What is the sound of an economic mashup?

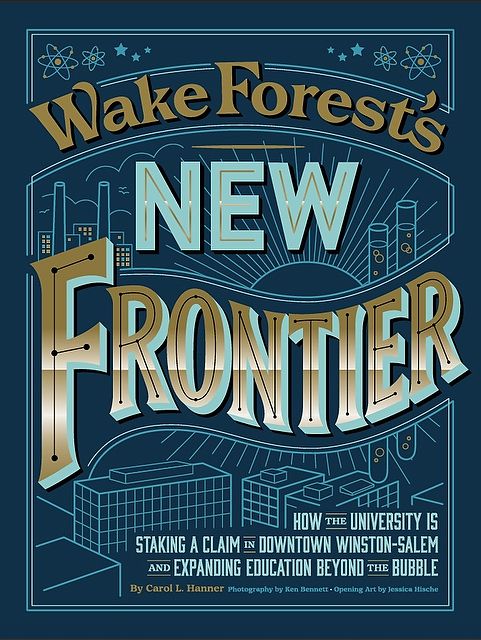

You can hear it — and see it — these days in downtown Winston- Salem, where the University is making what could be its biggest move in 60 years.

Take old cigarette factories and tobacco warehouses, repurpose and renovate them, add large companies, startups, creative space, “eds and meds,” and a commitment to the cultural hub and community, and you have Wake Forest Innovation Quarter. Founded in the mid-1990s as Piedmont Triad Research Park and now expanding at breakneck speed, the biotechnology research, education and business district owned by Wake Forest Baptist Medical Center represents Winston-Salem’s convergence economy, its big bet as cities strive to become the 21st-century best versions of themselves.

Jennifer Vey, a Fellow with the Centennial Scholar Initiative at the Brookings Institution and co-director of its Anne T. and Robert M. Bass Initiative on Innovation and Placemaking, says of innovation districts: “It’s really about proximity and density that creates the kind of collaboration and information exchange that you need for some of these sectors to thrive. … The power of innovation districts is you’re seeing co-location of different kinds of activities. Universities, medical centers, large companies with incubators and startups, you’re seeing them come together, overlaid with the ‘place’ piece of it — public spaces, coffee shops and other places that bring people together in informal ways, a chance to intermingle.”

Jennifer Vey, a Fellow with the Centennial Scholar Initiative at the Brookings Institution and co-director of its Anne T. and Robert M. Bass Initiative on Innovation and Placemaking, says of innovation districts: “It’s really about proximity and density that creates the kind of collaboration and information exchange that you need for some of these sectors to thrive. … The power of innovation districts is you’re seeing co-location of different kinds of activities. Universities, medical centers, large companies with incubators and startups, you’re seeing them come together, overlaid with the ‘place’ piece of it — public spaces, coffee shops and other places that bring people together in informal ways, a chance to intermingle.”

The University is following this synergistic path to the old tobacco buildings. Years ago, the School of Medicine moved some researchers and programs into Innovation Quarter. In 2014, the medical school was looking to move its medical education programs there but would not need all the available space in two former R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Co. buildings being renovated by Baltimore-based developer Wexford Science & Technology, LLC.

The University is following this synergistic path to the old tobacco buildings. Years ago, the School of Medicine moved some researchers and programs into Innovation Quarter. In 2014, the medical school was looking to move its medical education programs there but would not need all the available space in two former R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Co. buildings being renovated by Baltimore-based developer Wexford Science & Technology, LLC.

Wexford let President Nathan O. Hatch know the University might want to expand the medical school deal because of the additional space. Hatch began talking with officials at the medical center. What if there could be a new form of collaboration around biomedical science and technology, which Hatch has called “the most cutting edge and dynamic field of study in contemporary society?”

eanwhile, another thought bubble was percolating around coffee.

Financial Aid Director Bill Wells (’74) had read a local newspaper article saying tax credits for renovating the tobacco buildings would expire soon. Wells, a history major with a fascination for historic preservation, discussed the news with Provost Rogan Kersh (’86) over coffee during a monthly meeting. Wells knew of the medical school’s plans and wondered: What if we could take some students from the Reynolda Campus downtown?

Kersh was intrigued. He talked to President Hatch, joining multiple conversations the president had underway. As the conversations coalesced, the momentum was unmistakable — the perfect illustration of how “what if ” conversations can lead to “wow” collaborations.

This was a wave worth riding for education innovation. The result will be historic.

