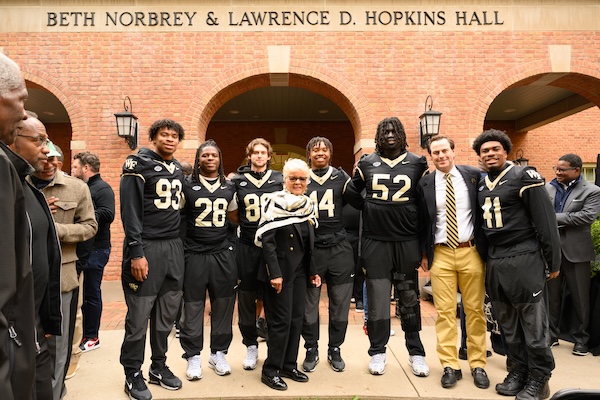

Beth Norbrey & Lawrence D. Hopkins Hall isn’t just a building, their son David Hopkins (’12, MA ’15) said at the dedication of the residence hall on Oct. 25. “It’s about legacy. It’s about what it looks like to open doors for others, even when you had to break them down yourself.”

Beth Norbrey Hopkins (’73, P ’12) has had a decades-long career in law, education and community outreach, and was one of the first two Black female residential students at the University.

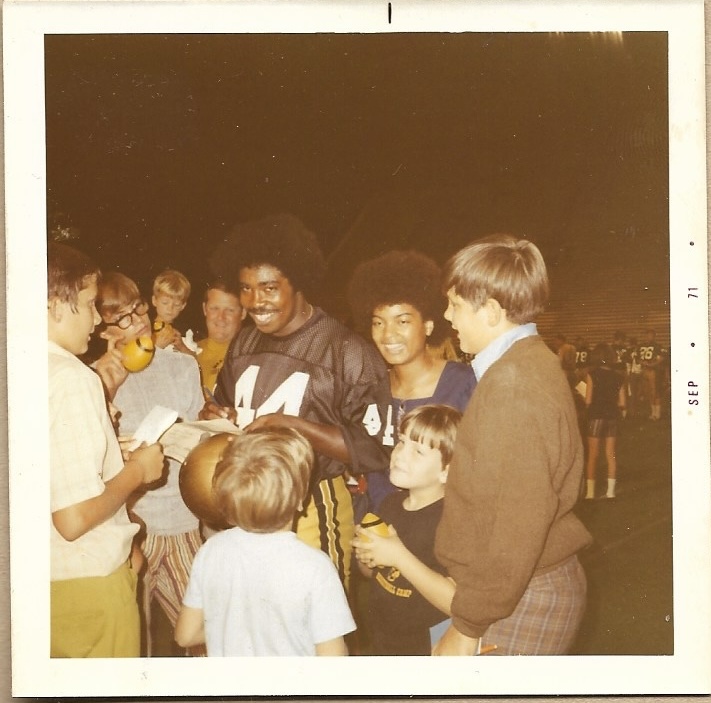

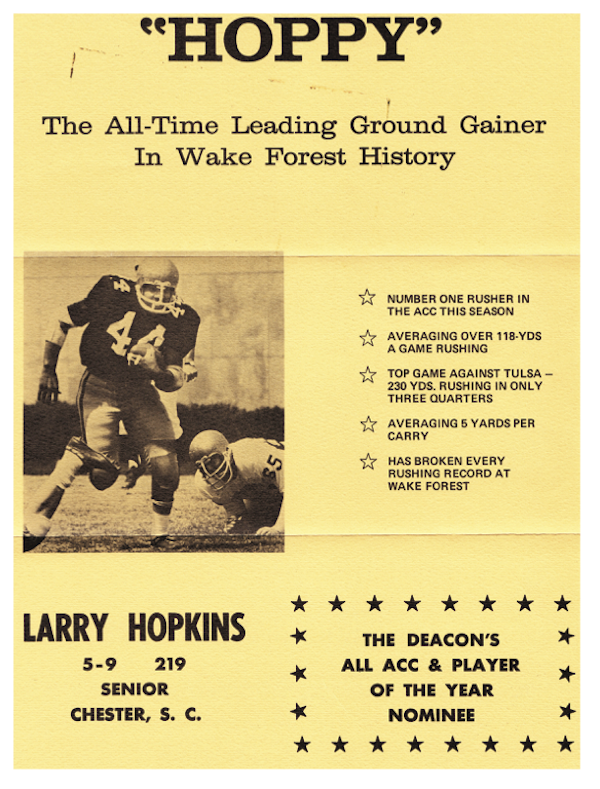

Her late husband, Dr. Larry Hopkins (’72, MD ’77, P ’12), a football star at Wake Forest, became a well-known physician who improved access and outcomes for women’s and neonatal health.

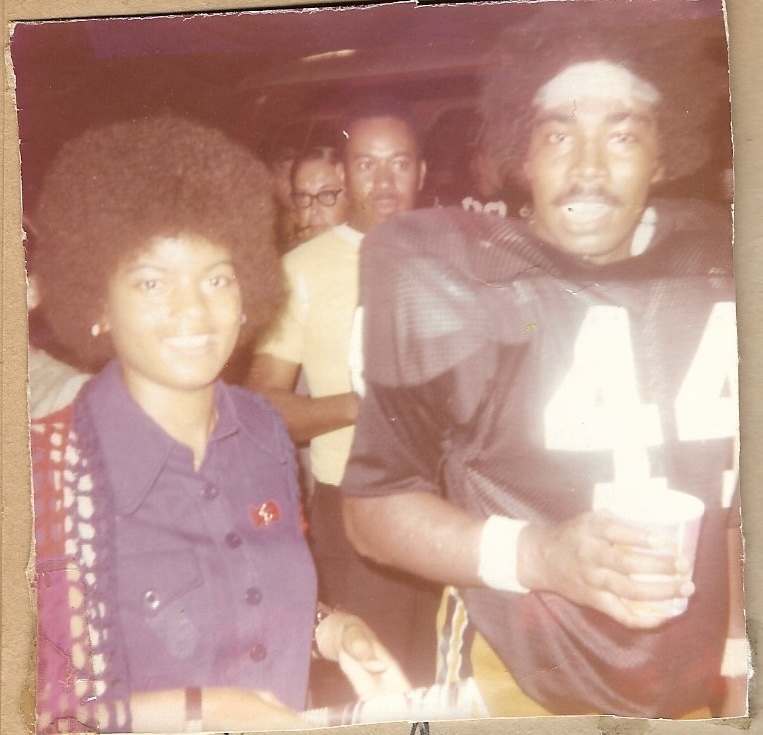

The couple met in front of Wait Chapel in 1970 and were married for 47 years. They have two children, Michelle and David, and two granddaughters.

“Together, they modeled a life of service and strength. A life built on the belief that Pro Humanitate isn’t just a motto — it’s a way of being,” said David Hopkins. “They didn’t just love Wake Forest. They challenged it to be better. …

They mentored. They nurtured. They listened. Because for them, helping others wasn’t optional — it was their purpose.”

In her opening remarks, President Susan R. Wente emphasized the importance of honoring Wake Forest’s history through the stories of those who have left the institution and community better than they found it.

“The crowd gathered here today represents just a fraction of the lives changed by two people named Beth Norbrey and Lawrence D. Hopkins,” Wente said. “Two people who each — in their own right — embody lives of learning, discovery, character and leadership. Two people who have asked hard questions and courageously pursued the answers, who have given wise counsel, never stopped learning and have ceaselessly given of their time and talents to do good in the world.”

A double Deac, Larry Hopkins was the first Black student to graduate from Wake Forest with a degree in chemistry. He then went on to earn his medical degree from the School of Medicine, becoming a prominent OB/GYN who delivered thousands of babies — including NBA star Chris Paul. The University awarded him its highest recognition, the Medallion of Merit, in 2020.

