Christian Waugh (P ’27)

Professor of Psychology

Psychology Professor Christian Waugh (P ’27) specializes in research about cultivating positive emotions to regulate stress, temporal dynamics of emotion and the psychophysiology of emotions and personality. While his focus isn’t specifically on the psychological and physiological benefits of being outdoors, Waugh discussed the relevant academic work in his field — and his excitement over an intriguing recent experiment.

His personal interest in seeking time outdoors is “100%” — from camping to hiking to relocating to a home near a greenway where he can walk and bike.

His favorite theory about how humans innately are attracted to nature – the biophilia hypothesis

As a species we’ve evolved over hundreds of thousands or millions of years, so our brain comes to expect certain things from our evolutionary path. … One of the things it expects is to be in nature, because that’s where we were for 99.9% of our evolution. We were out in nature. We were out in the jungles, in the savanna and the plains. That is where we got our resources. If you wanted food, nature is what had the food. If you wanted water, nature was what had water. … Nature held all the resources that we needed to survive and thrive, and our brain remembers that from this ancient time so that when we go out in nature, it sort of harkens back to this ancient time: This is what led me to survive and live and be who I was supposed to be. I love that idea. …

A second area of research, known as Attention Restoration Theory or Cognitive Restoration Theory

When we are in our built environments, … they’re designed to be functional for the most part. Some obviously are aesthetic, and we appreciate the aesthetic ones, but most of them are just designed to be functional. They have lots of moving parts. They have lots of things that are designed to do stuff.

Right now, in my office, in my house, there’s stuff everywhere. Everywhere. There are different clashing colors. There are clashing shapes and forms. There are things moving over here. There’s light coming from over there. There’s lots of different stuff happening, which is attentionally exhausting.

We go out in nature — that goes away. (Nature is) attentionally relaxing. But what’s interesting is, it’s not less engaging. It’s still engaging our attention, because you’re out in the woods, in the forest, and it’s beautiful and aesthetic, but it’s not as exhausting to process. It’s actually a short cousin of a theory (relating) to aesthetics and beauty overall, which is basically anything we find aesthetically pleasing and beautiful, it’s because our brain processes it very easily. This is why we love symmetry. This is why we love some paintings. We just don’t know why we get it and love it, but we just do because it’s easy to see it.

What he calls a recent, “blossoming” theory about the benefits of nature

We know that plants give off these organic compounds, and they’re called biogenic volatile organic compounds, BVOCs. There are lots of different ones. One is called terpene, and it’s a compound emitted by plants for lots of different reasons, one of which is to defend themselves against predation. And there’s a theory that these terpenes when breathed in directly affect the physiology of humans. Isn’t that amazing?

They have a 2025 study … showing that you take people out into the forest, and you put a helmet on all of them with a filter on it. Everybody has the same filter, sitting out there in the forest. But you activate the filter on some and not on others so that some terpenes get filtered out and some they allow in. So, it’s controlled as much as possible. And what they found is (people) who are allowed to have those terpenes in show slight decreases in these immunological factors, these inflammatory factors, that are indicative of better health and less stress. … So, it’s very hot off the press. … If that (theory) turns out to be valid, that will literally mean … plants are communicating to us chemicals that regulate our own physiology through the air, which is amazing.

Finding time for nature and experiencing the power of awe

To reiterate what we’ve touched on, any little bit of nature helps, but it’s best when you’re fully immersed. But that doesn’t mean you shouldn’t do the little things, like having plants in your office or your room … or watching a nature film. Those things matter. It’s just that they are not going to be as powerful as being in nature and invoking all the senses. Urban green space is good. Wild nature is better.

One thing we didn’t talk about is awe, an amazing emotion with a lot of positive psychological benefits but in a funky way, which is that it basically makes you feel small. It reduces your self-consciousness, which recalibrates that you are just a part of the world, not the world itself. You’re just … a teeny, little part of the world, which is humbling and reduces your self-consciousness and has weird psychological benefits because of that. (Awe) can also be terrifying, so it’s not like it’s a purely positive emotion. There’s some fear in there, too. You get awe from seeing a mountainous landscape as well as a tornado or thunderstorm coming at you.

