The two 1930s steamer trunks — “big enough to stow a body,” in the words of Sally Stallings — sat undisturbed for decades. After her mother’s death nine years ago, Stallings hauled the trunks to her home in Fresno, Calif., and stashed them in a far corner of her basement.

The two 1930s steamer trunks — “big enough to stow a body,” in the words of Sally Stallings — sat undisturbed for decades. After her mother’s death nine years ago, Stallings hauled the trunks to her home in Fresno, Calif., and stashed them in a far corner of her basement.

Two years ago, she decided it was time to discover what secrets the trunks held. The trunks had belonged to her father, the prominent novelist, playwright and screenwriter Laurence Stallings (1916) and had been sealed since his death in 1968.

Using a screwdriver to pry open the rusted latches, Stallings said she felt like Howard Carter discovering King Tut’s tomb. When she finally pried open the trunks, she discovered something more valuable to her than gold: a missing part of her past.

What she found compelled her down the road 100 years into her father’s and Wake Forest’s past and then back again when her father and his alma mater were reunited. Her journey ended at Wake Forest in March when she accepted the citation for Laurence Stallings’ induction into the new Wake Forest Writers Hall of Fame. “My father loved Wake Forest,” she says. “This was where it all began for him.”

***

Sally Stallings was 26 when her father died after suffering a heart attack. He was only 73, but she speculates that the physical and emotional scars he carried from World War I — and which he frequently revisited for some of his most prominent works — finally caught up with him. She speaks wistfully when she recalls his death; there were still so many questions left to ask, still so much that she didn’t know about him. “There was a feeling of incompleteness,” she says today.

She knew that her father, a native of Georgia, enrolled at Wake Forest in 1912. He was a classics major and editor of the Old Gold and Black. On the ceiling of his boarding-house room, above his bed, he posted a sign, “A champion would get up.” That would define him for the rest of his life, Sally Stallings said.

She knew that it was at Wake Forest where he met his first wife, Helen Purefoy Poteat, the daughter of William Louis Poteat, president of Wake Forest from 1905 to 1927. They had two daughters, Diana Poteat Stallings Hobby and Sylvia Stallings Lowe. After their divorce in the mid-1930s, Stallings married Louise St. Leger Vance, the voice of Fox Movietone newsreels.

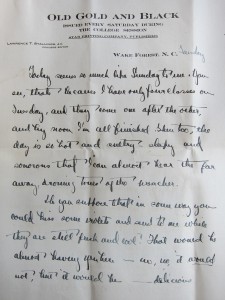

A letter Stallings wrote to Helen Poteat in 1916 on Old Gold and Black stationery. Historical images courtesy Special Collections and Archives, Z. Smith Reynolds Library.

Stallings joined the U.S. Marines in 1917 and was a “doughboy” in France in World War I. He received a Purple Heart after being severely injured while taking out a German machine gun position in the Battle of Belleau Wood in France; his right kneecap was blown away. (He would lose his right leg a few years later and eventually his other leg to an aneurysm.)

His 1925 autobiographical novel about his war experiences, “Plumes,” was later adapted into King Vidor’s film “The Big Parade.” His 1933 book, “The First World War — A Photographic History,” was regarded as one of the greatest pictorial histories of the war.

