed into a serious fascination with the lives of those who wielded less clout yet bore the outsized weight of consequences.

I returned to the United States eager to dive into different literary waters. I filled journals with heartfelt essays and poems, and I read James Baldwin, Zora Neale Hurston and Ralph Ellison. When I arrived at Wake Forest in the fall of 1979, I was eager and idealistic yet timid about committing my words to ideas. Four years under the tutelage of a brilliant cast of Wake Forest educators refined my naive wish list into a seasoned appreciation for skills and strategies, even if it was destined to be a rather long-range plan.

At Wake Forest, I learned to honor curiosity, to read for insight and understanding, to question assumptions and most of all, to contextualize knowledge with empathy. I carried my experiences with civil unrest and tensions from the Troubles conflict in Northern Ireland into Religion Professor Bill Angell’s (’41, P ’72) and Philosophy Professor Robert Helm’s (’39) Meaning and Value in Western Thought course, where the professors encouraged robust debate over values and ethics.

A course on early English history was notable for the way History Professor Cyclone Covey (P ’72, ’75, ’85) trained us to craft our conclusions with brisk specificity. His buzzword was brevity, and his final exam was daunting. Imagine 25 essay questions with instructions to answer each using only one fully informed and succinct sentence. No beating around the bush, hoping to hit on a kernel of truth. You either knew the answer, or you didn’t. He certainly taught me about making a cogent argument.

German Professor Tim Sellner (P ’96, ’02) emboldened my inner Germanophile in his literature class, where I was the only freshman among some very talented upperclass students. His enthusiasm and patience was sorely tested by my sluggish progress with Goethe’s “Die Leiden des Jungen Werthers.” Despite being utterly exhausted from the effort and logging hours on the Johnson Hall payphone in tearful chats with my father (who spoke German like a champ), I emerged with an appreciation for the beauty and cadence of the German language — die deutsche Sprache — a skill that would serve me well as an author.

My Wake Forest career was capped by a senior history seminar with the wonderful Dean Tom Mullen (P ’85, ’87), who led a small group of intrepid history scholars in a study of Otto von Bismarck and the makings of the modern German state. Although I had a pesky habit of misspelling Bismarck’s name, my experience with Professor Mullen’s robust discussions influenced my master’s thesis on the failures of First World War diplomacy and global repercussions in the 20th century.

All these gifts I carried with me beyond Wake Forest. I kept up my writing and published a few articles here and there. Marriage, motherhood and career were the priorities that governed days cluttered with joy, challenges and demands — hardly the recipe for unbridled creativity. I dove into teaching history, drawing from the pedagogical inspiration of my Deacon days and concentrating on little known stories that define the struggles and challenges of being human in a power-hungry world. And I dreamed year after year of writing a novel.

Heeding Clarissa Pinkola Estés’ admonition that art is not meant to be created in stolen moments, I forged my path. I committed to prioritizing writing time, generally late at night when the house was quiet and caffeine-fueled inspiration was uninterrupted. My full-circle moment arrived with the serendipitous discovery of the “Wolfskinder” story, a tale of German children torn from their families when the Soviet army invaded East Prussia in 1945. Tens of thousands of children fled into the forest, some as young as 3. They were forced to reckon on their own with a cruel world where they were seen as enemy combatants. Those who survived languished for decades behind the Iron Curtain.

I scoured international databases for information and found diaries and written accounts, all in German and most hidden for years from prying authoritarian eyes. I collected interviews with survivors and family members, and I developed a cadre of authors, academics and researchers who generously shared their expertise to broaden my understanding of the traumatic lives these survivors had led.

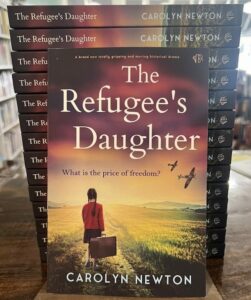

With my manuscript complete, I began the daunting task of selling my work, a process that requires more than a dollop of steely determination and a very thick skin. I was fortunate to secure the support of a London-based agent who remains a wonderful advocate, but the story was a tough sell. Publishers had to be convinced that a Cold War narrative set in the Baltics would attract attention.

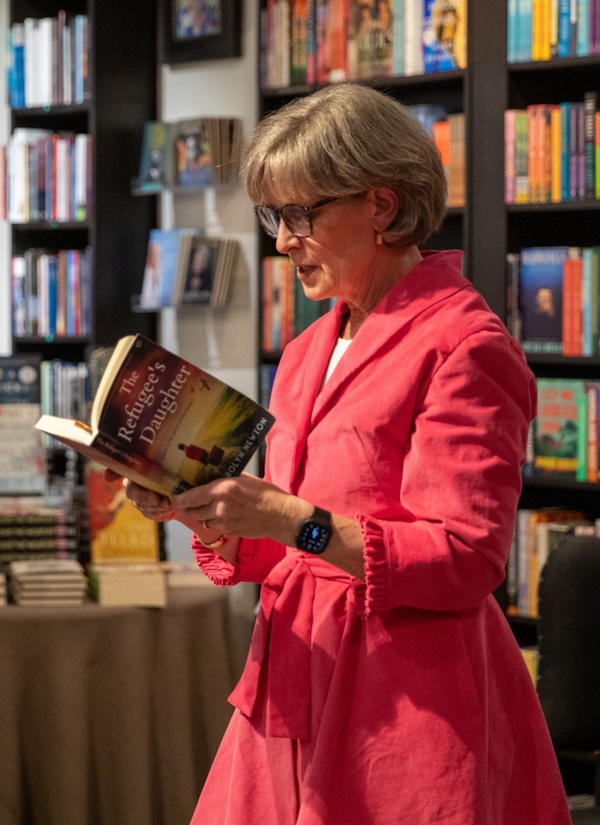

Finally, in a happy ending decades in the making, “The Refugee’s Daughter” was released to positive reviews in November, and just to put some icing on this literary cake, my next novel, “Songs of the Dead Road,” is under contract with a launch date in February.

A childhood spark was nurtured into a scholar’s dream at Wake Forest and tended over a full and curious life. I haven’t binge-watched a show in years, and I can’t promise that all the chores are done, but the tradeoff in creative expression is absolutely worth it. It’s what P.G. Wodehouse would call a “high spot.” Cheers indeed.

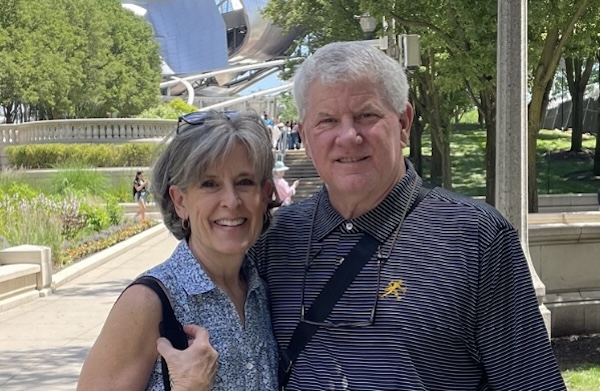

Carolyn Newton (‘83) is an author, historian and educator. Her first novel, “The Refugee’s Daughter,” was published by Bloodhound Books in November, and her second novel, “Songs of the Dead Road,” is scheduled for release next February. She and her husband, Warren Newton (‘81), live on a lake in Seneca, South Carolina. They have three children, eight grandchildren and two rescue dogs.