“Mama” or “Dada” did not come to mind when 1-year-old Leigh Ann Hallberg decided the time had come to speak. Her first words held more weight. They foretold a destiny.

“See pretty,” she said.

Hallberg doesn’t remember proclaiming those words, but over all these years she has carried her mother’s story about the unusual utterance. What she does remember from childhood: Hanging in her bedroom window were curtains festooned with circus animals, flags and the big top. One night, lightning flashed across a window, and the flash appeared to match the colors of the curtain —

“a strong memory,” Hallberg says. She was 3 years old and knew enough to pay attention.

She had seen an image bursting with color, arising from nature, that fascinated her.

“See pretty.”

She’s done that all her life. I spoke with her after visiting her exhibition, “Phenoms,” in Reynolda House Museum of American Art. Six large-scale abstract paintings mounted on wood structures jutting about four inches from the wall, as if thrust slightly into viewers’ space, hang in the West Bedroom Gallery. They are among a series of 20 paintings Hallberg completed after finding inspiration on walks with her tiny rescue dog, Lola.

Since 1999, until retirement this month, Teaching Professor of Art Hallberg (P ’12) taught in the art department in various roles, first as a visiting professor and, for a time, as an adjunct before teaching full time. Her courses included studio art fundamentals, sculpture, drawing, management in the visual arts and a first-year seminar on the avant-garde. Somehow, aside from the teaching, grading, coaching and advising, Hallberg found time to retreat to her studio — “heaven on earth” — to make art intended to spark conversations.

Born in Connecticut but raised in Ohio, Hallberg knew from a young age she wanted to be an artist. Cutting out felt fabric to mount on burlap banners, diving in with crayons into coloring books that featured dolls of the world, making crayon scratch art, Hallberg kept going even when a seventh-grade teacher told her she would never become an artist. “I thought that was kind of sad, but I didn’t pay any attention,” Hallberg says.

Hallberg had no artists in her family to emulate or museums to haunt on weekends. She found her Warren, Ohio, steel-town region “horrible,” lacking in artistic virtues and with characteristics she shudders to remember. High unemployment rates, “mafia, racism, you name it,” she says. “We actually had a mobster murder at the end of my block. A guy was out practicing golf in his front yard (and) got killed, got whacked.”

She was glad to leave. She went to what was then Mount Union College in Alliance, Ohio, and took “a zillion art courses” — painting in acrylics, watercolor and sculpture — and classes in literary interpretation. She moved to Buffalo, New York, for her fourth year, finishing her degree at what was then known as SUNY Buffalo. She liked the city. “I mean, I know that sounds funny. Most people don’t,” she says.

Six blocks away from home was the Albright-Knox Art Gallery, since renamed the Buffalo AKG Art Museum. Its rich history includes how in the early 1900s it helped introduce photography to the world as fine art and became a frontrunner in exhibiting abstract expressionist works. Hallberg was a frequent visitor. She didn’t have much money, but what little she had she saved for trips to The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City. On her list — and she got there — were “Treasures of Tutankhamun,” aka the King Tut exhibit, and “Degas in the Metropolitan.”

She continued to steep herself in art. She moved to Boulder, where she earned a Master of Fine Arts degree at the University of Colorado Boulder and later owned a frame shop in an art and drafting supplies store. She spent 1980 to 1990 in Colorado.

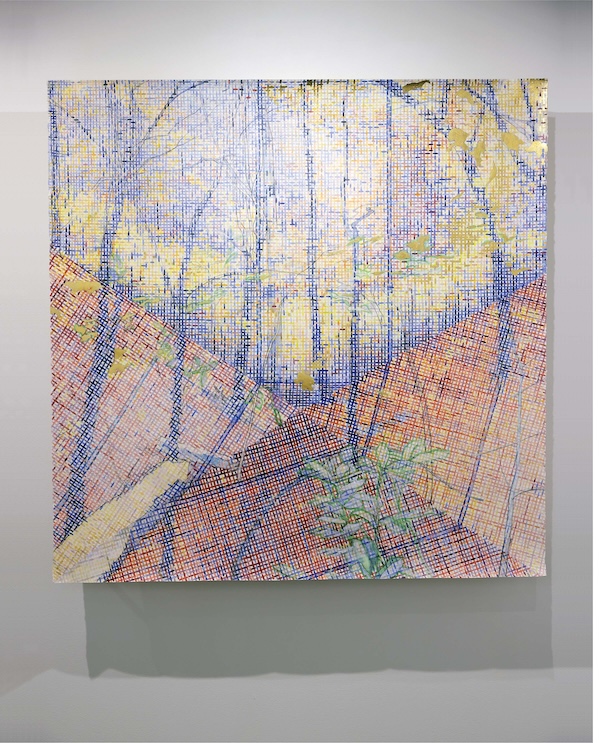

All her experiences studying art and, eventually, traveling to the best museums in the world played a part in Hallberg’s development. At Wake Forest, as an art teacher easily identified by her funky, colorful outfits and stylish round glasses, she sought to help students understand the fundamentals of critiquing art. How are the artists using texture? Line? Value? Shape? Color? How are these fundamentals organized? Are there big differences in light and dark? How do the artists “involve you and keep you involved” as the art is revealing itself?

