Destruction in Asheville, North Carolina. Photo/BeLoved Asheville

I’m obsessed.

Like many in my new hometown of Asheville, North Carolina, the question dogging me since Hurricane Helene is: When will we get clean water back?

While I’m beyond grateful Helene did not damage the home that my husband, three cats and I moved into on May 31 to escape the Austin, Texas, increasingly hot summers — hah! — seeing the devastated neighborhoods, infrastructure and lives is wrenching. And personal. This has been the longest six weeks of my life. I mark milestones in deficits:

Twelve days without power.

Nineteen days without a flushing toilet.

Twenty-three days without internet.

One hundred and two deaths.

And six weeks — and counting — without clean water.

Photo/N.C. Department of Transportation

It’s wonderful having neighbors who look after one another, but the lack of clean water has been hard on us all. Now that we have city water, we can finally flush toilets without hauling buckets from neighbors’ ponds and hot tubs. The West would not have been won had I been on the wagon train.

Mary Ann Roser, Asheville resident

Meanwhile, government officials and infrastructure workers have been trying mightily to restore Asheville’s water system, but it was so damaged it must be rebuilt. Now they are trying to reduce sediment with giant curtains. That appears to be helping, but there’s no date certain for drinking water.

Emergency personnel respond after the floods in Western N.C. Photo/Asheville Police Department

Meanwhile, we’re told not to drink the reservoir water that’s been heavily treated with aluminum sulfate and caustic soda. That also means no cooking with it or brushing teeth, either, and many of us — me included — won’t wash our bodies, clothes or dishes with it. Some neighbors have described skin breakouts from showering, brown streaks on dishwasher-sanitized glasses and ruined clothes from washing machines. Thanks, but I’ll wait.

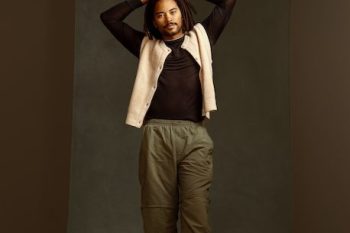

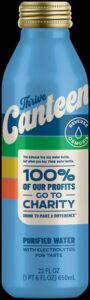

I told all of this to alumna Lindsay Chambers (’00) of Los Angeles (Malibu) when we recently chatted on Zoom about our shared obsession. As the founder and CEO of two nonprofits she created in 2023 and seeded with $5 million of her own money, Chambers donated 42,000 reusable, recyclable water-filled aluminum canteens to Asheville and 100 reverse-osmosis water filtration systems. Residents were touched to receive $300 filtration units, she says, and the canteens were a hit with young and old.

Thrive Canteen distribution in Western N.C. Photo/Together We Thrive

Chambers’ two nonprofits, Together We Thrive and Thrive Canteen, are all about bringing clean water to those who need it. They were here for us when we were reeling.

“Water is the cornerstone of life,” says Chambers, who earned a bachelor’s degree in history from Wake Forest and a master’s degree in history from Stanford University in 2008, and she recently served on the Wake Forest Board of Trustees. What has happened here, she says, “is far and away the biggest water disaster in the United States.”

“Water is the cornerstone of life,” says Chambers, who earned a bachelor’s degree in history from Wake Forest and a master’s degree in history from Stanford University in 2008, and she recently served on the Wake Forest Board of Trustees. What has happened here, she says, “is far and away the biggest water disaster in the United States.”

Chambers was visiting her grandmother in Florida when Helene struck. “I immediately wanted to help,” she says. “There are a lot of organizations that help bring clean water to third world countries, but the reality is, we have contaminated water right here in the United States, and it’s largely ignored.”

Lindsay Chambers ('00), CEO and Founder of Together We Thrive and Thrive Canteen. Photo/Together We Thrive

Both of Chambers’ parents are natives of West Virginia, and they grappled with contaminated water from deteriorating plumbing and coal mine run-off, she says. “It’s really stressful not being able to use the water out of your faucets.”

A successful designer and real estate developer with a growing interest in green building and carbon-neutral housing, Chambers received Wake Forest’s Excellence in Entrepreneurship Award in 2017 and had an epiphany in 2022 that changed her life.

“We are warming faster than we should be, and if we don’t stop this, then the world is not going to be a hospitable place to live in, and a lot of people are going to die,” she says.

Thrive Canteen distribution in Western N.C. Photo/Together We Thrive

That led her to seek more fulfilling work, doing what she loves, she says: “Helping people and teaching people … how to live in the world without making it warmer.”

She quickly adds that she understood “no one is going to listen to an interior designer and real estate developer. … That’s when I decided to build myself a seat at the table. I realize there (are) going to be more and more extreme weather events, and Asheville is proof that there is nowhere safe from extreme weather.”

Amen to all that.

My husband and I consider ourselves climate-change refugees. We knew we couldn’t outrun it by leaving Austin, but we did not expect a hurricane in Asheville, which is over 2,100 feet above sea level and some 300 miles from the coast. Nor did I ever expect to live anywhere — for weeks on end — without being able to drink from the faucet. I think of all the water I’ve wasted over the years, merrily letting the faucet run while I brushed my teeth, filling the bathtub to the brim, watering the dadgum lawn.

My husband and I consider ourselves climate-change refugees. We knew we couldn’t outrun it by leaving Austin, but we did not expect a hurricane in Asheville, which is over 2,100 feet above sea level and some 300 miles from the coast. Nor did I ever expect to live anywhere — for weeks on end — without being able to drink from the faucet. I think of all the water I’ve wasted over the years, merrily letting the faucet run while I brushed my teeth, filling the bathtub to the brim, watering the dadgum lawn.

After Helene, businesses were shuttered because no one had water or power, and supplies couldn’t reach us because of washed away roads and downed trees blocking access.

Destroyed roads in Asheville, NC. Photo/N.C. Department of Transportation

At my house, we had a case of small bottles of water left over from a party. It went fast. When we were down to seven bottles, I thought we could stretch them out two more days. I put pans outside to catch rainwater. Thankfully, bottled water from the government and donations started to pour in, including from Chambers’ organizations.

Asked if her time at Wake Forest influenced her work, Chambers says, “Wake Forest attracts students who want to give back to humanity.” She is proud that the University is involved in hurricane relief.

Wake Forest is collecting donations through Thursday to support Second Harvest Food Bank and will host a Community Day of Action for hurricane relief Saturday. Athletics will direct a portion of ticket proceeds.

Photo/Together We Thrive

I love that Thrive’s canteens are not adding to the mountains of plastic we have generated during this disaster.

“I want to encourage people to consume more mindfully and think about what they’re buying and how it affects the world we live in and climate change,” Chambers says. “I want to spark an ethical consumer movement.”

Thanks to the kindness of strangers like Chambers, Asheville will get past Helene’s devastation. And I believe we will, indeed, thrive.

Editor’s update for 11/18/24: Fifty-three days after the storm, Asheville notified residents that the water coming out of faucets was clean enough to drink. The announcement elicited excitement on social media and comforted people who had been expecting there might not be clean drinking water until sometime in December.

Mary Ann Roser is founder and chief of Roser Prose LLC, which does writing, editing and communications consulting. She was a daily newspaper journalist for more than 30 years. When she lived in Texas, she wrote this story for Wake Forest Magazine about Eric Olson (’77, Ph.D. ’81, DSc ’03), an acclaimed scientist in Dallas using CRISPR technology and a winner of Wake Forest’s Distinguished Alumni Award in 2020.