Winding down narrow North Carolina country roads, A. Elizabeth Watson (’74) does not see cows and gas stations, cellphone towers and silos. She observes history — living, preserved and forgotten. More than that, Watson sees possibility.

Part historian, part environmental expert, part planner and part preservationist, Watson is the woman behind some of America’s most cherished landscapes. A principal consultant at Heritage Strategies, she lives in Chestertown, Md., on the Eastern Shore; she travels to sites, cities and entire regions across America to unite the land with the people living on it, unearthing historical narrative in the process. More than a job, this “placemaking,” as Watson describes it, is a way to make sense of and thrive in the world and the spots we call home.

“Communities that use placemaking techniques and understand their history are better able to present themselves in what’s basically a new economic world order,” Watson says, “where only the unique are going to survive.”

Watson’s projects crisscross the United States: she has worked to link a chain of communities comprising Abraham Lincoln’s central Illinois stomping grounds; helped establish a scenic byway tracing the shoreline through the Outer Banks; and cultivated the 18th century rural feel of tiny Oley Township outside Reading, Pa. Like a shadow National Park System, such preservation efforts can encompass whole geographic areas, as with the Niagara Falls National Heritage Area in New York. The unique zone, pivotal to early American conflicts and later American industry, includes the Falls themselves, as well as three historic landmarks.

Such “living national landscapes” help visitors from around the world access these places and learn their stories, Watson says.

Amidst a burgeoning sustainability movement and a housing crisis that gutted exurban cul-de-sacs nationwide, Americans are becoming more aware of, and attuned to, their environments. Watson’s work taps into this slow-living sensibility, which places charm, quirk and character above smokestacks, sprawl and strip malls. Her work, she explains, goes beyond individual buildings.

Watson helped Oley stop sprawl in its tracks after a blast from a limestone quarry cracked and permanently drained one of the most vital natural springs in the region. After that agricultural and environmental catastrophe, residents “realized that they were facing things outside their control,” Watson says. Then working for the National Trust for Historic Preservation, Watson helped community farmers keep their land untouched, in part through state incentives. As a result, much of Oley is protected land, making it the largest historic landscape in the National Historic Register. An official designation Watson says, gave Oley citizens “a confidence that they were the stewards of something that was really, really important.”

Now, red-roofed stone buildings from nearly three centuries ago punctuate green meadows. In surrounding townships that lack such protections, subdivisions stuffed with single-family homes blanket rich Oley Valley farmland. The landscape truly changes, Watson says, when you cross over the Oley Township line.

Watson undertakes her collaborations with communities with an eye toward economics, revealing historical narrative and working with people to create truly wonderful places to live. A thoughtful approach to community preservation can inject a renewed sense of pride into a place; perhaps more critically, new industries such as heritage tourism can also attract much-needed dollars.

“What underlies what we’re trying to do to save the countryside and plan our communities … is the economic landscape,” Watson says.

A City Reborn

In Greenville, S.C., Mayor Knox White (’76) knows the contours of that hidden economic landscape better than most. The city’s longest-serving mayor has overseen the transformation of Greenville’s downtown from a blighted, boarded-up industrial zone to a vibrant gathering spot. The four-lane Camperdown Bridge overpass sealed off a natural waterfall in the center of town for four decades. “For 40 years,” White says, “the community forgot the falls (were) even there.”

In Greenville, S.C., Mayor Knox White (’76) knows the contours of that hidden economic landscape better than most. The city’s longest-serving mayor has overseen the transformation of Greenville’s downtown from a blighted, boarded-up industrial zone to a vibrant gathering spot. The four-lane Camperdown Bridge overpass sealed off a natural waterfall in the center of town for four decades. “For 40 years,” White says, “the community forgot the falls (were) even there.”

Now, the lovely Reedy River Falls — spanned by a graceful German-engineered suspension bridge — are the crown jewel in the city’s 26-acre central park. Opened in 2004, the $13 million Falls Park boasts 18 miles of walking trails. In 1982, before walkability was trendy, Main Street was narrowed from four lanes to two. The city planted trees along the main drag, which have matured into a canopy of green. The 1925 Poinsett Hotel, shuttered for nearly two decades, is renovated and back in business. And with the park as a major draw, a new crop of about 75 restaurants, plus shops and upscale residential space, has sprouted up around it. All told, Falls Park has helped bring a $150 million jolt of private investment into the local economy.

On a Sunday afternoon in downtown Greenville, you’ll find sidewalks and trails jammed with diners, theatergoers, joggers and kids, White says. “We’ve really turned into a strolling city.”

Greenville’s singular mix of green space, retail and high-rise living has attracted business to the city and won it national accolades for livability. The city’s transformation extends to the new baseball stadium downtown, Fluor Field, a mini-Fenway Park for the Greenville Drive, a Boston Red Sox affiliate. Part of White’s secret to success is long-term vision: the downtown revitalization is part of a 30-year commitment to the area.