“You’ve probably had this experience where you go — you love this painting — and look at the painting. You come back two years later, and you go, ‘I didn’t see that. I didn’t get it.’”

Hallberg adds, “It gives me goose bumps.”

As for creativity, she acknowledges adhering to an unpopular view. “I don’t think you can really teach it,” she says. “I mean, you can provide a space where it’s possible to be creative, but I don’t know that you can teach it.”

That comes from someone creative who says she was “wired that way … from the get-go” to become an artist, constantly looking at other art works and noticing how she might translate visual, emotional and physical feelings into her work. When she swims laps, which she does regularly, she’s “thinking about the water and how the water feels on my skin and what that might look like” in a painting or drawing.

“I don’t want to tell them. I want to suggest. And let it go from there.”

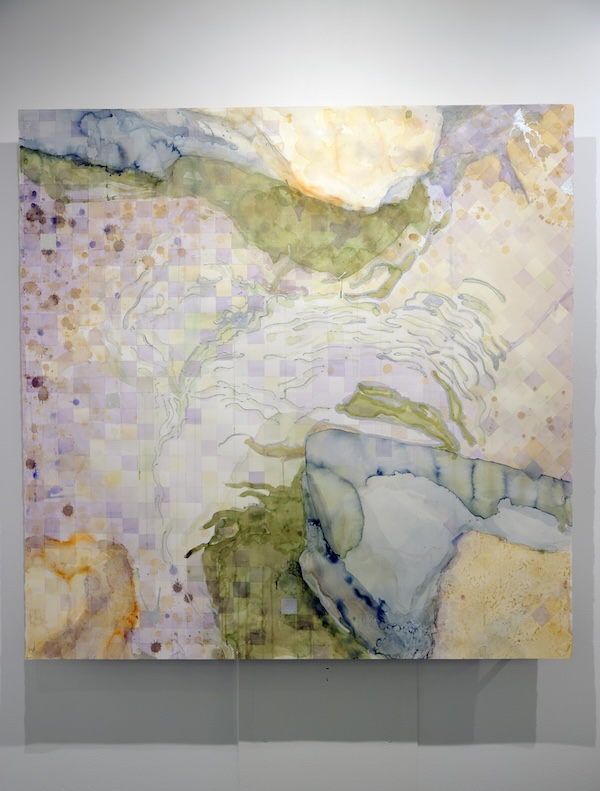

Eventually, her brand of kinesthetic contemplation proved revelatory on walks through the nearby woods and grounds of Reynolda House and the mountains. Hallberg can thank Lola, the white, fluffy rescue dog with a bit of an attitude, for the nudge. Hallberg and her husband, artist Paul Bright, until recently the University’s director of Wake Forest art galleries and programming, adopted Lola in 2014. They didn’t know at first how old she was — they later learned she was 5 — just that she was a good companion who wanted to be with them every minute. One day, around 2015, Hallberg realized in Scales Fine Arts Center that Lola decided school was “boring and that there was actually a park out there, and ‘Why, in the world, would she want to be in class?’” Lola’s humans got the message. Hallberg’s daily, one-hour walks with Lola evolved; they began to feel like museum visits and helped Hallberg regain a sense of stability during a stressful time. Lola was happier, and so was Hallberg.

“You just start noticing things,” Hallberg says. “I was remembering even from childhood how amazing the world is.”

She began taking photos, sketching and imagining the viewpoints of birds and insects. She reveled in contemplating the complexity of nature and “the hubris” of thinking that a human might understand it all. She was inspired. After her father’s death in 2017, she began what she calls the big paintings — the ones that went on exhibit last September in Reynolda House and the others in the series that have been rotated into the gallery before the exhibition ends on Oct. 19.