Amanda Vincent

Associate Professor of French Studies

Associate Professor Amanda Vincent has combined her interests in French culture and landscape architecture into her research for nearly two decades, starting with a 2007 journal article about a Parisian park whose creators blended the ruins of old wine warehouses with contemporary features, and culminating in her 2023 book, “Constructing Gardens, Cultivating the City: Paris’s New Parks, 1977-1995.”

But it wasn’t until 2019, when she worked with a horticultural high school in Nantes, France, that Vincent was truly bit by the gardening bug. She watched professors guide teams of students who, over two years, created their own landscape plans for sections of the school’s garden — and then put those plans into practice.

“It was a magical experience,” she says. “I came home motivated to have more of my own personal gardening practice and to see how it could become part of the classroom and pedagogy, thinking more about how gardening could be tied into a liberal arts education.”

Digging in

Vincent spent a lot of time digging in the dirt in 2020 and also developed a first year seminar called “Gardening on Paper and in Practice” that she taught in the spring semester of 2021 — the perfect time to get students outside for class as much as possible — and again earlier this year. Students read works by distinguished authors about gardening as a practice of care, cultural practice, healing practice, sustainability practice and as political engagement. They look at the spiritual aspects as well through excerpts from “Soil and Sacrament: A Spiritual Memoir of Food and Faith,” by Fred Bahnson, former director of the Food, Health & Ecological Well-Being initiative in the School of Divinity.

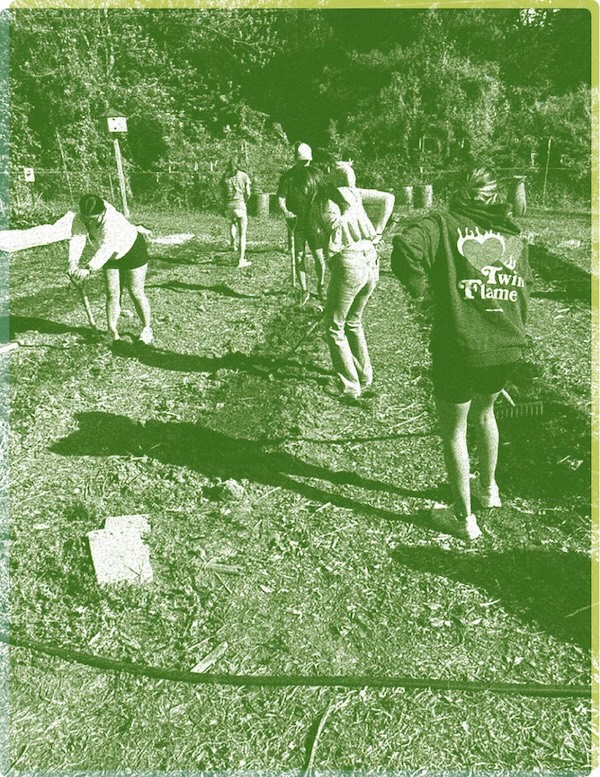

As the semester progresses and the weather warms up, they meet more often in the Campus Garden, relating the definition of gardening’s purpose that they develop in class to their own experiences. On a sunny Friday morning in April, Vincent and a Campus Garden intern show 11 students how to use garden forks, scuffle hoes, spades and wheelbarrows to prepare beds for tomato planting that contributes to research led by Gloria Muday, Charles M. Allen Professor of Biology and director of the Center for Molecular Signaling.

“This is a demonstration of regenerative agriculture techniques with tools you would see in gardens in France,” Vincent explains. “It’s supposed to be no till. The soil has layers. We’re moving the top layer a little bit, breaking up the soil, but not turning it over.”

As an aside, Vincent takes a few minutes to show the students a clover plant’s lengthy roots and to explain that the plant “can take nitrogen from the air and transform it into nitrogen in the soil that plants can use.” It ties back to Bahnson’s writing about his attraction “to the fervent and secret work that goes on beneath the surface.”

Know-how plus ‘know-knowledge’

“I like the theoretical reading about, ‘What does it all mean?’ I want the students to think about what motivates them and if it has meaning,” Vincent says. “But physically doing it is a different way of learning. Using a scuffle hoe is a know-how, not a ‘know-knowledge.’ You don’t think about all the different steps before you put the plants in the ground.”

Associate Professor Amanda Vincent’s students spend time in the Campus Garden learning about, and practicing, regenerative agriculture techniques.