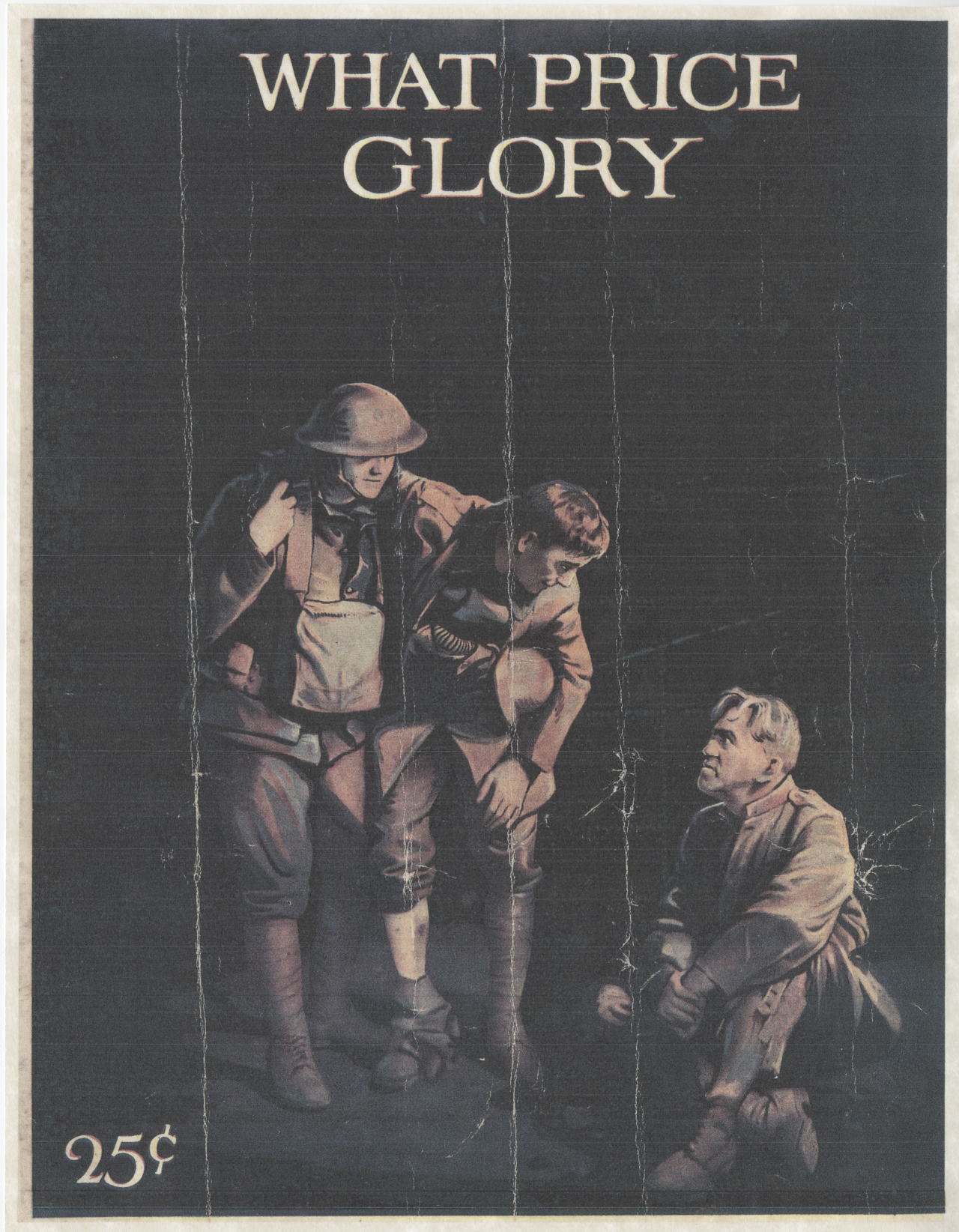

In the 1920s and ’30s, Stallings collaborated with some of the biggest names in Broadway and Hollywood. He wrote the acclaimed play “What Price Glory?” with Maxwell Anderson; adapted Ernest Hemingway’s “A Farewell to Arms” for the stage; co-wrote the theatrical production “Rainbow” with Oscar Hammerstein; and co-wrote the screenplay for John Ford’s “She Wore a Yellow Ribbon.”

