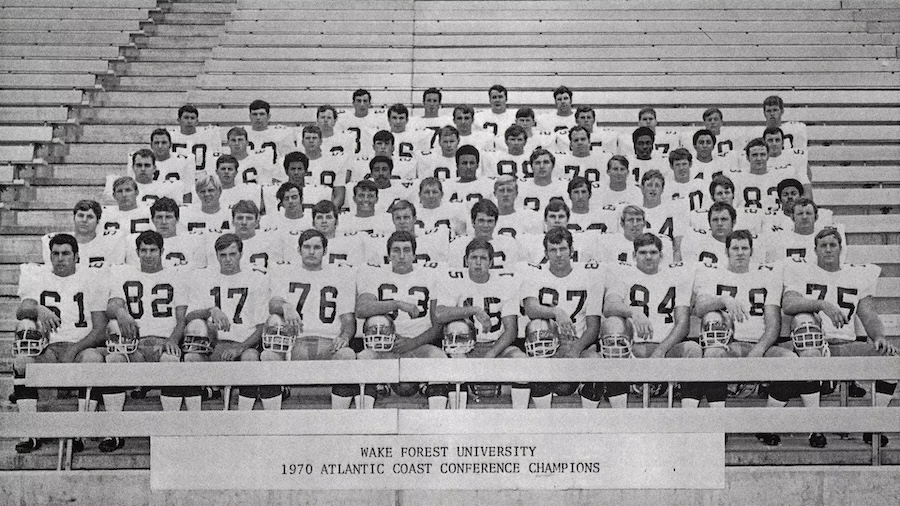

Little was expected from the Wake Forest football team in 1970. After 10 straight losing seasons, there was no reason to believe the 1970 team would break that streak. Sportswriters predicted the team had “no offense, no defense, no hope.”

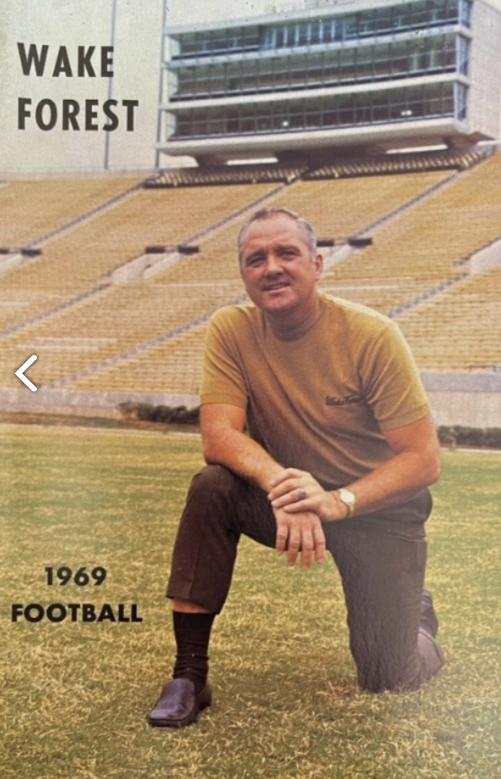

Coach Cal Stoll, who started as head coach at Wake Forest in 1969, used that as motivation to instill a deep belief in his players that they could win with hard work, sacrifice and heart. The season started slowly with three straight losses before the team rallied to finish 5-1 in the ACC and 6-5 overall and claim Wake Forest’s first ACC football championship.

David Doda (’71), a tight end on the team, remembers that special season — and the tumultuous time period — in his new book “No Offense, No Defense, No Hope! How an Old-School Coach Transformed a College Football Team of Perennial Underdogs and Won a Championship for the Ages.”

“The bonds we forged through shared struggle, sacrifice and, ultimately, triumph, transcend conventional friendship,” Doda writes. “What we experienced as a team created a brotherhood that has withstood the test of time.”