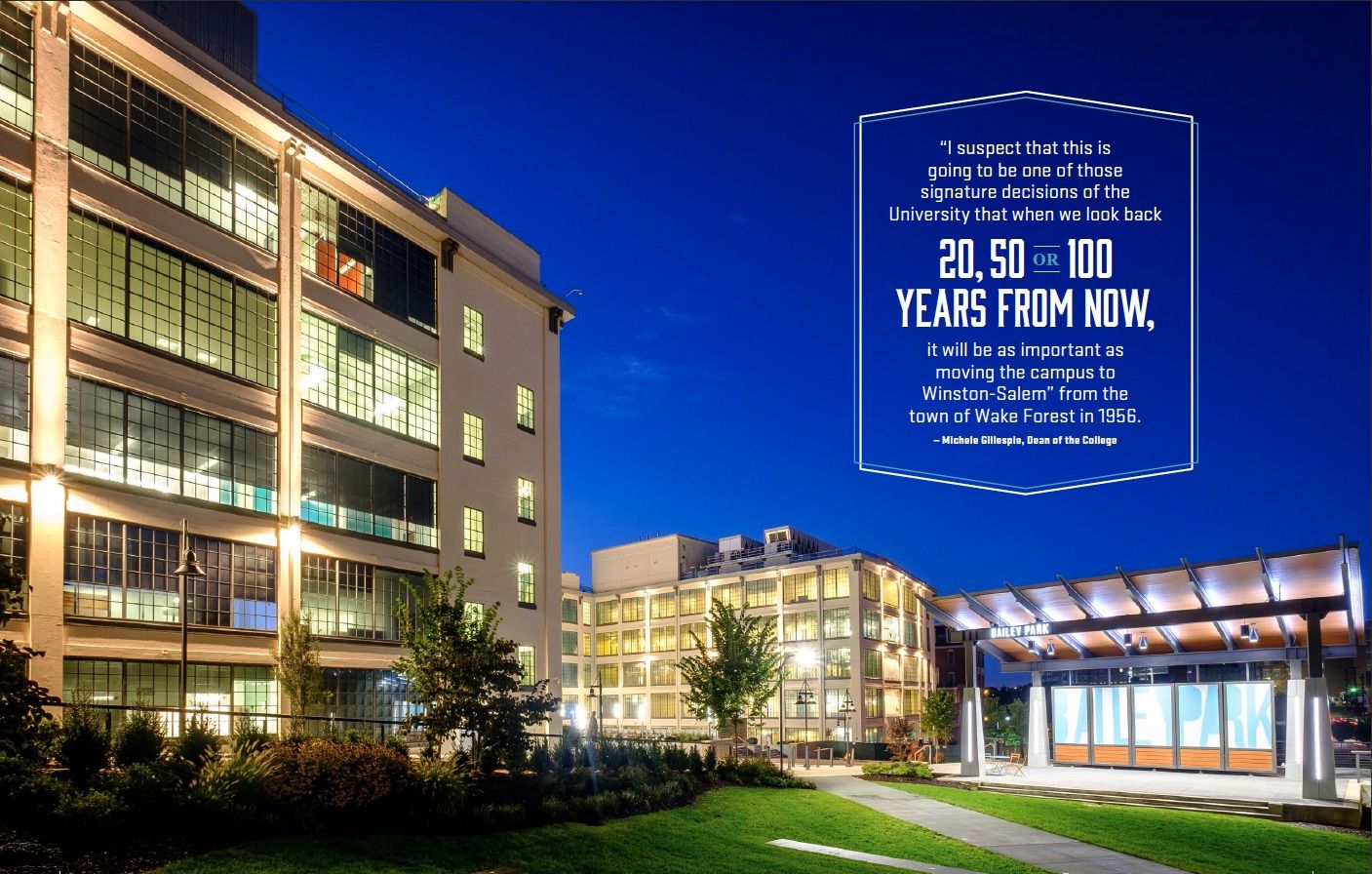

Dean of the College Michele Gillespie, a history scholar, puts it this way: “I suspect that this is going to be one of those signature decisions of the University that when we look back 20, 50 or 100 years from now, it will be as important as moving the campus to Winston-Salem” from the town of Wake Forest in 1956.

Photograph from the 1940s showing the tobacco district and the R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Co. headquarters, an art deco-style skyscraper that until 1966 was the tallest building in North Carolina and inspired the design of the Empire State Building in New York City.

(Photo Courtesy of Forsyth County Public Library Photograph Collection)

his bold leap, called Wake Downtown, is multifaceted and compatible with the aptly named Innovation Quarter.

Wake Downtown will extend undergraduate classes into the heart of Winston-Salem’s urban environment while keeping the umbilical cord to the Reynolda Campus through shuttles and other precision logistics.

Besides having undergraduate classes in a renovated tobacco building, the Wake Downtown initiative adds a Bachelor of Science degree in engineering, with the option of a concentration in biomedical engineering; a B.S. in biochemistry and molecular biology; and two new minors. One minor is in medicinal chemistry and drug discovery. The other, designed in consultation with the Wake Forest Institute for Regenerative Medicine, is biomaterial science and engineering, which focuses on how researchers can understand and mimic bone, muscle and soft tissues. These expanding disciplines will benefit from a partnership with the School of Medicine, which moved in July to a renovated tobacco building named the Bowman Gray Center for Medical Education, next door to what will become the undergraduate building.

