Back when women rarely worked in the realms of math and science, Barbara Broadway Gormsen (’59) fearlessly did research for NASA along with the women featured in the movie “Hidden Figures.”

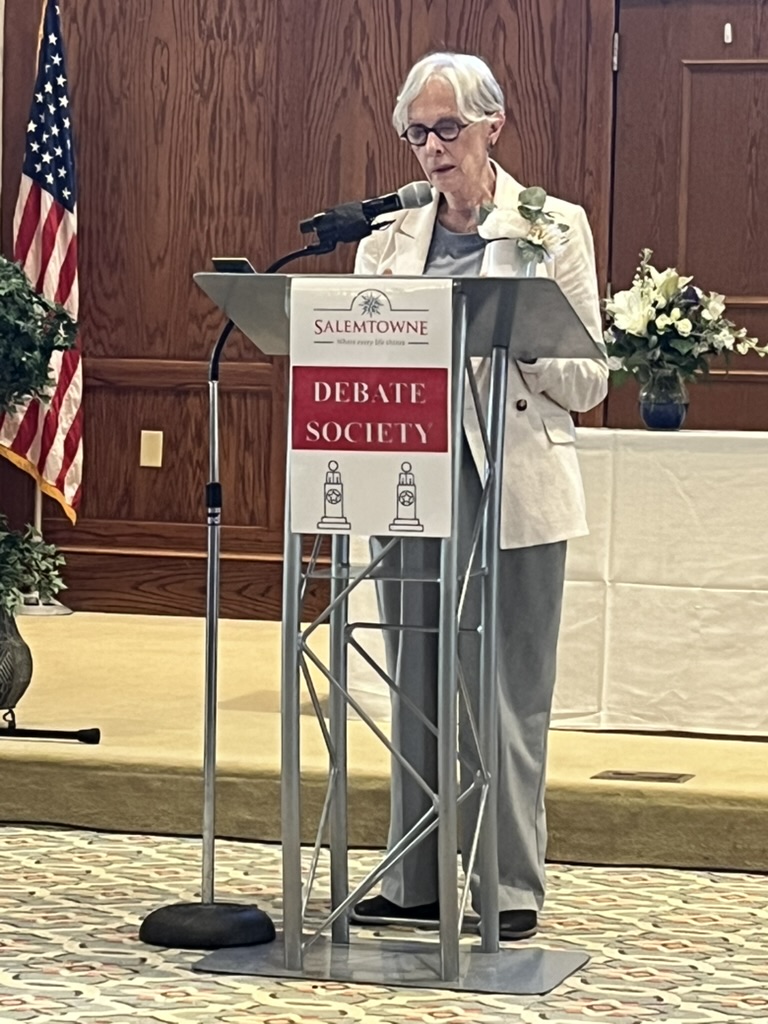

So, how did she feel while standing at a podium on a recent Friday afternoon, preparing to make the opening statement in a debate tournament?

“I was scared to death,” she says.

Gormsen is part of a fledgling debate society at Salemtowne, a retirement community three miles from Wake Forest’s Reynolda campus. She was arguing that college athletes should be paid for their “Name, Image and Likeness,” or NIL. The NCAA introduced rules in 2021 that let college athletes to monetize their NIL rights.

But this was a tough crowd to persuade with a “pro-NIL” argument — a room packed with retired professionals and educators, many of whom had taught at Wake Forest, graduated from Wake Forest, or have had children or grandchildren do so.