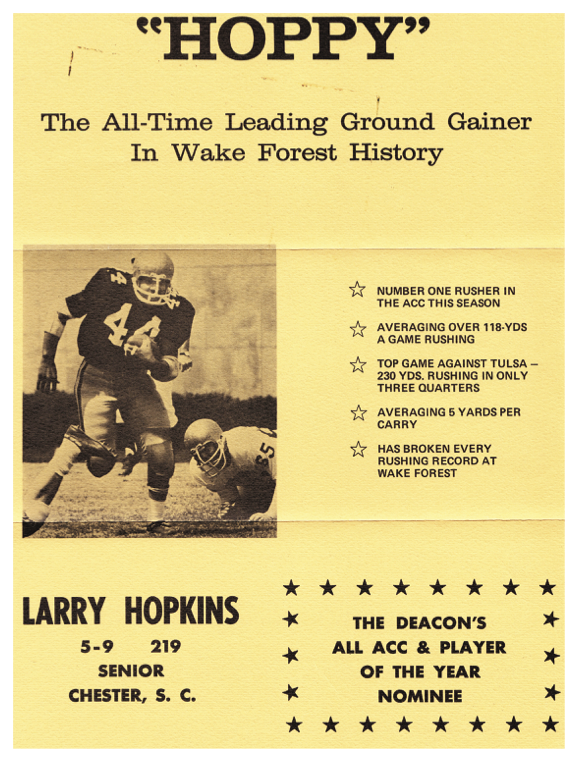

Five players on the team were later inducted into the Wake Forest Hall of Fame: quarterback Larry Russell (’71, P ’01, ’03), running back Larry Hopkins (’72, MD ’77, P ’12), defensive tackle Win Headley (’71, MA ’75, P ’05) and linebackers Ed Bradley (’72) and Ed Stetz (’72).

Aside from football, alumni will enjoy remembering the Thunderbird Drive-In, Simos restaurant and trailblazing Winston-Salem sportswriter Mary Garber. And there are some stories that will surely surprise some readers: For instance, Joe Namath and the 1969 Super Bowl champion New York Jets played an exhibition game in the brand new Groves Stadium in 1969.

“I think it’s a trip down memory lane for those that lived through it, and if you didn’t live through it, it’s like, ‘Is this what it was like back then?’” Doda says.

After graduating with a degree in physics, Doda stayed at Wake Forest to take master’s-level physics and math courses. He also took education courses and did his student teaching at R.J. Reynolds High School in Winston-Salem before earning a Ph.D. in physics from the University of Florida. He worked for a defense contractor in Virginia for two decades before founding an IT company and a software venture. He and his wife, Nancy McIntyre Doda (’74), have two children and two grandchildren and live in Brookfield, Vermont.

The championship team will be recognized at the Wake Forest-SMU Homecoming football game on Oct. 25. Doda will sign copies of his book from 2:30 p.m. to 4:30 p.m. on Oct. 24 at the University Bookstore on Hearn Plaza.

Kerry M. King (’85), retired senior editor of Wake Forest Magazine, caught up with Doda recently to reminisce. Here are excerpts from their conversation, edited for length and clarity:

Before we jump into your book, I’d like to learn more about your time at Wake Forest outside of football. Were there any professors who influenced you?

The one who impacted me the most was Greg Pritchard in philosophy. He would chomp down on his pipe, but he wouldn’t light it in class. One of the things that I remember from Philosophy 101 is (him saying), “Whatever you do for your life’s work, make sure it’s recreation to you, then you’ll always love going to work.” He was a wonderful man and a very good friend.

You were a student during a time of social and political upheaval in the country. Wake Forest wasn’t a hotbed of student activism, although there were some protests and the 1970 march on the President’s house to protest the Vietnam War. You wrote that Coach Stoll made it clear that football players should stay out of it. I’m curious about this disconnect and what it was like to be a student then.

He just said, “You’re here to play football, and we don’t do that kind of stuff.” Cal had no use for outside activities. He was focused on football, and that was it. You have to remember that change was normal — besides the social unrest and racism and violence, which was shocking — during that time. Wake had just allowed dancing on campus. A year and a half after I graduated, there was a co-ed dorm (now Luter). That’s the kind of steep curve you had during that time. Never again in such a short timeframe will we see such rapid change from Eisenhower and apple pie to the Beatles and (Rolling) Stones and drugs and everything in between. I remember coming back to campus one year on I-40 and there were tanks blocking every exit (because of riots in Winston-Salem).

I vividly remember the draft. We went to a basketball game, and I drove back to campus with a couple of guys, and we parked outside Taylor (Residence Hall) and sat in the car listening (to the radio). They’d read off a hundred (birthdays), take a break, and then read another hundred. We missed the first hundred dates. (So, he didn’t know if his number had already been called.) We caught the second hundred, and I wasn’t in that. Then they called the third group, and I wasn’t in that. The last part came on, and (my birthday) was number 335. (So he was unlikely to be drafted.) I said, “Thank you,” and went on with my education. It was just a different world.

Why did you decide to write this book, 55 years after the championship?