Besides having undergraduate classes in a renovated tobacco building, the Wake Downtown initiative adds a Bachelor of Science degree in engineering, with the option of a concentration in biomedical engineering; a B.S. in biochemistry and molecular biology; and two new minors. One minor is in medicinal chemistry and drug discovery. The other, designed in consultation with the Wake Forest Institute for Regenerative Medicine, is biomaterial science and engineering, which focuses on how researchers can understand and mimic bone, muscle and soft tissues. These expanding disciplines will benefit from a partnership with the School of Medicine, which moved in July to a renovated tobacco building named the Bowman Gray Center for Medical Education, next door to what will become the undergraduate building.

The biochemistry/molecular biology major will begin in January, as will the new minors. The engineering major will begin next fall semester. By 2021, about 350 undergraduates are expected to be studying downtown in the new programs. That would move undergraduate enrollment, currently about 4,800, closer to the expanded cap of 5,300 set by University trustees in April 2015.

Administrators expect students to find the proposals — and the setting — appealing. “All of a sudden, in a way, Wake Forest has taken a central piece of ourselves … and located it in the heart of downtown in a more edgy urban environment,” Kersh said. “We know that will appeal to a number of our students and possibly to applicants who haven’t come to Wake Forest because it was a little too bucolic.”

In this former manufacturing complex, the new undergraduate building will share an entrance and lobby with the Bowman Gray Center, which will house 70 full-time medical school faculty and staff. An additional 190 of the medical school’s 1,200 faculty members will teach there at times, depending on the curriculum. Much of the faculty will continue to work at the medical center campus on “Hawthorne Hill,” clinics and other facilities where medical students do hands-on training. Medical faculty will teach some of the undergraduate classes and share their laboratories, forging a medical-liberal arts coalition that administrators say is rare in higher education. The president has said it will bring the groups into “a durable, authentic programmatic collaboration.”

In this former manufacturing complex, the new undergraduate building will share an entrance and lobby with the Bowman Gray Center, which will house 70 full-time medical school faculty and staff. An additional 190 of the medical school’s 1,200 faculty members will teach there at times, depending on the curriculum. Much of the faculty will continue to work at the medical center campus on “Hawthorne Hill,” clinics and other facilities where medical students do hands-on training. Medical faculty will teach some of the undergraduate classes and share their laboratories, forging a medical-liberal arts coalition that administrators say is rare in higher education. The president has said it will bring the groups into “a durable, authentic programmatic collaboration.”

From coffee shops where students study to restaurants for al fresco dining along Fourth Street, the roads to Innovation Quarter offer a vibrant street scene in a city rebuilding its economy.

In another rare approach in the academic world, Wake Downtown will infuse its engineering and biomedical programs with the University’s signature liberal arts education model and face-to-face engagement with faculty in small classes.

Only a handful of schools combine liberal arts intensively with engineering, among them Harvey Mudd College in Claremont, California, Smith College in Northampton, Massachusetts, Swarthmore College in Swarthmore, Pennsylvania, and Bucknell University in Lewisburg, Pennsylvania, according to Kersh. A few schools, including Johns Hopkins and Stanford universities, have medical school faculty who teach undergraduate courses.

“We may well be the only school that has both an engineering program rooted in the liberal arts inside a college and has medical school faculty partnering, helping shape it and teaching it. We think it’s the best of both,” Kersh said. Engineering and science majors won’t be the only ones coming into the city core. The University expects to offer additional undergraduate classes next year. Possibilities include entrepreneurship, bioethics, public health policy, the humanities and the arts.

“We don’t see this as just being an enclave for scientists but an extension of the campus as a whole,” Gillespie said.

Hatch said the University has a history of looking for ways to improve and “play above its weight.” With heightened interest from the medical school in collaborating with Reynolda Campus and the “magic sauce” of tax credits and space downtown, the faculty and staff saw an opportunity, Hatch said.

Hatch said the University has a history of looking for ways to improve and “play above its weight.” With heightened interest from the medical school in collaborating with Reynolda Campus and the “magic sauce” of tax credits and space downtown, the faculty and staff saw an opportunity, Hatch said.

“In recent years, we’ve talked about Wake Forest being radically traditional and radically innovative,” Hatch said. “I think we’re very traditional in our core mission of excellent academic programs that are very student-focused. At the same time, I think we need to be highly original and innovative about how we go about that. We’re poised to look for opportunities that can enhance and expand who we are. This is the latest.”

Donna Boswell, chair of the University’s Board of Trustees: “It’s going to be very fun for students to have a broader oyster, so to speak, from which to build their Wake Forest education.”

onna Boswell (’72, MA ’74), chair of the Board of Trustees, has watched the idea unfold through the lens of her background in health care law. She lives in Winston-Salem and recently retired as a partner in the Health Group of the law firm Hogan Lovells US LLP, where she advised hospitals, academic medical centers, research companies and manufacturers on compliance issues. Before that, she was a professor at Wesleyan University.

“We’re trying to do it differently than if we were to build another building and plop it down on campus,” Boswell said. “We’re very focused on synergies with faculty, the medical school, business and potential startups. That synergy will be just phenomenal for our students.”

Students, faculty and researchers will be able to take advantage of a tenet of Innovation Quarter, that proximity leads to collaboration — that, indeed, “what if” conversations can lead to “wow” ideas.