“The early ’70s at Wake Forest were a time of exploration and revolution. Afros were a foot high, and skirts were a half yard long,” Beth Hopkins shared at the dedication. “Initially, we were not welcome in any Wake Forest society, fraternity, cheerleading squad, on-campus parties and, in some cases, we were not welcome in the classrooms. Yet, we were not afraid, because we faced unpleasant situations together.

“We were warriors fighting for our place at Wake Forest, and we created a pathway for future students of all stripes. Proudly, Wake Forest has embraced the pathway of change and moved to create opportunities where all students here are treated with fairness, and there is the expectation of students working hard and serving humanity.”

After the program, sophomore Ty Monroe spoke with Hopkins, who encouraged him to engage with the alumni, faculty and community leaders because their perseverance through racism and discrimination helped create the opportunities students have today.

“That perspective left me feeling both grateful and responsible: grateful for the doors their generation opened and responsible to use the resources and relationships we have now to support those who come after us,” Monroe said. “As an RA, that reminder to connect, learn and pay it forward really stuck with me.”

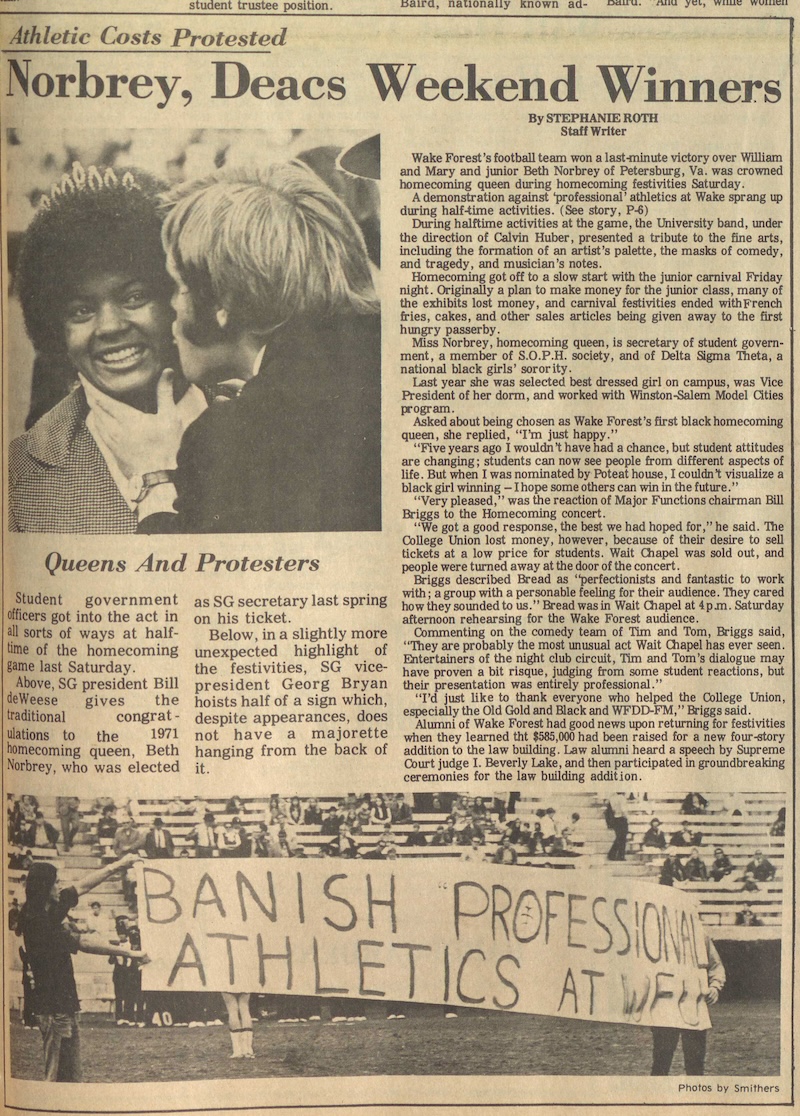

Hopkins was named Homecoming Queen in 1971. This year’s Homecoming Queen, senior Chase Clark, said that “to follow in her footsteps is both humbling and deeply inspiring.”