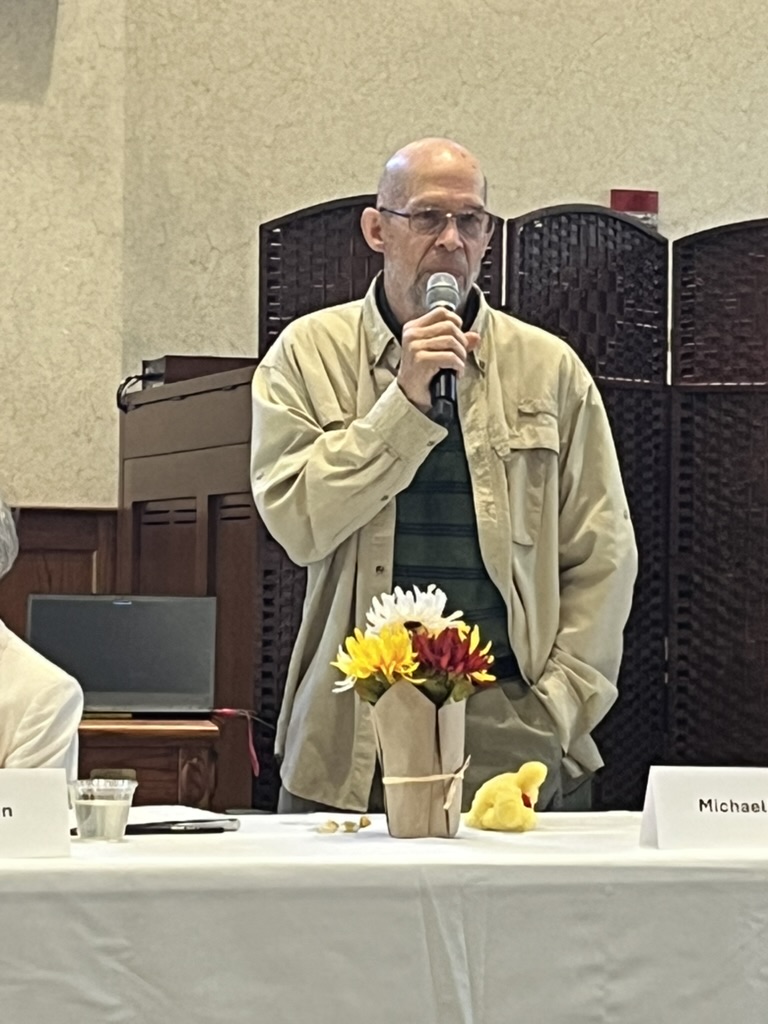

It didn’t help that the opposing team brought a fun prop: Michael Boing, who spent two years at Wake Forest as a Carswell Scholar in the late ’60s before graduating from NC State University, held up a stuffed duck while talking about the $1 billion gift Nike Inc. co-founder Phil Knight made to the University of Oregon’s NIL program, saying: “If it walks like a duck and talks like a duck. …”

Gormsen’s team had a visual aid as well: Fred Kahl, professor emeritus of cardiovascular medicine at Wake Forest School of Medicine, placed a basketball signed by famous Demon Deacon players — who did just fine in the era before NIL — on her team’s table.

But in this debate society, you don’t get to choose which side you wind up defending, so Gormsen and her teammates gave it the college try, even though she confessed afterward that she agreed with the opposition. In fact, she used to be such a devoted men’s basketball fan that she took vacation days to watch the ACC tournament and March Madness. Now, she says with a sigh, “It’s just like watching the pros. They just dribble and shoot.”

Cole Wolfe, a junior and Presidential Scholar at Wake Forest as well as three-time Oklahoma high school debate champion, worked with the retirees-turned-debaters before their most recent tournament. “You’d think that coaching octogenarians is different than coaching high schoolers, but a lot of the basics remain the same,” he says. “The only things that really changed were speed and life experience — which is invaluable to leverage in debates like this.”

Wolfe was awed by the debaters’ knowledge of individual Wake Forest basketball players. “They knew them,” he says. “And it’s people that I’ve never even heard of, because this was their stomping ground a decade before I was even born.”

The NIL debate was Salemtowne’s third go-round in the past two years. The society started with a lighthearted look at happiness and then moved on to book banning before tackling college sports.

When Wake Forest’s student debate team won the national championship in intercollegiate debating in 2023, Stormie Bruce, Salemtowne’s director of life enrichment, was inspired. She remembered resident Perry Craven sharing that she had been a high school debater in southwestern Pennsylvania. “It was before Title IX,” Craven says. “I was definitely not a cheerleader, but I could do debate.” Craven would practice speeches 25 times in a row — and her school won the state championship.

Bruce, thinking about the many retired educators, doctors and other professionals living at Salemtowne, decided to see if she could drum up interest in starting a debate league for people like Craven, who wanted the experience again, along with those who had never had the opportunity.

Collegiate literary societies once trained generations of orators, so starting a debate group didn’t seem like much of a stretch as an activity for a retirement community already steeped in book clubs and trivia challenges. “I posted that article (about Wake Forest winning the National Debate Tournament) on our internal website and said, ‘Debate, anybody?’” Bruce says.

Next, she had lunch with Allan Louden, who retired from Wake Forest after 45 years as a professor, including three decades as director of debate. A member of Salemtowne’s “Towne Club,” for people who plan to move to the community down the road, he seized on Bruce’s idea, seeing it as a way to engage people who preferred the “life of the mind” to arts and crafts. Louden quickly tapped Jarrod Atchison (’01, MA ’03), the John Kevin Medica Director of Debate and professor of communication, for help.

