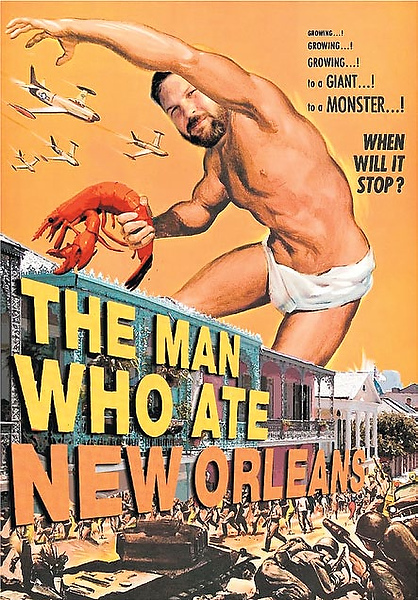

A prototype movie poster proclaims: “Never since King Kong such a mighty appetite!” As New Orleanians might ask, “Who dat?”

He’s none other than Ray Cannata (’90), perhaps the most unlikely Presbyterian minister you’ll ever meet and the man eating his way through every bistro, café, deli, grill, tavern and joint in New Orleans — all 750 of them. For Ray Cannata, life’s a Mardi Foie Gras.

The upcoming documentary “The Man Who Ate New Orleans” is his story. It describes Cannata’s unstoppable journey through piles of real ’Nawlins food — po boys, gumbo, turtle soup, muffuletta, and his personal favorite, oysters.

There was no stopping Ray Cannata once he began eating his way through every bistro, cafe, deli, grill, tavern and joint in New Orleans.

“It wasn’t exactly hard work,” Cannata admits. Instead, it was a joyful pilgrimage to get to know the people of New Orleans and help rebuild a great American city nearly destroyed by Hurricane Katrina six years ago.

“To understand New Orleans, you have to understand the food,” says Cannata, a native of New York who arrived from New Jersey in January 2006, four months after the hurricane battered the levees. “When I moved here, I almost immediately fell in love with the city. To understand the culture and the subcultures, I needed to start at the table. You hit every table in New Orleans, and you’ll hit every story in New Orleans.”

He, his wife, Kathy Fortier Cannata (’89), and their two children, Andrew, now 12, and Rachel, 8, moved when Cannata was named senior pastor of Redeemer Presbyterian Church, worshipping then and now in another church’s building on St. Charles Avenue. Under Cannata’s direction the congregation of 17 — now 180 — focused on connecting with the community and rebuilding houses. Over the last five years, thousands of volunteers from across the country have helped his church rebuild some 500 homes and counting.

“We have one service, and we build houses,” Cannata says. “Obedience to the Bible drives me to try to be a good neighbor and to want to see our hood and our city transformed, celebrated and renewed.”

Kathy Cannata says her husband never does anything in moderation. Which explains why his mission to learn his new city through a gastronomic odyssey grew out of control, leading him to become the only person ever to eat at every single non-chain restaurant in the Crescent City. The goal was ever-changing since New Orleans counts about two new restaurant openings a week, pushing the initial goal of 500 restaurants up by 250.

“The Man Who Ate New Orleans” serves up tales of the people, food, music and culture that Ray Cannata discovered during his gastronomic journey to embrace his new hometown.

“Being a minister certainly hasn’t stopped him from enjoying life to the fullest,” Kathy Cannata says. Once he decided to eat at every restaurant, “I had no doubt that he would finish it.”

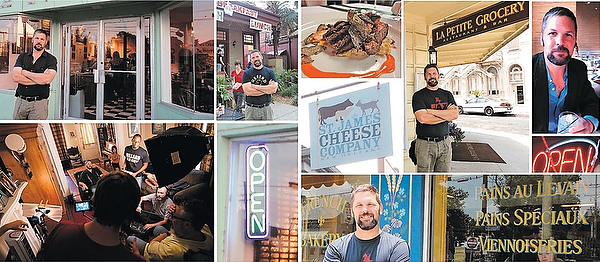

Cannata tells many of the stories from his journey — of food, music, culture, race relations, the rebuilding of the city — in the documentary, produced and directed by Michael Dunaway for Gasoline Films. The film, expected to be released in fall of 2012, counts Academy Award-nominated director Morgan Spurlock of “Supersize Me” fame as an adviser. Some of the film’s proceeds will go to the home-building program at Cannata’s church.

The film — thankfully — doesn’t include all 750 restaurants. In one scene at Willie Mae’s Scotch House in the Seventh Ward, Cannata has some fried chicken with chef John Currence, owner of City Grocery in Oxford, Miss., and son of Becky and Dick Currence, both in the Class of ’61 and residents of New Orleans. They discuss Currence’s efforts to rebuild Willie Mae’s, and Cannata judges the fare “the best fried chicken in America.”

“What I love about the guy,” Currence says later, “is when he moved here, he embraced the entire city in his grasp. I’m magnetized by his passion for both his ministry and his love of New Orleans. He genuinely feels that he can hug the city and make a difference.”

At Jacques-Imo’s Café in Carrollton, Cannata sits at a table in the back of an old pickup truck, with “real ’Nawlins food” painted on the side, while chef Jacques Leonardi serves up fried green tomatoes with shrimp remoulade, carpetbagger steak and cornbread, while he and Cannata discuss food and music. Cannata pronounces it “the best cornbread in America.”

At Dooky Chase in the Seventh Ward, Cannata enjoys gumbo z’herbes — “the best gumbo in the city” — with owner and prominent African-American female chef Leah Chase while exploring the history of the Civil Rights Movement in New Orleans.

After realizing that he’s describing every meal as “the best in … ,” Cannata pauses his rapid-fire culinary reviews to acknowledge, “I have a habit of saying that, but a lot of people agree with me.”

He should know after eating in every restaurant in the city, from Commander’s Palace in the Garden District to Juan’s Flying Burrito in the Lower Garden District and McKenzie’s Chicken-in-a-Box in Gentilly, to places with walk-up windows and signs out front proclaiming “Breakfast all day” or “catfish” hand-painted on plywood, to hole-in-the-wall dives where he feared for his life.

He goes from extolling the virtues of a meal at Arnaud’s or Antoine’s, which can run up to $200 with wine, with stories about the 99-cent breakfast special at Miss Gloria’s (you’ll probably need three) and his favorite wing shack in the roughest part of town.

You would think the man who ate New Orleans would be the proverbial poster boy for Fat City. But not Cannata. After selling his car, he began walking and biking most everywhere. (Lunch in the French Quarter means an 11-mile roundtrip.) He cut out soft drinks and most sweets. In the last few years he has lost 10 pounds, making the man who ate New Orleans an inspiration to foodies everywhere.

Cannata, the newcomer who has grown to love his city and its hundreds of restaurants, is clear-eyed about his adopted New Orleans’ problems — crime, poverty, a failing school system, political corruption, the ever-present danger of flooding. “New Orleans is a balance between heaven and hell,” he says. “We need both in our lives — the heaven gives you things to enjoy and the hell gives you things to fix, a mission. It’s when all you have is the in-between, the lukewarm stuff, that you get bored and restless and end up kicking the dog.”

But in the next breath he says he can’t imagine living anywhere else. “Why did I wait 37 years to find a city that’s as crazy as I am?” he ponders. “When I was in New Jersey, I used to be the crazy one, now I’m the sanest guy here. It’s great to be in a town that appreciates uniqueness and quirkiness. If you’re not a little crazy, you don’t stay here.”

Ray Cannata shares his favorite joints for po boys, muffuletta, gumbo, turtle soup, country-fried steak and the “cheapest good eats” in New Orleans at magazine.wfu.edu