“As this year’s Homecoming Queen and President of the Black Student Alliance, I feel profoundly connected to Professor Beth Hopkins’ legacy,” Clark said. “Her courage and determination paved the way for students like me to take up space with pride and purpose. She transformed what representation could mean at Wake Forest — showing that leadership, intellect and grace can coexist in powerful ways. I’m grateful to help continue the work she began in creating a more inclusive and empowering campus for all.”

This story originally appeared at news.wfu.edu.

Creating Pathways for Future Students

Beth Norbrey Hopkins (’73, P ’12) reflected on her experience at Wake Forest at October’s dedication of Beth Norbrey & Lawrence D. Hopkins Hall.

Good Morning Trustees, Dr. Wente, administrators, my family and friends gathered here today. The tears have not stopped flowing as I am truly humbled by the dedication of this building in honor of my late husband, Dr. Larry Hopkins, and me. Thank you, Wake Forest, for this historic opportunity, which acknowledges not only the Hopkins journey but the journey of the students of color who preceded us and laid the foundation for creating great memories — and for my friends with whom I have enjoyed a 50-year friendship because of this institution. Also, I stand before you today because of His grace and mercy, and although the journey was not easy, I am thankful for the time spent here.

Larry Hopkins and I met in the spring of 1970 in front of Wait Chapel. We were married for 47 years, had two children, have two granddaughters, and Wake Forest was the bond that sealed our relationship. He loved the members of the 1970 championship (football) team and later was a compassionate doctor who loved delivering babies, teaching residents and providing medical care for all his patients irrespective of their economic status. The physicians in East Winston guided him during early days of practice here. Moreover, he was grateful to Baptist Hospital, the OB/GYN department in particular, and to Novant for allowing him to guide expansion of medical services to the community. Our friends, and the WSSU and the Winston-Salem communities, welcomed him and supported his practice with great enthusiasm.

When I graduated from Wake Forest with honors, the law school did not accept me, noting that there already were “two of them.” I was not mature enough to understand that a plan had been mapped out for me. I just had to wait my turn.

Often, I wondered why a guidance counselor from Panama City, Florida, sent Larry to a junior college in the mountains of North Carolina when there were so many options for him academically. Interestingly enough, he was not recruited by any team for football because his family had moved all over the country courtesy of his father’s commitment to the Air Force. But divine providence was at work. Larry always loved Lees-McCrae College in Banner Elk, North Carolina, where he was a running back and returned punts. In the spring of 1970, a Wake Forest football coach lured him away, we met and the rest is history. Had he not attended LMC, we would have never met.

When I entered Wake Forest, fresh from years of tumultuous civil rights struggles in Virginia, courage was my constant guide. There were about 18 Black students on campus in the yellow and red fall of 1969. My roommate Deb Graves (McFarlane) (’73) and I were the only two Black women who lived on campus initially, and the other two Black women, Linda Holiday (’73) and Awilda Gilliam (Neal) (’73), joined us the second semester. The number 18 included 11 Black athletes. We were all affirmative action students. You may have misgivings about that term. But you should not. At Wake Forest, affirmative action did not mean that standards were adjusted to accommodate us. It meant that this school dared to bring in academically talented Black students who would help broaden perspectives of students of European descent who were uninformed as to our accomplishments and stamina.

There was one Black professor, who taught in the religion department, and no Black administrators. Since we were from the say-something generation, we encouraged changes in the look of the decision makers and helped to increase diversity in the faculty and student body.

Proudly, Wake Forest has embraced the pathway of change and moved to create opportunities where all students here are treated with fairness, and there is the expectation of students working hard and serving humanity.