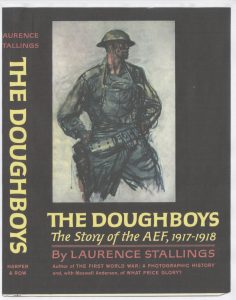

Sally Stallings was most familiar with his last, and perhaps finest, work, ”The Doughboys: The Story of the AEF, 1917-1918,” published five years before his death. He drew upon his own experiences to tell the gripping stories of the one million troops of the American Expeditionary Forces that poured into France in the final year of the war to repel German forces.

***

Sally Stallings knew all those things about her father, but there was still something missing. When she finally opened the steamer trunks, she found it. Inside was a treasure trove of the many lives her father lived.

There were love letters and notes from her father to her mother. There was a photograph of her father with two legs; she had never seen him with two legs. She realized that her talents as a visual artist — she is a retired art teacher — came from her father’s visual writing style. The pieces of her father’s life began to fall into place.

She discovered piles of drafts and gallery proofs from “The Doughboys” with her father’s handwritten corrections in black and red ink. There were letters from World War I veterans and maps that he drew depicting World War I battles. She was 20 again; she helped proof “The Doughboys” while home from college one summer. “Who would have thought that I would ever see those pages again,” she said 45 years later.

She dug deeper into the trunks. There were movie scripts written on onion-skin paper, dozens of short stories, book proofs, letters and unpublished manuscripts, in blue and green folders and battered envelopes and spiral notebooks. She found a shooting schedule for 1942’s “The Jungle Book” and a first draft of his screenplay for 1954’s “The Sun Shines Bright.”

She found her favorite movie script, “She Wore a Yellow Ribbon,” written by her father in 1949. She was eight again, wearing a yellow dress and new patent leather shoes, clunking loudly down the aisle at the film’s premier at a Palm Springs theater. She recalls the film’s star, John Wayne, bouncing her on his knees at a party at her parent’s house in Pacific Palisades, Calif., and tossing his wine glass into the backyard gold fish pond.

There were articles and stories on the war between Italy and Ethiopia that he covered with Fox Movietone news in the mid-1930s. There were letters and documents from his service in World War II, when he was recalled to the U.S. Marines and stationed in the Allied war room in London.

Sally Stallings knew there was no shoving the trunks back to the dark corners of her basement. She and her brother, Laurence Jr., have donated the collection to the Z. Smith Reynolds Library, where it will be available to historians and students. Wake Forest is the proper home for her father’s papers, she said. “I feel like they’re finally home.”

She spent a year going through the trunks and cataloging every scrap of paper. As she was boxing up the collection to send to the library, she made another discovery: there was already a Stallings collection in the library. In 2008, her half-sisters, Diana Poteat Stallings Hobby and Sylvia Stallings Lowe, had donated their own collection of their father’s works.

That collection largely includes papers and documents from the first half of Stallings’ life: letters from his first wife, Helen Poteat, and father-in-law, William Louis Poteat; correspondence from playwright Paul Green and authors Ernest Hemingway and William Faulkner; and reviews of his earlier novels, films and plays.

Sally Stallings had never met — or even talked to — Hobby or Lowe, until she picked up the phone last fall and called Lowe, who lives in Alexandria, Va. Hobby and Lowe invited Stallings and her brother to meet them at the Poteat ancestral home, Forest Home, in Caswell County, North Carolina. Laurence Stallings lived there during his marriage to Helen Poteat and wrote many of his earliest works there.