“It’s kind of gone from good to great just within the last 10 years,” says White, who works as an immigration lawyer.

This focus on quality of life has helped the city of more than 58,000 to weather the recession, even as other communities struggle to recover. A $100 million mixed-use office development is under way; building of new downtown apartments can’t keep pace with demand. From the window of White’s 10th-floor office in City Hall, no less than three construction cranes are visible, a reminder that Greenville isn’t done growing.

Local Roots Run Deep

Nearly 150 miles northwest, Bob Jarnagin (’76) can enjoy the fruits of his devotion to Dandridge, Tenn., from the window of his office downtown. The panorama includes the old Revolutionary Graveyard and the Shepard’s Inn, a 19th century tavern where Presidents Andrew Jackson, Andrew Johnson and James Polk each spent the night. Today, it’s being refurbished as a bed and breakfast.

Nearly 150 miles northwest, Bob Jarnagin (’76) can enjoy the fruits of his devotion to Dandridge, Tenn., from the window of his office downtown. The panorama includes the old Revolutionary Graveyard and the Shepard’s Inn, a 19th century tavern where Presidents Andrew Jackson, Andrew Johnson and James Polk each spent the night. Today, it’s being refurbished as a bed and breakfast.

Jarnagin has powerful ties to Dandridge, seven generations back. His ancestors were among the first settlers in Jefferson County and operated the first gristmill. Stories from Jarnagin’s father of Dandridge days gone by sparked his interest in local history.

“I love Dandridge, this community,” Jarnagin says. “I feel like it’s in my genes.”

Outside Knoxville at the foot of the Great Smoky Mountains, one of the oldest towns in Tennessee was designated a National Historic District in 1973. Jarnagin, mentored by former Jefferson County Historian George Bauman, has thrown himself into bringing Dandridge’s colorful past alive in the present.

He chairs the Dandridge Historic Planning Commission and heads the design committee of the Dandridge Community Trust. Several years ago, he was named Jefferson County Historian. After combing through centuries-old property deeds during a stint on the city Board of Mayor and Alderman, he created and leads walking tours through Dandridge’s quaint downtown Historic District. That passion has paid off: In 2011, the town was chosen as one of the National Trust for Historic Preservation’s Dozen Distinctive Destinations.

Jarnagin lights up telling tales of how Dandridge, on the banks of the French Broad River, was almost swallowed in 1943. An earthen dike holds back Douglas Lake, created by the Tennessee Valley Authority to generate hydroelectric power for nearby Alcoa to produce aluminum for World War II aircraft, as well as Oak Ridge, where scientists were secretly working on the atomic bomb.

Even further back in time, Dandridge was a major stop for settlers heading west down the Shenandoah Valley along an ancient Native American trail, later becoming a stagecoach stop.

“The story of Dandridge is as much about preservation as it is about revitalization,” Jarnagin says. “The buildings had been neglected, but they were still there. The original windows, the original doors, the original hardware and architecture were just waiting for someone to restore it. The bones of Dandridge’s taverns, mansion and drug store were intact, vacant and forgotten. White paint covered the original brick façade of the 1845 Greek Revival courthouse, and the original wood shake roof had long since disappeared. In the mid-1990s Jarnagin led a group of investors in buying the foreclosed 1820s Vance Building at auction, and a revitalization movement was born.

Today, the three-story Vance building is the “cornerstone of Dandridge business,” Jarnagin says, housing a café, office, apartments and antiques shop.

With historic buildings up and running, Jarnagin and local leaders are focused on beautifying Dandridge and making it more visitor-friendly. That means resurfacing sidewalks, installing matching trash and recycling bins, upgrading benches, adding planters and parking and constructing an information kiosk for tourists. Jarnagin, who runs his own insurance firm and raised his two teenagers in the house where he grew up, is eager to usher in Dandridge’s next generation.

“I’ve never found anywhere I like any better than right here.”

The Prettiest Courthouse in the Country

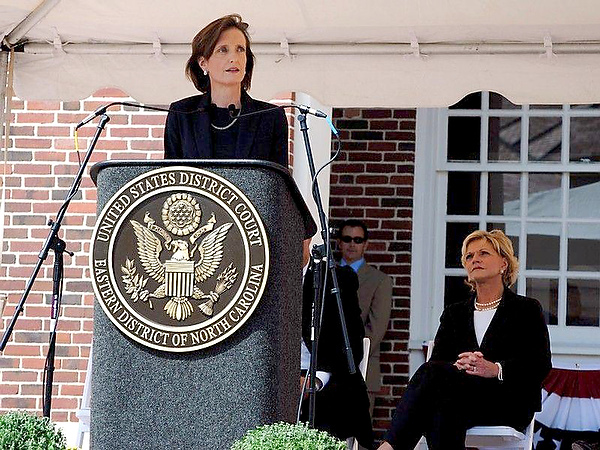

These preservation efforts, large and small, illustrate Watson’s notion of placemaking: a unique process able to encompass regions, cities and a downtown core, as with Bob Jarnagin’s beloved Dandridge. For Federal Judge Louise Wood Flanagan (’84), placemaking focused on a single, significant building. Flanagan was appointed by former President George W. Bush in 2003 as a U.S. District Judge for the Eastern District of North Carolina in New Bern, N.C. There, she led the complex, seven-year renovation of the federal courthouse. Her tireless efforts, in many cases smack dab in the middle of her workspace, restored the community’s showpiece 1935 Georgian Revival courthouse to its former glory.

