Last April I was fortunate enough to make a long- overdue visit to Wake Forest. Mary DeShazer, professor of English and Women’s and Gender Studies, delivered the prestigious Hubert McNeill Poteat Lecture, and afterward I attended a special gathering to honor her. Catching up with many of my women’s studies professors I had vivid memories of how supported and acknowledged I felt by this close-knit community. I remembered how passionate I had been about confronting injustice as a student and how I found my voice to speak out for what I believe in. I could see a clear connection between the person I was becoming then and the person I am today.

As an incoming freshman at Wake I struggled to find my place. Although it was clearly divine intervention that paired me with the best roommate I could have asked for, I felt overwhelmed by a feeling that I was on the outside looking in. I was seriously considering transferring when an extraordinary opportunity arose that year. I was invited to be the student representative on the Women’s Studies Steering Committee, giving me the unique experience of working with a small group of professors. Our team shared similar values and ideals, as well as a deep commitment to social justice. Over the years these professors became mentors and good friends. Their constant support and encouragement throughout my years at Wake was pivotal, affecting both my personal and academic development. This sense of community was essential in helping me to feel rooted as I began to find my way.

As an incoming freshman at Wake I struggled to find my place. Although it was clearly divine intervention that paired me with the best roommate I could have asked for, I felt overwhelmed by a feeling that I was on the outside looking in. I was seriously considering transferring when an extraordinary opportunity arose that year. I was invited to be the student representative on the Women’s Studies Steering Committee, giving me the unique experience of working with a small group of professors. Our team shared similar values and ideals, as well as a deep commitment to social justice. Over the years these professors became mentors and good friends. Their constant support and encouragement throughout my years at Wake was pivotal, affecting both my personal and academic development. This sense of community was essential in helping me to feel rooted as I began to find my way.

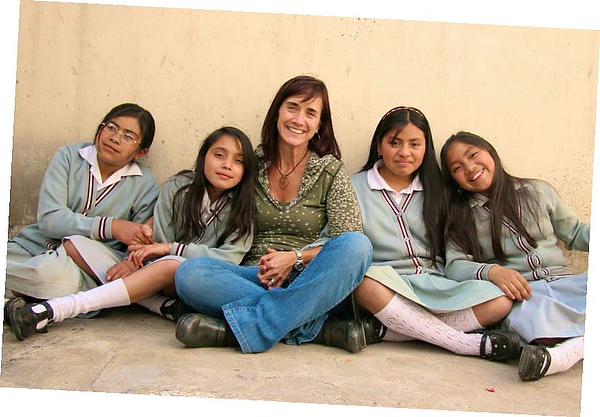

It’s 1 p.m., and I am standing on a street corner under the hot sun, in Quetzaltenango, Guatemala. Our youngest students are making the 15-minute walk from their elementary school to the Education and Hope after-school program, and one of the highlights of my day is waiting outside the door of our building to welcome them. It is pure joy to watch those at the front of the line craning their necks to see if I am at my post, smiles breaking out when they realize I am there to greet them. Each child waits patiently for a kiss and a hug before heading inside for lunch. You can feel the room begin to buzz with contentment, along with a collective sigh that signals “happy to be home.”

I first arrived in Guatemala in 1994 to study Spanish in an immersion program and never would have imagined then I would still be living there two decades later. The immersion program featured community service projects as an integral part of learning. The school regularly dispatched its students to rural homes to make cement latrines for families without indoor plumbing and brick stoves to replace cooking over open fire. We witnessed the jarring level of extreme poverty — dirt floors and barefoot children, a solitary bulb hanging as the only source of light. But even more shocking was our realization that many children didn’t attend school. Families that had trouble putting food on the table couldn’t afford registration fees or school supplies. It was inconceivable to me that a public school system existed out of most children’s reach.