The class culminates with an “unessay,” meaning the students choose the format, often an oral presentation, newspaper article, model or poster. They create and present a garden design and cultivation strategy that incorporates their readings, research and gardening experience. Vincent hosts a presentation day in lieu of a final exam. The students get treated to muffins Vincent bakes from scratch using carrots they harvested together.

Harrison Carl (’28) kicks things off with a quiz on plants and herbs with “deep connections to healing,” inspired by the gardening he did growing up with his grandfather. (They mainly planted cherry tomatoes and basil.) “I wanted to show how common plants and herbs have deep connections to healing, and often we don’t realize it,” he says. “And gardens don’t just heal individuals, but communities. They root us in cultural traditions, encourage care and create spaces of creativity and connection.”

Garden prescription

Gissel Tranquilino (’28) designed a therapeutic healing garden for a children’s hospital, because “healing gardens use nature’s calming and restorative effects to aid with recovery, reducing stress and promoting overall well-being,” she says.

“I also thought about putting myself in the shoes of maybe a 5-year-old child going into this hospital. … My research showed that (a healing garden could lead to) shorter stays, less need for medication and treatment, and it could also be a positive distraction,” she says.

Her design focuses on “accessibility; smooth, wide paths; a lot of areas for walking around; and also different kinds of seating, especially those with armrests.” For activities, she envisions “a vegetable and fruit garden that would allow kids to plant seeds, learn how they grow and then eat the plants and harvest them,” she says. “And then I thought about a garden passport, so kids could go around different areas of the garden, take turns doing … jobs like planting, watering, digging, and then for each activity … they could get a little stamp.”

Designed to de-stress, and contemplate

As a member of the men’s tennis team, Andrew Delgado (’28) says he started out “thinking about gardening as a tool for recovery and performance, to just be ready for the next game. But then I realized I was stuck in a high-performance mindset. So, I shifted the focus,” he says.

“I needed it to be quiet, calming with herbs like lavender or mint, a place to sit and hands-on planting beds,” he says. “You’re tending to yourself through tending to your plants.”

Peter Cory (’28) researched zen gardening as a mindfulness practice, with every element in his garden design holding intention, according to the booklet he created as his final project. “My garden design begins with a three-foot tall fence/wall. Within the wall I plan to have stones that fill the interior to give the deserved protection to the space,” it reads. “The clustered stones represent the flow of knowledge and ideas within my close relationships, while the upright pillar-like stone symbolizes my journey of personal growth.

“I placed a boulder towards the upper-right corner as an emphasis on staying grounded even when you might feel off balance,” it continues. “The ripple patterns, although temporarily circles, are transformative in their nature and signify impermanence, inviting contemplation and mindfulness.”

As does Vincent’s seminar.

Katherine Whitley

Staff psychologist and outreach coordinator at the University Counseling Center

Sometimes students get so overwhelmed by their academic workload that they forget going for a walk or simply sitting under a tree might help them feel better.

That’s where Katherine Whitley comes in. As a staff psychologist and outreach coordinator at the University Counseling Center, as well as a fan of hikes with friends, one of her favorite strategies to foster mindfulness, reduce stress and encourage self-care is getting students to spend time outside.

The need to slow down

There’s a big culture of productivity, especially at Wake Forest and just broadly socially. People are very much working towards some kind of outcome or output to grades or achievements. …

A lot of what we’re talking about with a connection to nature has to do with mindfulness. I think sometimes it’s a very difficult thing for many people, especially students, to be on board with because so much is being asked of them. Why would we slow down when we feel like we need to speed up?

Students of the current generation do utilize their phones and their screens a lot. … It impacts their mental health in a lot of different ways. To be really driven has lots of pros, but I think the cons of that are never feeling like you can slow down, never feeling like you can make a mistake.

Leaves floating away

There are even mindfulness activities that are based on nature. One of the ones I use is called “Leaves on a Stream.” It’s building up our ability to be aware of our thoughts and feelings without engaging with them or placing some kind of judgment on them. It’s an imagery exercise where you ask the person to imagine … they’re sitting beside a gently flowing stream. I’ll ask them to paint the picture for themselves: What season is it? What are you seeing? What are you smelling? What are you hearing? But then you take a look down at the stream and the water, you notice there are leaves floating along the stream.

And then we practice this ability to take each and any thought or feeling that enters our mind and place it on the leaf and allow it to float by. That’s called the skill of diffusion. How can we get some space from our thoughts? And then we usually process that afterwards and talk a little bit more about: How did it feel? Did you get some space from your thoughts? Were you able to have a different perspective on things?

