CHARLOTTE – When the Lost Boys of Sudan fled for their lives, away from torched huts and murdered parents, dodging government militia from Khartoum, swimming deep underwater to avoid the unblinking gaze of crocodiles, inching past lions in thorn-tree scrublands and suffering such thirst that at times urine sufficed for water, Phillips Bragg (’93) knew nothing of their plight. He finds it astonishing that in 1991 he was busy choosing his English major at Wake Forest while Lost Boy James Lubo Mijak was struggling to survive in a southern Sudan camp for displaced persons called Pochalla.

To this day Phillips has never been to Africa. But for him to ignore Sudan is unthinkable now. Lubo brought Africa and its injustices to him. “He’s like a brother. I’ve known him for a decade, probably spent more time with him outside of my family than with anyone else,” Phillips says. For all practical purposes, Lubo has become family, a gentle presence frequently at the Braggs’ farm in Huntersville, N.C. “He’s enriching our lives. What he’s giving to our children is way beyond what we’re giving,” says Phillips’ wife, Leslie McLean Bragg (’91).

Together they aim to fulfill Lubo’s dream of building permanent primary schools in southern Sudan. “From education comes wisdom,” Lubo says, “and from wisdom comes peace.” And with the help of Wake Forest alumni and parents inspired by the Braggs in this, the 10th anniversary of the Lost Boys’ arrival in the United States, the dream called Raising Sudan is becoming a reality.

A country one-quarter the size of the United States and marked by the Nile River and its tributaries, Sudan has known little peace since its independence from Britain in 1956. Two civil wars followed, the most recent from 1983 to 2005, ending thanks to a peace agreement and the promise of a referendum. In January southern Sudanese voted to secede. The Republic of South Sudan, where Lubo and the Braggs have set their sights, is due to become independent and the world’s newest country on July 9.

In the second civil war, an estimated 2 million people died and 4 million were displaced as violence raged between the mostly Arab and Muslim government forces in the north and separatists in the south, where Christianity and tribal religions prevail.

Lubo became one of the displaced, one of the 30,000 Lost Boys named after the band of orphans from “Peter Pan.” The first attack on his village, Nyarweng, in southern Sudan, came in 1984. Soldiers marauded and confiscated some of his family’s livestock. It was his childhood duty as a youngster to tend his father’s cattle, 334 sheep and 37 goats. When the final attack came, in 1987, he left his village and the remaining flock behind, running for his life, never again to see his parents. Eventually he came upon a procession of other desperate orphans and displaced people. They trekked hundreds of miles to camps in Ethiopia, southern Sudan and Kenya, ever on the run from war, with no one to call brother but each other.

“Lion attacks. Crocodiles. Disease. Most of the Lost Boys lost their lives,” Lubo told a reporter for NBA TV last year. He regards Pochalla as the worst camp, where he and the other children fended for themselves, surviving on some days by eating roots and leaves. It was a year later, in 1992, that the orphans evacuated to Kenya, becoming “refugees” in the eyes of the United Nations and able to receive rations from the international community. It was in Kakuma Refugee Camp in Kenya where Lubo “learned under the trees” in class and began dreaming about establishing a school in his village. “When you go to school you learn,” says Lubo. “You know the value of others and the value of everything — how to be respectful and to serve other people.”

At Kakuma after an exam and interviews, Lubo became one of 3,800 Lost Boys whom the U.S. government invited to resettle across the country, from Fargo, N.D., to Boston and places in-between. The process granted Lubo an official birthday — Jan. 1, 1982 — because the actual date is unknown, but Lubo thinks it’s closer to 1979 or 1980. At the assigned age of 19 in June 2001, Lubo made his way to Charlotte and, eventually, to the Braggs.

Left to Right: Claude (9), Leslie, Lubo, Phillips, John (5), Kirby (11) and, in front, Ernie the dog.