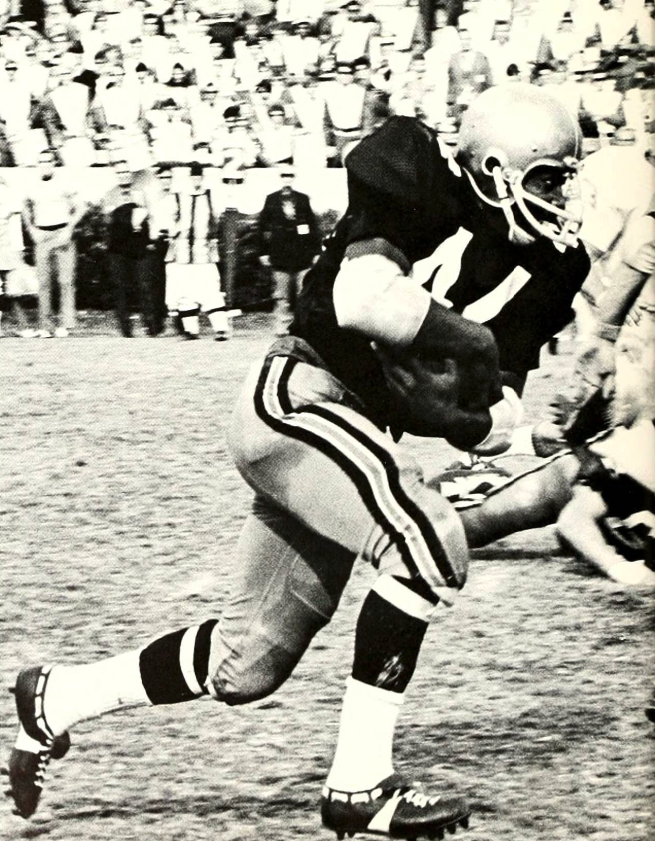

It had been on my bucket list, and it was time. I wanted to tell our story, the feelings behind it and the coach that pulled us together. I feel it is a timeless story for all ages. I’m going to get a little emotional here. On Aug. 12, I had triple bypass surgery, and I wanted to make sure it was finished. I made it by two days. The cover image of a guy carrying the ball is a likeness of (running back) Larry Hopkins. (He became a beloved doctor with a residence hall recently named in honor of him and his distinguished wife, Beth Norbrey Hopkins (’72, P ’12).) You can see a “4” on his jersey, and he was number 44.

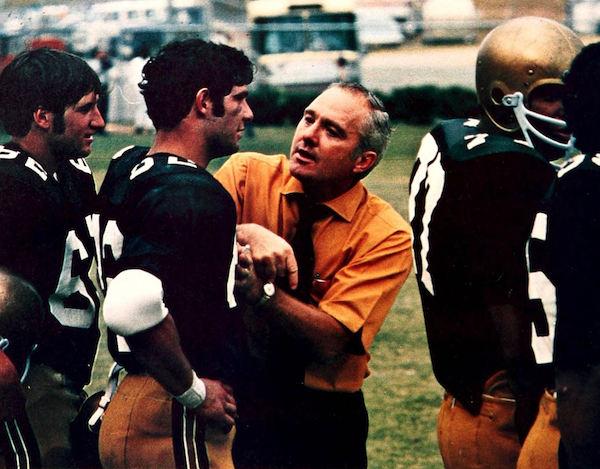

Coach Stoll came to Wake Forest in 1969 from Michigan State, where he was a longtime assistant. You wrote that he was a tough “old school” coach who put players through brutal practices to toughen you up or weed you out. How else would you describe him?

He only wanted people that wanted to play. In my class, there were 30 of us. When I graduated, there were 12 still left on the team, and 11 of us were starters. The rest had dropped out. He was very knowledgeable in terms of understanding his players and getting the most out of them. He was very good at evaluating the talent that he had and molding his offense and defense to the talent, as opposed to saying, “This is our defense, we’re going to use it no matter what (the talent).” The two Larrys (Hopkins and Russell) made our offense work. The defensive unit was amazing with Headley, Bradley, Stetz, Terry Kuharchek (’72) and others. Stoll saw the talent he had and fit the pieces together into a winner.

“To every single one of us who made it through those two years, it brought a deep sense of personal accomplishment — an indescribable feeling of pride we would cherish forever.”