(The goal is to be able to) name that that’s something I’m thinking or feeling, but it doesn’t have to become all-consuming in this moment. I’m not my thoughts and feelings, but I can be a vessel for them to flow through.

“Habit stacking”

We often offer (ways to get outside): doing your work outdoors, meeting up with your friends and sitting outside, taking a walk utilizing the Reynolda trails and even trying to get off campus for students that do have that resource.

We can sometimes utilize habit stacking, so connecting it with something that they already enjoy doing. One person may really enjoy reading or listening to an audio book or a podcast or music or talking to a friend or family member that’s here. So, how can we pair that with being outdoors? Can we go pick a spot outside or go for a walk?

I try to mirror that for the students, talking about how even when you are an adult and you have a 9-to-5 job, we still need to take breaks throughout the day. … I really enjoy walking the trail that connects the campus to Reynolda. … I remember when I first came here thinking, “This is an amazing place to work just because it’s very beautiful.”

There’s a big culture of productivity, especially at Wake Forest and just broadly socially. … Why would we slow down when we feel like we need to speed up?

We want to get to the point where we are engaging with (nature) presently, in the moment. I always try to give this psychoeducation of, “This is the reason why we’re talking about this. We’re trying to build up your ability to be mindful, which is to be present in the moment, utilizing your awareness of your thoughts and feelings, but without judgment or without trying to hurry the experience along. Sometimes being out in nature is a really positive way to do that because when you’re present with whatever nature has going on in the moment, you can really tap into your different senses.”

There’s a big culture of productivity, especially at Wake Forest and just broadly socially. … Why would we slow down when we feel like we need to speed up?

And some of the coping skills that we often provide students and walk them through have to do with our five senses. It can be a great skill for reducing anxiety or panic, grounding ourselves when we’re feeling overwhelmed. So sometimes we’ll utilize those examples that tie into nature.

Plant parallels

Whitley’s role includes outreach, often through pop-up events around campus. Nature has found its way into that work as well:

We had a great idea from our students for succulent-planting events. We talked about caring for your plant; you would care for yourself just like your plant. We tried to make it a parallel process: Make sure your plant is getting sun; make sure you get outside. Are you drinking enough water? Are we a little bit withered right now? Are we a little bit burned out with everything going on with schoolwork and social life? So, it was very fun to have the students get their hands dirty and take the succulents, put them in a pot, decorate the pot and then take it home with them.

Lucas Johnston (’98)

Professor of Religion and Environment

Before Lucas Johnston (’98) went to graduate school and eventually made his way to the Department for the Study of Religions at his alma mater, he remembers being a student at Wake Forest without “a good understanding” of the habitat around him. Work experiences changed him.

He traces what he calls his environmental consciousness to the early days after he graduated from college. He taught at a religious high school in the U.S. Virgin Islands and began to pay attention to coral reef damage and environmental degradation. “For the first time I started wondering about the connection between religion and environmental issues,” he says. His perspective expanded after he worked in Wyoming on a campaign to limit snowmobiling in Yellowstone National Park because of deleterious effects of the noise on wildlife.

What role have religions played in humans’ relationship with nature? As he began his graduate studies, he expected to find that most religions have espoused an emphasis on the “vertical relationship” with spirit but not on the horizontal relationship with everything else besides human beings. He found that, no, that’s not the entire story. There are religious traditions with a strong reverence for nature or respect for nature as an authority.

Johnston seeks to have his students think about where religion comes from and its connections to evolutionary psychology and the cognitive science of religion. He wants students to develop critical thinking skills to help them sort through the vast number of narratives available in this modern digital world: “What I ask them to do is hold these up against each other and say, ‘Look, so these are competing ideas about environmentalism (for example). Which one speaks to you, and what are the sources of authority these people are calling on?’”

Nature as a spiritual assignment

(Being outside in nature) is something I try to convey because I think the students here are very ambitious and driven. If you don’t force them to, they don’t go take time for themselves very well.

On the one hand, I think it is a subversive suggestion that they go outside for a little while and put down their phones and their books. In some classes I’ve even assigned that as homework once a week: Go to the same place over the course of the semester and sit there without your phone or your computer for 15 minutes or 20 minutes and just record what you see.