It was Martha Kearse, now minister to children and families at St. John’s Baptist Church in Charlotte, who noticed the gangling young men in Harris Teeter with “big bags of chicken legs” and “huge bags of rice” in their carts. “They were clearly African, and they were also completely lost,” she says. With purpose she complimented one on his wildly colorful African shirt — she wanted to help them check out — and then invited them to her church. “I had been reading about them in The New York Times Magazine,” she says. “I just remember thinking, ‘Bless their hearts to have moved from Kenya to Fargo.’” Or to Charlotte.

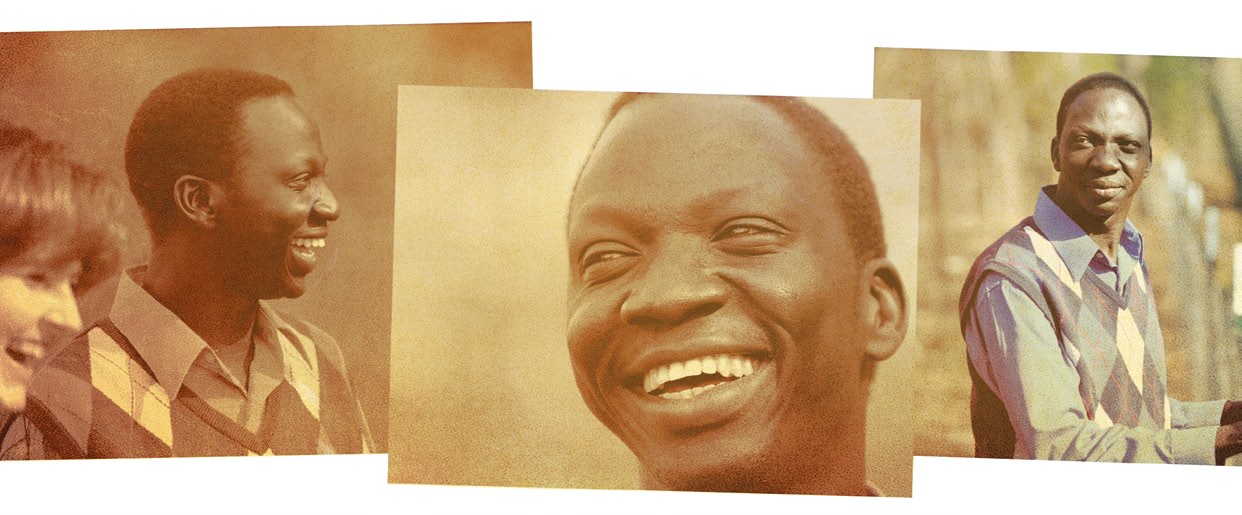

Lubo remembers the ride from the airport when he strained to no avail to see the tops of high-rises Uptown. “Wow, this is the home,” Lubo remembers thinking. The food was different from his simple fried bread and beans: “Everything was salty; everything was sweet.” On the day in February when we meet, Lubo appears thin, soft-spoken, quick to flash a smile broad as a moonbeam despite bleak memories. He wears a pressed red-striped shirt and black dress shoes polished to a gleam that matches his skin. He recalls his first Charlotte home. It was mysterious, potentially dangerous: “We were told ‘Be careful of electricity. When you are bitten by electricity, you might be shocked and killed.’ We were scared. Electricity was everywhere in the apartment.” Church friends later calmed the Lost Boys by explaining how the electric wires aren’t exposed. “It’s not wireless,” they told them.

While Lubo wasn’t among the grocery shoppers, he did become one of the 47 Sudanese faithful at St. John’s. Members there were quick to lend a hand. Carl Phillips (’56) and his wife, Nina, were retirees — they had owned an equipment rental/special events business — with time to spare and love to give. They mentored the refugees, created a scholarship fund and opened their home as a gathering spot and computer training ground for the young men. They are lauded as exemplary volunteers, but Carl downplays the notion. “When you know the story, it’s just hard not to help.”