As you write in the book, Coach Stoll set the standards and expectations from his first practice in 1969. But that team finished 3-7 and you started out 0-3 in 1970 with lopsided losses to Nebraska and South Carolina and a close loss to Florida State. What inspired you to believe that this could be a different era for Wake Forest football?

The opening game at NC State in 1969 (which Wake Forest won 22-21). Cal turned out the lights (in the locker room before the game), and we heard, “Glory, glory, hallelujah” (“The Battle Hymn of the Republic”), and we burst out of the locker room in a frenzy. That made us believe in ourselves, and it never stopped. Even after our third loss (in 1970), a sportswriter said we were the best no-win team in the country. It was just the belief that Cal had instilled in us. We believed in ourselves. There was never even a thought that we couldn’t win.

Then came your first win at Virginia, followed by unbelievable tragedy. On the way back to Winston-Salem, the team buses came upon a car accident in which the girlfriend of quarterback Larry Russell had been killed. Can you talk about that?

We were coming back from Charlottesville. Rain-soaked roads. Traffic slowed, and we heard there was an accident ahead of us. Larry found out the car had Massachusetts tags (where his girlfriend lived). He was screaming to get out there. There was no more celebration. It was just tears and praying. Larry went home for a week and came back, and we had the memorial service (in Wait Chapel). I can tell you that was the last place I wanted to be, but I had to be there for Larry.

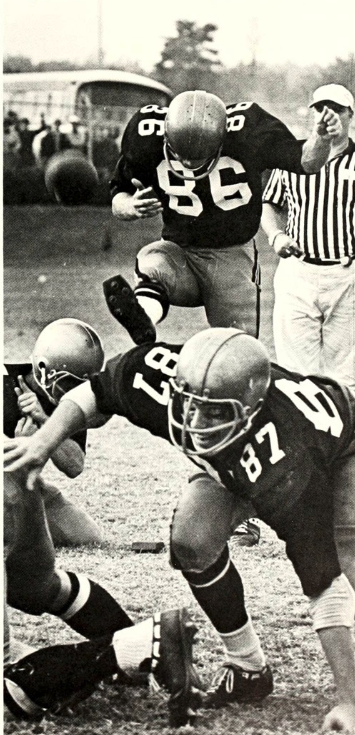

After a couple more wins, the team faced North Carolina in Groves Stadium. Down by six points with three minutes remaining, Wake Forest put together a 92-yard drive to score with 12 seconds left and won 14-13. You call it “arguably one of the greatest clutch performances in ACC history.” You were on the field for that final drive. What do you remember most about that game and that drive?

It’s still known as “The Drive.” There was never a doubt in anybody’s mind that we were going to score. Even when we were down on the (Wake Forest) six-yard line (after losing two yards on the first play of the drive), when Steve Bowden (’72) made that fabulous catch to give us a first down (on 3 and 12), we were just going to do this. It was a very special thing. We were playing as one, and we were going to win.

Carolina had an All-ACC linebacker named John Bunting (a future North Carolina head coach) and an All-America running back, Don McCauley. Both had great college and NFL careers. John and I lined up opposite each other on every play. I won the day, which is not a good thing for an All-American against a know-nothing tight end. Bottom line, we played out our hearts in the game against a very good Carolina team and won. (Future Wake Forest coach Bill Dooley was the Tar Heels’ coach.)

How did your experience on the football team influence you?

When you really want something, never give up, keep on trying. Give it your best shot, believe in yourself, put your heart and soul into it. Just go for it, do whatever it takes, even if it’s against all odds, because you’ll never get another chance. That’s what I learned from Cal Stoll.

I think the whole experience cemented the confidence that I could survive adversity. I was a linebacker in Cal’s first season. The linebacker coach hated my guts because he thought I was a hippie (because) I wore a tie dye scarf (that Doda still has). I went to Cal and asked to be switched to offense and tight end. What football taught me is when you want something, find a way to get it.

What is it like to get back together with your teammates?

We have a “den mother,” Donnie Brown (’73, MAEd ’76), who keeps us informed and gets the team together for lunch quarterly (for those in the Winston-Salem area). There was a memorial service for Larry Hopkins (who died in 2020) that we all came to. So, we’ve seen a lot of each other over the years. Every time we’re together it’s just like an old friend; we were never apart. The sadness of it is that everybody is not here. Hoppy (Larry Hopkins). Win Headley. My freshman roommate, Terry Kuharchek, just passed away last year. That’s going to happen more and more, but at least this book celebrates who we were for posterity.

For more information on the 1970 team and to order the book: www.wf70.com