These preservation efforts, large and small, illustrate Watson’s notion of placemaking: a unique process able to encompass regions, cities and a downtown core, as with Bob Jarnagin’s beloved Dandridge. For Federal Judge Louise Wood Flanagan (’84), placemaking focused on a single, significant building. Flanagan was appointed by former President George W. Bush in 2003 as a U.S. District Judge for the Eastern District of North Carolina in New Bern, N.C. There, she led the complex, seven-year renovation of the federal courthouse. Her tireless efforts, in many cases smack dab in the middle of her workspace, restored the community’s showpiece 1935 Georgian Revival courthouse to its former glory.

When Flanagan arrived in New Bern in 2003, the courthouse, a former post office and customs house listed on the National Register of Historic Places, had seen better days. The aging building didn’t meet the modern standards demanded by the Eastern District of North Carolina, with one of the largest caseloads in the nation. Plaster was fixed; the jury room was moved to make it more accessible; heating and air systems were upgraded; wiring was repaired; emergency exits and secure elevators were added; asbestos was removed; and a new holding cell and sally port for prisoners were built, among a multitude of other improvements. Some of the most dramatic changes occurred in the courtroom itself, where murals were restored, original mahogany fixtures and brass grillwork were rehabilitated and massive bronze chandeliers repaired.

To get the $14 million project in motion, Flanagan navigated a thicket of federal officials and agencies, transferred the title of the courthouse to the General Services Administration (GSA) and received congressional approvals and appropriations. Hurdles were both bureaucratic and physical. Flanagan explains: “An immediate goal for the 20 or so individuals who worked daily at the facility was simply to survive the onslaught of construction while getting their many jobs done. Working on site was challenging, like living through any substantial home renovation.”

At times, Flanagan and her staff had to lug files and computer equipment to area courthouses for hearings and trials; employees waded through water to reach their offices while contractors refinished marble floors, or dodged tools, debris and scaffolding. During demolition, sheetrock dust covered everything. A crane removed pews from the courtroom through a second-story window and lifted workers (and “at least one daring court employee,” Flanagan says) to the courthouse cupola to replace missing urns. And when the project was just days away from completion, Hurricane Irene wrought damage to the basement and third floor.

The impact on the community of the new courthouse, which opened to coincide with New Bern’s 300th anniversary celebration, was immediate. One older woman recounted to Flanagan how she scaled a ladder to watch for Nazi planes from the building’s cupola. The former postmaster who served in the building during the Eisenhower Administration shared how much the building meant to him, and he explained how the prominent clock on site that was removed by the Postal Service should be returned to its former place. (It was.)

“Frankly, GSA was stunned that a courthouse could be so well loved!” Flanagan said. “In so many ways, efforts to make the United States Courthouse at New Bern ready for the future have renewed its ties with the past.”

Writing the American Story

Preservationist Elizabeth Watson understands such ties better than most, and highlights the importance of narrative and story, to history and the “struggle to understand the meaning of what happened in a community.” She has authored books on saving special places, and she empowers communities to write their own histories.

“People would like to experience more of the American landscape, more of the American story.”

Intentional preservation efforts work, Watson says, “but it takes imagination and determination and a certain amount of going against the conventional wisdom.” Watson credits her Wake Forest history professors such as emeriti James Barefield and J. Edwin Hendricks with helping set her on the path of placemaking.

“Sterling Boyd’s architectural history course — that’s where the earth shook in terms of why I’m doing what I’m doing now,” Watson says. “I can picture slides that he showed us. I was hooked.”

The former art department chairman taught her “the ability to see all that and to understand how easily you can see history in the landscape.”

Mayor Knox White tells a similar tale from his days as a history major, fondly recalling Barefield and time spent at Casa Artom in Venice, and naming history professor emeritus Howell Smith (P ’84, ’91) as a mentor.

At Wake Forest, Watson, White, Jarnagin and Flanagan learned to love — and live — history; now, these creative leaders are dotting the American countryside with communities that have their futures anchored firmly in their pasts.

Former newspaper journalist Susannah Rosenblatt (’03) is senior communications officer for Nothing But Nets at the United Nations Foundation in Washington, D.C. She lives in Arlington, Va.