Eager to continue my volunteer work but without resources for room and board, I raised money through friends and family back in Connecticut. As my relationships with families in the rural communities grew, I began to share these funds with people I knew who needed help. One by one, I enabled a few children to attend school. In 1997, with a miraculously unexpected donation of $20,000, I founded Education and Hope as a nonprofit.

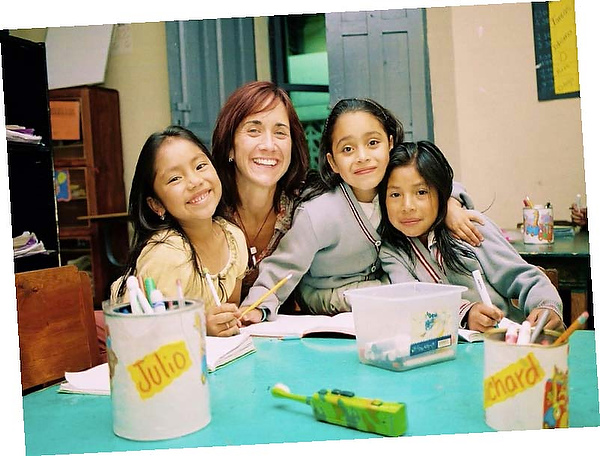

That first year I offered more than a dozen children scholarships to attend a modestly priced, privately run school. Each child received a pair of shoes, a backpack filled with school supplies, a school uniform and bus fare to travel back and forth into the city. I quickly learned that while these gifts were important, other serious issues worked against academic success. Hungry children struggled to pay attention in class, as did children with illnesses families couldn’t afford to treat. Without sufficient schooling of their own, parents could not help with homework. In response, I invited the kids to come to my home each day for a hearty lunch and a homework session. This nourishment of bodies grew and deepened into a nourishment of souls, and the true nature of the support we provide started to take shape. What I began to see was that, more than anything else, love and a sense of belonging were at the root of what helped these young children thrive.

Today, the after-school program provides academic reinforcement to 100 students each day; meals and medical care; and showers and clothing to promote cleanliness and a sense of dignity. Our scholarship program supports over 200 children of all ages, through university. Because of the cost, only a tiny percentage of Guatemalans go to college, so I am extremely proud that 46 of our scholarship recipients are university students.

I know from personal experience how financial strain can interfere with academic success. While I was very fortunate to have scholarships, loans and work-study to help finance my education at Wake Forest, I still often came up short. I remember starting one semester in a panic, unable to buy all of my textbooks. Somehow I found myself in the office of then-University Chaplain Ed Christman (’50, JD ’53), and he provided what I needed from a special emergency fund, no strings attached. I can instantly recall the astonished relief and deep gratitude that washed over me as I walked to the bookstore that day.

A heartfelt conversation with Stephen Boyd, one of my religion professors, guided me in my decision to take a semester off to work before starting my senior year. When I returned I had saved enough to focus entirely on my studies without distraction, earning the best grades of my four years.

Reflecting on my years as a student, it is gratifying to see that the same themes of community and belonging that made such a profound difference in my experience at Wake are also at the root of what makes Education and Hope so unique. While our program aims to provide these children with the education they need to help break the cycle of poverty, the real work that we do is to remind each one of their inherent worth, that each might know beyond a doubt that they are loved.

I am both proud and hopeful to see Wake Forest continually challenging and expanding its commitment to the ideals of Pro Humanitate. Sharing our gifts by serving others helps us to recognize how deeply connected we are, that all of our lives are uplifted by acts of kindness that ease the burden of another. Jesuit priest Gregory Boyle often speaks of helping people to “see the truth of who they are, that they are exactly what God had in mind when God made them.” This is the essence of what Pro Humanitate means in my life. It is my deepest privilege to work in this way in Guatemala, encouraging others to feel the fullness of their humanity. In turn, I am blessed as they return me to the fullness of my own.

Julie Coyne (’89) majored in religion with a minor in women’s

studies. She is the founder and director of Education and Hope (educationandhope.org), splitting her time between Guatemala

and Connecticut.