How we eat determines, to a considerable extent, how the world is used.

— Wendell Berry

My years at Wake Forest nurtured a boundless curiosity, a love of learning, and a sense of duty toward the future. A couple of major influences stand out. Under the tutelage of literature professor Ed Wilson (’43), “Beauty is truth; truth, beauty” impressed me as not just a pretty turn of phrase but a profound metaphor for our relationship with the natural world. Religion professor Mac Bryan (’41, MA ’44, P ’71, ’72, ’75, ’82) helped me appreciate that, when it comes to the biggest questions of morality, the person I most need not to let off the hook is me.

I abandoned the goal of an academic career after a second year of graduate school and pursued a “gypsy” lifestyle for a while, including a couple of years in rural Norway with my first wife Evelyn Knight (also Class of 1966) and three years at a Zen retreat, where I settled a restless mind, served as head gardener and met my second wife, Ellen.

I abandoned the goal of an academic career after a second year of graduate school and pursued a “gypsy” lifestyle for a while, including a couple of years in rural Norway with my first wife Evelyn Knight (also Class of 1966) and three years at a Zen retreat, where I settled a restless mind, served as head gardener and met my second wife, Ellen.

Ellen and I share a passion for good food but have despaired of what’s available from the vertically integrated, ever more anonymous food system our research indicates has everything to do with rising levels of obesity, diabetes, cancer — even debilitating diseases among children once thought the exclusive bane of the very old.

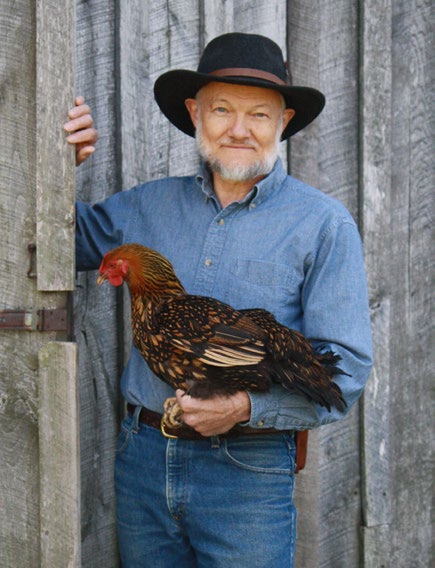

A yearning for better food — and a more intimate relation with our food — brought us eventually to our home of 30 years on three good acres in northern Virginia, where we have gardened, kept dairy goats and chickens, cultivated mushrooms and tended a small orchard. Food we don’t produce ourselves we buy mostly from farmers nearby. The rewards go far beyond more wholesome food — to a more joyful intimacy with the natural world and the satisfaction of producing for ourselves rather than continuing as passive consumers.

Though I majored in religion at Wake Forest, I moved over time to a spiritual perspective I cannot label. But I have retained from my religious studies an abiding sense of responsibility for the choices I make, both for their effects on others and the way they help shape the future. With a reflex honed at Wake Forest to consider every issue in the widest context, I explored the source of industrial food in an agricultural system that creates risks not just for me, but also for the entire ecology. I have been influenced especially by Wendell Berry’s indictment of the mechanized, chemicalized, bigger-is-better assault on the natural world that American agriculture has become, and his vision for the sustainable agriculture we must put in its place.

Most of my courses required term papers, and the high standards demanded inspired me toward writing that is clear, logical and pleasing to read. Inspired as well by the Wake Forest culture of “passing it on,” I determined to share my vision for a regenerative agriculture through writing, and in seminars from Maine to Texas. I emphasize to my reader or audience that industrial agriculture contributes to our most pressing crises: climate change, toxic environmental pollution, fresh water shortages, topsoil depletion and loss of species diversity on a scale equal to that following the impact of a seven-mile-diameter asteroid — the one that wiped out the dinosaurs. The implications for life on planet Earth are staggering. But I argue that profound changes in how we practice agriculture could bring healing changes in “how the world is used.”

While those reading or hearing my thoughts who are not farmers may despair of making a difference, I point out that there is one thing each of us can do: change the way we eat. Most of us have the opportunity if we choose to grow something for our tables, on however small a scale. And we can see our food dollar as first and foremost a vote — for more of the same. Spent for anonymous, hyper-processed food, it supports an agriculture that is exacerbating our most critical problems to bring us more. Paid face-to-face to conscientious small farmers nearby, it supports care and nurture of soil, air and water, revitalization of rural communities and transformation of food from commodity to sacred gift.

Harvey Ussery (’66) of Hume, Va., has written for Backyard Poultry, Countryside & Small Stock Journal, and Mother Earth News and is the author of “The Small-Scale Poultry Flock: An All-Natural Approach to Raising Chickens and Other Fowl for Home and Market Growers.” His website is themodernhomestead.us