Most of them are, like, “Oh, there’s a squirrel, and then there are trees and birds.” But even that (is) just noticing things. There’s an intentional element to where you cast your attention. That piece of it is important, but … one of the things I try to talk about is that just being outside can be a source of spiritual renewal and growth.

Our place in the universe

Getting outside is literal and metaphorical. Our classes are supposed to get people out of their comfort zones to some extent (and) expose them to new knowledge. But sometimes one of the best and easiest ways to do that isn’t in a book. It’s physical — recognizing what your body is doing that’s different when it’s sitting under a tree and sitting in a chair. You are maybe sore after you sit under a tree, but it’s not the same thing as being sore from sitting in a chair and studying the whole time. Just recognizing. Being an embodied human being. Just being in the world instead of on it.

That’s kind of the distillation of it — imagining yourself just like everything else as subject to the laws of life. You ignore those at your peril, and we can dress it up however we want. We can put social causes or economic issues or whatever we want, but at bottom, that’s what it’s really about: who we are and what’s our place in the universe or in the world. …

We can book it to death. We can find a thousand different perspectives on why it’s important to go outside or different religious people who said, “Go outside.” (He gives St. Francis as an example.) So, thinking about those things, there are ways to cast it through our religious lenses, but fundamentally it’s a human experience of being in a world of (beings), only some of whom are human.

Megan Bennett Irby (’06, MS ’12)

Assistant Professor of Health & Exercise Science

Megan Bennett Irby studies chronic health conditions and behavioral interventions from a community engagement perspective and teaches undergraduate and graduate courses in epidemiology and public health. She is director of the health policy and administration minor and a course director for the biomedical sciences graduate program. Before joining the faculty in 2022, she spent 15 years at the School of Medicine and Wake Forest Baptist Health researching and developing behavioral approaches to chronic disease management.

Sun in small doses

Though too much sun exposure can lead to skin cancer, getting just 15 to 20 minutes of sunlight every day is beneficial for our bodies. It triggers production of vitamin D, which is crucial for bone health and immune function and supports mental health and overall wellbeing.

Vitamin D also helps regulate circadian rhythms, gives us more energy and prevents fatigue and mood changes. Forty percent of Americans are deficient in vitamin D. When we don’t get that sunlight exposure, it can lead to chemical imbalances and less serotonin and melatonin production, two hormones that help regulate feelings of happiness and sleep cycles. Vitamin D also decreases the risk for osteoporosis and cardiovascular disease and even some cancers.

Boosts to physical health

Regularly being outdoors helps to reduce blood pressure even if you’re not being physically active. Just walking outside helps lower blood pressure and heart rate and reduces stress hormones like cortisol that can cause weight gain and mood disorders. It decreases our sedentary time because we tend to be more physically active when outdoors. Enhanced immune function also comes with being in the natural world. Breathing in natural chemicals released by plants and trees promotes natural killer cells in our bodies that fight infection and disease.

Spiritual benefits

Being outside exposes us to natural environments that are good for the soul. For mental health, there’s a clear connection between being in nature and reductions in stress and anxiety. There’s something calming and soothing about that connection with the natural world, which has positive effects on mood and brain activity. The late marine biologist Wallace Nichols coined the “Blue Mind” effect, the concept that blue spaces (water) can bring a sense of peace and calm to our lives.

Some studies show that nature also improves our working memory by about 20% compared to people dwelling in urban, modern industrial environments. There are benefits for productivity and creativity, too, which explains why so many artists go into nature to find inspiration. On a social level, being outside is good for community health, supporting social cohesion and helping families build stronger bonds.

A healing connection to earth

Being in nature also demands we redirect our attention away from our screens and creates new sensory connections and neural networks: You have to be conscious of how your body navigates in nature — a spatial and physical awareness of stepping over tree roots or climbing a hill. Your whole body becomes a part of your thought process and that connection with the earth.

When we are watching a sunset, we are experiencing the same natural world that generations before us once experienced. This reinforces the notion that we are a part of something bigger and everlasting, and hopefully encourages us to be better stewards of this world for generations that come after us. When we recognize ourselves as part of something larger, we gain a perspective that buffers against depression and existential dread.

Reconnection to the earth relates back to what native and indigenous populations have practiced for centuries. There’s a healing power in our connection with earth. When we engage with the natural world, we’re revisiting a powerful covenant between humanity and nature.

Interviews have been edited for length and clarity.