“Salemtowne has this subset of civically engaged, caring people who were also intrigued by the competition,” Louden says. “Almost everyone here has Wake ties. They worked there, or their kids or grandkids went there.”

To familiarize the retirees with the way debate works, Atchison recruited two current students on the debate team to demonstrate. Residents came up with a debate topic on the fly — whether transgender athletes should be able to compete against cisgender athletes — and the students, after a few minutes of research on their phones, got to it.

Wake Debate has a tradition of doing outreach, Atchison notes. The team has debated against incarcerated teams in competitions organized by the non-profit National Prison Debate League. Students also travel to New York during spring break to coach high schoolers in the New York City Urban Debate League.

The retirees weren’t exactly hooked. Only a handful turned up for the first few organizational meetings, despite having experienced professors and students on hand to help them get comfortable framing their arguments and practicing speeches.

It turns out that the terror induced in many people by public speaking doesn’t necessarily wane with experience. “It was kind of a struggle at the onset, because people were fearful,” Bruce says.

Still, the faithful six to 10 who continued to show up decided to go for it, focusing on a lighthearted question for their first attempt: “Is an increase in knowledge an increase in happiness?” It was the topic debated on April 23, 1875, by Wake Forest’s Philomathesian Literary Society. (Louden and Atchison published a book titled, “Milestones: Defining Lists of Wake Forest Debate, 1835-2024,” in December, so they had a list of happiness topics debated through the years at their fingertips.)

The format was “Lafayette style,” originally designed for tournaments sponsored by the French Embassy: Opening statements followed by cross-examination, closing statements and 15 to 20 minutes for audience questions and comments. A pro/con vote is taken before the debate begins and after it ends to decide the winner. A few more folks joined for the book banning debate, and now the society continues to gather members.

One faithful fan is Martha Swain Wood (’65), a prominent woman on Wake Forest’s debate team. She attended debate workshops at Wake Forest starting in high school (staying in Bostwick dorm, with no air conditioning). “I loved it, and I did pretty well,” she recalls. “I said, ‘If I get into Wake Forest, I’m going to join the debate team.’ … It was the best thing I did at Wake Forest.”

She got in, and did just that, remembering the team as being “like a family. We would all pile into one station wagon, with all our luggage,” and Franklin R. Shirley, her longtime coach, would drive them to tournaments around the country. “He would always make sure we had one meal in a nice restaurant,” she says. “In New York, we would always go to Mamma Leone’s and see a play. He thought that was part of our education.”

Following in Shirley’s footsteps, Wood went on to be elected as Winston-Salem’s mayor for two terms. Although she lives at Salemtowne, she has demurred from joining the internal debate league, focusing instead on her work as co-chair of legislative affairs for the North Carolina Continuing Care Residents Association, lobbying for a bill in the state legislature to strengthen financial oversight of retirement communities by state regulators.

Now, Atchison is hoping to spread the idea of debate as part of lifelong learning, possibly through the University and retirement communities around the country (some with ties to former Wake Forest debaters). He sees potential for “debate in a box,” with Wake Debate equipping new teams with how-to DVDs and setting up tournaments online, with the goal of hosting a live tournament for the finalists at Wake Forest.

The Salemtowne society’s growth and learning come through in the work of Naz Sayari Marcum, a graduate student in Wake Forest’s documentary filmmaking program who is chronicling their lives and experience as her thesis. “Debate really gives them a purpose, and I think we all need that,” she says. “That’s why I was drawn to this. Aging is a crucial part in our lives. … Some people like to have a challenge in their lives, and they want to stay sharp. This is what they needed.”

In interviews for her proof-of-concept reel, the social and intellectual benefits come up repeatedly. “We pick a topic, and you have to research it,” Barbara Gormsen says. “And I haven’t really done that since I retired — and that was a few years ago.”

Fred Kahl has appreciated the broader exposure to other points of view: “It’s not so much that five or 10 minutes where you are actually doing the debate, but it’s all the research you do ahead of time, and you can learn all the opinions.”

Adds Louden: “Those people who understand others and are more tolerant and can work with folks are those who have had more experience. They’ve been out and done more things. They’ve encountered more points of view. Debate forces that — markedly forces that interaction of ideas that inherently makes you more tolerant, because you have a larger understanding.”