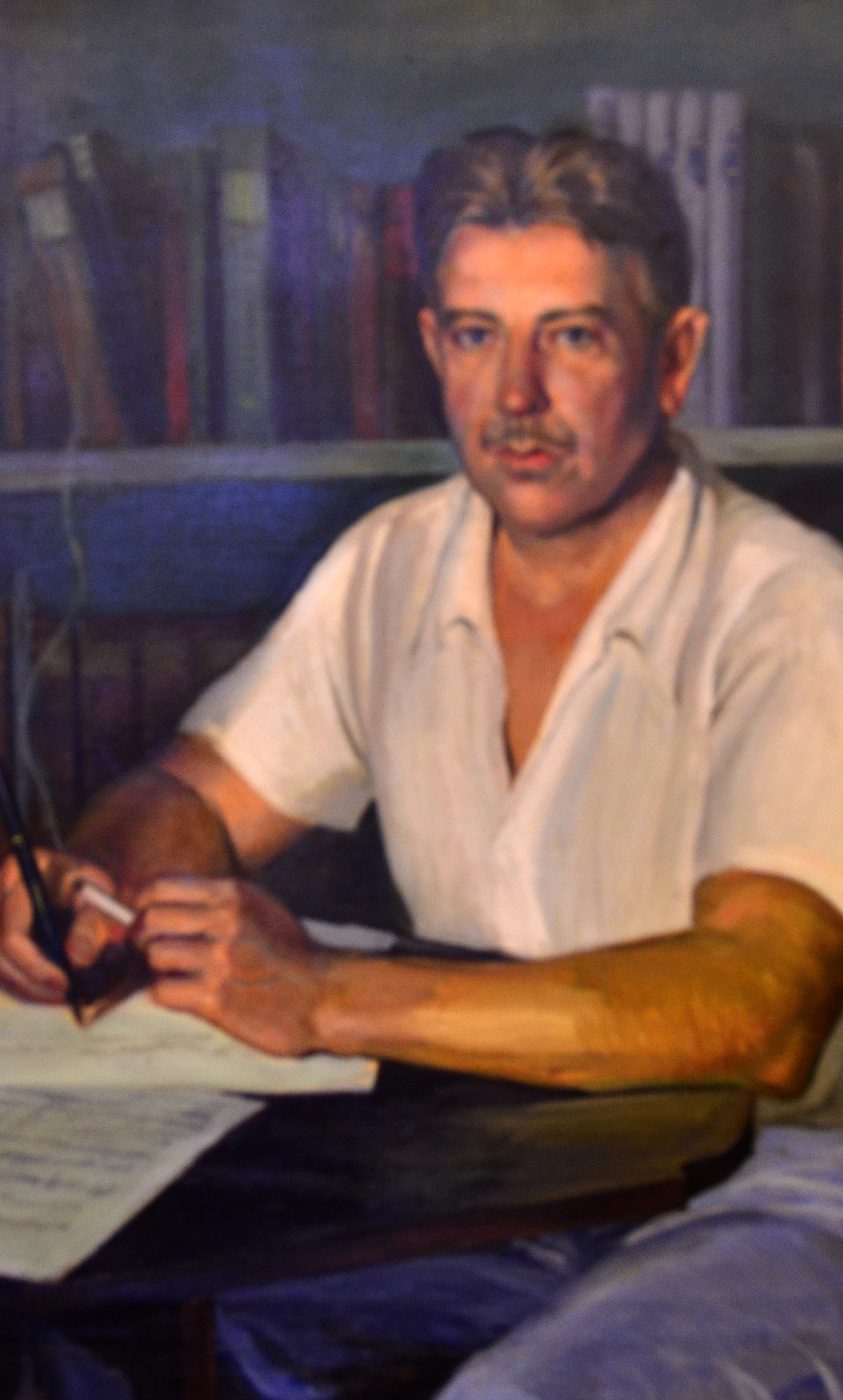

Sally Stallings and her youngest son, Ronald, with a portrait of Laurence Stallings in the Z. Smith Reynolds Library.

Stallings and her brother also made their first trip to Wake Forest. They saw, for the first time, in the Z. Smith Reynolds Library a portrait of a young Laurence Stallings posing in the library at Forest Home. They also visited the Old Campus, where their father was a student 100 years ago.

Sally Stallings’ journey that had started in the darkest corner of her basement in Fresno, Calif., had ended across the country. “I gained a home for dad’s papers, gained knowledge and friendship of two half-sisters, and saw some of my dad’s roots here,” she said. “It’s closed some circles in my life.”