Wake Forest wasn’t exactly a hotbed of student activism that was roiling other college campuses in the 1960s and early ’70s. But one spring night in 1970, about 600 students marched arm-in-arm up Wake Forest Road to President James Ralph Scales’ home to demand an end to the Vietnam War — and the cancellation of final exams so students could work for peace.

Anti-war sentiment had been building on campus over the year. Students had organized a “Vietnam Moratorium Committee” to sponsor protests and meetings, marched in downtown Winston-Salem, held a “Convocation for Peace” and protested at the Selective Service office in downtown Winston-Salem. At an ROTC program on campus, some students placed flowers in rifles held by their classmates.

The anti-war sentiment on campus was strong, but not universal, two of the protesters, Kirk Fuller (’73, MA ’75) and George Bryan (’72), recalled in interviews in 2012. It was a time for male students when your birthday could get you sent straight to Vietnam if you were unlucky enough to have a low lottery number. Fuller did, but had joined the Navy Reserves to delay active duty.

Bryan, son of the late religion professor G. McLeod Bryan (1927), was a conscientious objector. He said he always found it frustrating that students seemed more interested in intervisitation – allowing male and female students to visit in one another’s rooms — than with ending the war.

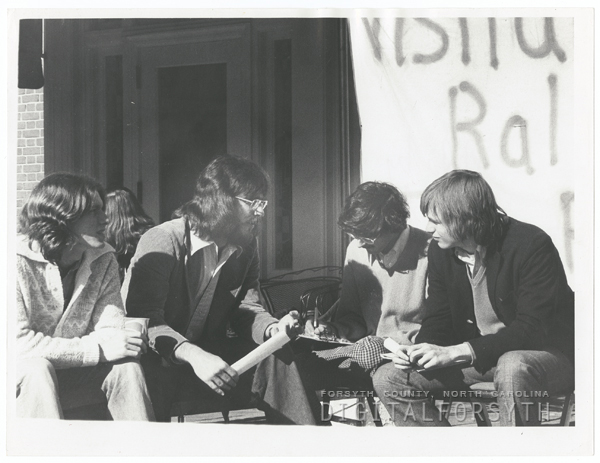

But following the U.S. invasion of Cambodia and the killing of four students at Kent State University by National Guardsmen, about 400 students gathered for an anti-war rally in front of Wait Chapel on May 19, 1970.

Fuller, then a junior, read a list of 19 demands calling for an end to the war and addressing a variety of campus grievances.

After a student suggested a march to Scales’ house to present the demands, students ran through the dormitories and the library encouraging others to join them. About 200 more students joined, whether out of true convictions against the war, or to join the excitement, or because they wanted exams cancelled so they could head to the beach.

As students settled onto the lawn at Scales’ house – now Starling Hall – Fuller read the list of demands and warned of a student strike until all classes and final examinations were cancelled. The rest of the semester should be devoted to “independent thought and discussion of the problems confronting our society … we want answers not found in the classrooms of Wake Forest.”

Students demanded that Scales:

• Call for the immediate withdrawal of troops from Southeast Asia;

• End contracts with companies involved in the war effort and “genocide against Black Americans; ”

• Abolish the campus ROTC program;

• End discrimination against black cafeteria workers;

• Fire the campus police chief and disarm the “incompetent and devious” campus police;

• Approve intervisitation to allow male and female students to visit in one another’s rooms;

• Improve student health care;

• Establish a day-care center for faculty and staff;

• Give students two-weeks off from school to work for candidates in the 1970 election.

And for good measure, they called for Reynolda Gardens to be open all day long. “It was a group effort – pretty much anything anyone wanted,” Fuller says today. They never really expected Scales to agree to their demands, he says, but it didn’t hurt to ask.

Scales came out of his house and invited Fuller and several other students inside for coffee. When they reemerged 30 minutes later, many students had already lost interest and left. Scales told the students he understood their goals, but deplored their tactics. “I’ve been proud of Wake Forest students many, many times, but this is not one of those times,” he said. He went back inside his house, and students returned to their dorms and the library to study for final exams.

Then-Provost Edwin G. Wilson (’43) and other faculty members met with students in Reynolda Hall to help calm things down and encouraged them that any further protests should be peaceful and non threatening. Students called off the planned strike.

Tyler Stone (’97), who wrote a history seminar paper on the anti-war protests, “Pro Humanitate, Anti War: A distinct Wake Forest observance of the Vietnam Conflict, 1969-71,” noted the significance of the peaceful nature of the protest, when protests at so many other schools turned violent. “After the president’s rebuttal, there was no further action despite the ease through which students could have caused disruption. The fact that students remained civil and dispersed in an orderly and peaceful manner is a testament to the nature of the protest movement at Wake Forest.”

Fuller and Bryan credit the close relationship that students had with Scales, faculty members and even the campus police with keeping the march and other anti-war protests civil and peaceful. Some faculty members supported the protests, and even Scales was known to be sympathetic to the students’ efforts. Following the Kent State killings, Scales sent President Richard Nixon a telegram protesting the killings and approved Student Government’s request to cancel classes for one day.

But some faculty members didn’t approve of the protest. The University Senate later condemned the march: “Discussions regarding crucial and substantive issues … will not be resolved on the president’s lawn at night in an atmosphere of rancor.”

The Old Gold and Black had a different take, hailing the march as a positive sign that students were becoming more concerned with events both on and off “this Garden of Eden campus.” The OG&B boldly proclaimed that Wake Forest “will never again be the nice, quiet school it once was.”

In reality, the event faded quickly with the end of the semester. Within days, Fuller – who like Bryan was the son of an alumnus, Fleming Fuller (’32, MD ’34) — was called to active duty in the U.S. Navy. He spent the next two years in the Navy before returning to Wake Forest on the GI Bill and earning his undergraduate and graduate degrees in history. Today, he’s a senior representative with Mutual of Omaha in Cary, N.C.

Bryan was elected Student Government vice president the following year after running on a peace platform. He later worked with gangs and youth in the South Bronx before returning to Winston-Salem to work with children and youth.

Bryan says the march and other events helped change opinions about the war. “Doing events like the rallies helped mobilize a number of students as to what was occurring in other parts of the world and influenced what they studied and how they looked at the world,” he says. “It brought more students around (to the anti-war effort), and I’m sure it brought more professors around. You couldn’t be isolated anymore and just deal with academics.”

Several weeks after the march, on Memorial Day, students placed a thousand tiny wooden crosses in a field along Polo Road, each cross bearing the name of a North Carolina soldier killed in Vietnam.

Students put up crosses honoring those killed in Vietnam.