When the church call went out for mentors one Sunday, Leslie and Phillips Bragg simply looked at each other in the sanctuary and agreed. “There was no need to debate it,” says Leslie, an assistant teacher in a ninth-grade English class in Davidson. At the time a stay-at-home mom, she and Phillips, a wealth manager at his family’s firm, Bragg Financial Advisors Inc., did not hesitate.

They, too, minimize how much they helped the independent Lubo. They gave him lifts to community college on rainy days, taught him to cook (his favorite is soup), taught him to drive (a harrowing undertaking) and coached him on navigating America’s distinctly complicated terrain — the DMV and insurance forms. Lubo succeeded at Central Piedmont Community College and at UNC Charlotte, where he earned a bachelor’s degree. He works two jobs, one as an assistant to the portfolio manager at the family’s investment management firm, founded by Frank Bragg (’61), Phillips’ father, and at Presbyterian Hospital, where he sterilizes surgical equipment.

Lubo credits Phillips with guiding him “to prepare me to be a good citizen with the love of this country.” He is now an American citizen with an appreciation for the “very wonderful” Bragg family of parents, siblings and in-laws (with 11 Wake Forest degrees among the immediate family) “whereby everybody sticks together.” Frank Bragg, the patriarch (P ’88, ’90 and ’93), says, Raising Sudan “fits with our philosophy to do whatever we can to make it a better world.”

Phillips, who turns 40 in August, tells his buddies, “Don’t throw me a party. Build me a school!” (Here with son John and Lubo at the Huntersville farm.)

Lubo says, “In the African culture if somebody worry about you, care about you … he’s a good friend; he’s a brother.” Of Phillips and Leslie, he says, “I have been a witness to their care and love since I came.” Leslie’s memories of Lubo are of his being “shy and gentle and smiling from day one” and especially caring and playful with the Braggs’ three little boys. “It could be a glimpse of how children were treated in his village,” she says.

The Raising Sudan project arose from Lubo’s first visits home in 2007 and 2008 to talk with villagers about their needs. Food. Medicine. Clean water. The list was daunting, but education was prized above all. Lubo was prepared to live up to his name, which means “responsibility.” He returned to find the Braggs ready to help with the cause.

Phillips enlisted the expertise of Mothering Across Continents, a Charlotte nonprofit that works as a catalyst shepherding dream projects that can serve as sustainable global models for change. The goal: two schools to serve 300 children apiece with four classrooms, eight latrines, teacher accommodations, a water source, a kitchen, desks and equipment for a total of $375,000. “Nothing crazy. Just solid and permanent structures with well-trained teachers,” the Braggs and Lubo wrote in their first fundraising letter last summer. On many of the letters addressed to friends from Leslie’s Christmas card list Phillips added two handwritten words in closing. “‘Pro Humanitate,’” he tells me, “knowing they would know exactly what I meant: ‘If not us, then who?’”

Patricia Shafer, founder and head of Mothering Across Continents, says building in a post-conflict society in a remote location without infrastructure is “like building on the moon.” But Phillips has been “strategic” and “relentless in the best sense of the word” in pursuing the dream of Raising Sudan. “Here is where the light of Phillips shines,” she says. “If he is not an example of Pro Humanitate, I don’t know who is.”

By mid-March construction was under way for the school in Lubo’s village, with $160,000 raised toward school construction with the goal to complete the buildings before the rainy season begins this summer. Phillips has been the most active individual fundraiser for Raising Sudan, and his fellow Wake Foresters have answered his and Leslie’s call: Of the money Phillips has raised, more than 50 percent has come from members of the Wake Forest alumni community. The quest is about more than money for the schools, Phillips adds. It’s about “momentum,” providing a model for other Lost Boys to duplicate, and it’s a gift for Lubo, who now has a family in his homeland after marrying and becoming a father of twins.

“The upside is enormous in this brand new country, and further, without the right investment in education right now the downside is enormous. This is the time to feed the fire of education, peace, reconciliation, democracy,” Phillips says. “This is our village. These kids belong to all of us in Charlotte and to everyone. I’m going to see that their school is built.”

To learn more, see the motheringacrosscontinents website.