There were three Blacks on the basketball team and eight on the football team. To provide a frame of reference for the entire ACC, Clemson had one Black on the basketball team, and he sat on the bench. And in 1970, when we upset Clemson at Groves Stadium, there were no Blacks on the football team. Imagine that!

While students today have the Snoop Doggs, Lil Waynes and 50 Cent, our world consisted of poets Paul Laurence Dunbar, Claude McKay, Countee Cullen, the infamous Langston Hughes who too sang America, and the four-lettered sports athlete, Phi Beta Kappa graduate and Broadway performer Paul Robeson. We were valedictorians, salutatorians and top 10% entering freshman.

The early ’70s at Wake Forest were a time of exploration and revolution. Afros were a foot high, and skirts were a half yard long. Initially, we were not welcome in any Wake Forest society, fraternity, cheerleading squad, on-campus parties and, in some cases, we were not welcome in the classrooms. Yet, we were not afraid, because we faced unpleasant situations together.

We were warriors fighting for our place at Wake Forest, and we created a pathway for future students of all stripes. Proudly, Wake Forest has embraced the pathway of change and moved to create opportunities where all students here are treated with fairness, and there is the expectation of students working hard and serving humanity.

Wake Forest pushes the narrative of spiritualist John Wesley, who once said, “Do all the good you can by all the means you can, in all the places you can, at all the times you can, to all the people you can, all as ever you can.”

When I graduated from Wake Forest, I did not anticipate coming back ever, and now you all cannot get rid of me. All four of the presidents with whom I had the pleasure of engaging contributed to my experience at Wake Forest. Dr. Ralph Scales was out front on the issues of equity and justice. One of my scholarship funds did not arrive on time for me to register. The Wake Forest treasurer at the time was sending me back to Virginia, and Dr. Scales, a member of the Cherokee tribe and an old-fashioned progressive, understood how it felt to be marginalized. He reached into a funding source, gave me a scholarship on site, and allowed me to register in a timely manner.

Dr. Thomas Hearn, a steady and compassionate leader, had a broad-based interest in fairness and creating opportunities for inclusion. He placed a high value on other people’s culture and experiences and believed everyone who came to Wake Forest could be successful. He created a position for me in the Legal Counsel’s office where I had the great experience to develop as an education attorney.

Dr. Nathan Hatch spearheaded the 50-year celebration of the 1962 enrollment of Ghana native Ed Reynolds (’64), who became the first Black full-time undergraduate to enroll at Wake Forest, and the outstanding 50th anniversary celebration in 2020 of my three colleagues and me integrating the Wake Forest residence halls. Universal student enrollment increased under his leadership as he strengthened institutional support for all students.

Challenges to academic freedom have created unprecedented storms through which Dr. Wente has guided us skillfully and with great dignity. She has maintained the university’s reputation for doing what is equitable and doing what is right. She built upon the foundations of Wake Forest courageously as we confront a brave new world. She has led with integrity and insists that Wake Forest honor the principles of respect for persons who are derived from a plethora of cultures and economic experiences.

In closing, I owe a special thanks to the history department and law school faculties for providing valuable support during my time spent in each entity. I have a loyal group of friends who supported Larry and me through scores of projects and gave me strength and purpose following Larry’s transition. Thanks to my USTA family for giving me the green light to make a difference, and thanks to my children, sister and Hill, Bowes and Norbrey relatives, and my Hopkins family who kept the sunshine in my life after Larry passed.

And so together our community will traverse through the current storms. Many of us have been working and praying for humanity a long time.

I ask that you sing for justice, that you run for fair play and that you shout for the greater good; as a Wake Forest and Winston-Salem community, we are not afraid. And as one of the spirituals of my ancestors asserts, there are days when I could not see my way, but I am not tired, yet. Wake Forest, you have

created a glorious memory for my family, for me and for future generations.

I will love this place forever.