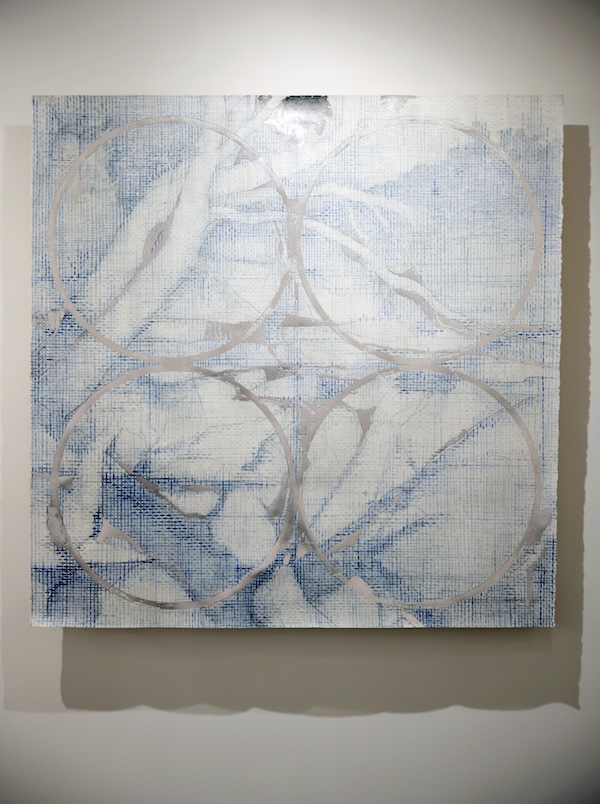

The description of the exhibition says the large-scale, square abstract paintings are “neither portrait nor landscape.” They are “a pretend space in which the viewer is able to reconsider and reimagine” their experience with the works. Nearly all of the paintings are composed with what Bright calls “a spectrum of color — cool playing off warm, descriptive versus allusive — just as the compositions themselves occupy different places between poles of depiction and abstraction.”

“It’s about the light,” Hallberg told me. “The coolest thing about those paintings is that they change.” The exhibition space or time of day or how one walks around the paintings can make a difference.

In a public talk at Reynolda House last fall, Hallberg made it clear that she wanted to use only enough representation in the paintings to ground the viewers and give them a clue about where they were. She shortened the exhibition’s original title to “Phenoms” after she decided “Phenomenological Walks” was too much of a mouthful.

Examining one painting, the viewer can see a log and “waves” that might indicate water. “I don’t want to tell them. I want to suggest, and let it go from there,” Hallberg says. She sees paintings as “arenas” that allow the viewer to participate. (Having the canvases jut from the wall on their wooden bracing that Hallberg calls “sleds” helps further the goal.) For both Hallberg and Bright, their way of creating art can be traced back to an influential mentor: the late James Rosen. A gallery’s biography of Rosen notes how the artist would paint over his works on canvas with monotonal hues he called “veils” so that the works can be “completed by the observer.”

“It’s about the light. The coolest thing about those paintings is that they change.”

Bright says of Rosen, “He instilled in us that paintings are places where experiences happen. … You don’t want to over-depict.”

In one “Phenoms” painting, Hallberg invites the viewer to experience her version of entanglement theory, which suggests that when two particles have become entangled, no matter how far apart they are later, they remain connected on a quantum level and react.

Bright, who moderated the talk, noted how “the entangled quality … gives it a sort of a cosmic quality.” So does the salt that Hallberg worked into the painting to evoke “tiny explosions.”

Veronica Kavass, a former curator who teaches creative writing at the University of North Carolina School of the Arts, captured the beauty of Hallberg’s series in a June 2024 essay about “Phenoms.” (Kavass became grants and stewardship manager at Reynolda House in late fall.) An excerpt:

There’s a kind of art where the artist seems to hover over you — they’ve crafted each detail intentionally, shaping your experience in a way that makes it clear how they want you to engage with their work. Sometimes this can be a good thing, but most of the time it feels too controlling. Hallberg’s work does the opposite: they invite and provide entry, even potential guideposts. For example, the interplay between depicted elements and abstraction, metallic sheens and watercolor washes that introduce a dynamic contrast, capturing light in a way that suggests both the ephemeral and enduring aspects of nature. Yes, the mix of media and tones creates a visual space where the natural world is both familiar and mysterious. But it doesn’t feel like there is a prescribed way to understand the “Phenoms.” They function more like semi-permeable membranes — inviting some ideas and feelings in while filtering others out. …

An audience member at the Reynolda House talk commented in the Q&A portion of the event that the paintings “brought me a new way of looking” — an invitation to experience the natural world and not always frame something in one’s mind as a photograph. This kind of seeing is unpredictable “and not standard,” she said.

Hallberg has a phrase for the predictable in artworks: “It’s nailed down, and then you’re gone.”

Not so with “Phenoms.” Arising from contemplation, this example of creative expression invites one to linger, to experience wonder and, above all, to feel how good it is to be outside. Lola understood.

Only a few weeks after the Reynolda talk, I was distraught to learn that Lola had died. But at least I could say I had met her on a warm autumn day when she received “good, old girl” pats from Bright and Hallberg. I understood then — and appreciate even more now — the role she played with that nudge to send Hallberg into the woods on sensory journeys filled with flights of reverie and flashes of insight.