Angela Mazaris, founding director of the Wake Forest LGBTQ Center, accomplished the two main goals for the center’s first-ever conference last weekend, but a surprise outcome amazed her.

The center supports and educates the University community on issues around identity and sexual orientation for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and questioning students, faculty, staff and alumni.

The Rising Voices conference, which brought 160 registrants to campus for sessions Friday and Saturday, easily met the center’s goal of showcasing the talents of LGBTQ alumni. The alumni who talked about their work had bios that read like a Who’s Who of successful work, arts and advocacy.

Courtney Cuff ('94), president and CEO of the Gill Foundation, and J. Robby Gregg Jr. ('83), director of diversity of AOL Time Warner, participate in a panel discussion.

The second goal — connecting LGBTQ students and alumni — happened easily, too. Students expressed huge excitement about interacting with these alumni who can mentor them in their career and life paths, Mazaris said.

But what Mazaris didn’t anticipate was how much healing happened for some alumni whose experiences at Wake Forest were formative but often painful because they lived in the closet or suffered hardship when they came out.

“This was not a happy place for some of them,” she said. But what many found during the weekend was a healing experience with a cause for optimism.

Toni Newman ('85), author of "I Rise — The Transformation of Toni Newman" and development manager for Maitri Compassionate Care in San Francisco

Toni Newman (’85), author of “I Rise — The Transformation of Toni Newman,” which has been adapted for a feature film, said she left Wake Forest feeling unwanted, unloved and disconnected as one of only a few African-American students. She is development manager for Maitri Compassionate Care in San Francisco, a hospice and residential care center for people living with AIDS; and she is a blogger and a transgender advocate.

“I came back with much fear and trepidation, and after this weekend I left with a good feeling in my gut,” she said. The weekend healed some personal wounds. “I felt the connection. You are an alumna. You are welcome. You are loved. … I felt very included in 2015, where in 1985 I felt un-included.”

Friday’s “teach-in” sessions focused on investigative journalism and advocacy work, identity in the arts community, civil rights issues beyond marriage equality, African-American transgender struggles and reconciling religious and LGBTQ communities.

Saturday’s panels covered how the LGBTQ community shares its stories, current students’ experiences and the history of LGBTQ people at Wake Forest. Keynote speaker Stephen T. Russell (’88), a developmental psychologist, shared research on how campuses and communities can become more inclusive with policies as safety nets and strong leaders as advocates.

During a panel discussion on alumni professional journeys, Courtney Cuff (’94) described her progression from golfer to environmental lobbyist to LGBTQ advocate. A native of Georgia, Cuff joined the Gill Foundation in Denver, Colorado, as president and CEO in October 2013 after 20 years in the nonprofit sector. The foundation advocates for LGBT Americans and a more prosperous Colorado. Cuff lives in Denver with her wife and son.

Cuff told a story echoed by many other alumni who described coming to Wake Forest without publicly — sometimes even personally — acknowledging their sexual identity. She was one of many speakers who expressed how far the University has come in improving the environment for LGBTQ people.

“Wake has changed a tremendous amount since I was last here,” Cuff said. “I was a scholarship athlete on the golf team. My first girlfriend was a teammate of mine. We were deeply closeted because there was no one to turn to. There weren’t any places to go to learn or connect with others.”

Working in a place where everyone is comfortable with LGBT co-workers has hugely improved career life, said Cuff and several other alumni.

Kelly Smith ('86), senior vice president and chief financial officer of Replacements, Ltd., in Greensboro, North Carolina

Kelly Smith (’86) is the senior vice president and chief financial officer of Greensboro-based Replacements, Ltd., a retailer that boasts having the world’s largest selection of silver, china, glassware and collectibles. In 2009 he was named the Triad Business Journal’s large-company CFO of the Year. He lives in Jamestown, North Carolina, with his partner of nearly 28 years and their two teenage sons.

At Wake Forest, he lived a secret life. He came out when he met his husband but kept quiet in his job at a Greensboro accounting firm. “I lived for 10 years in a very conflicted place,” Smith said.

At Replacements, one of the largest gay-owned companies in the country, he began living his life completely out, and he values the company’s agenda of promoting diversity.

“There’s something to be said for personal authenticity,” Smith said. “We also have corporate authenticity. … We are helping other organizations realize they need to change their workplace policies, and many have, based on what we’ve done.”

William Hawk ('93), information sciences expert

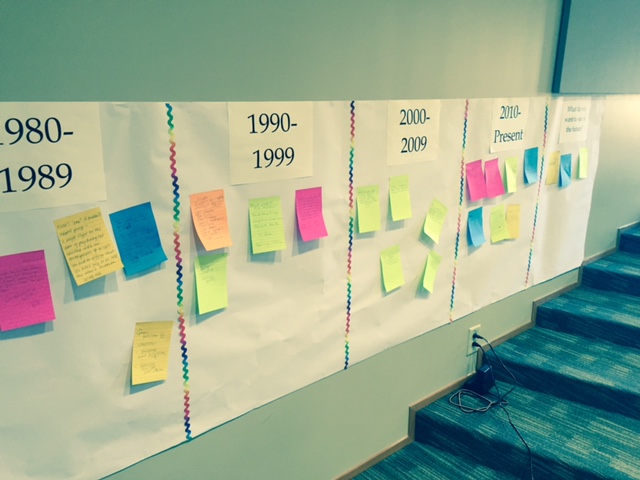

Collecting individual oral histories from alumni was an important part of the conference, and one panel was devoted entirely to the history of the University’s LGBTQ community.

The panelists told painful stories mixed with bright moments of support. William B. Hawk (’93) has more than 20 years of experience in information work supporting public charter education systems and related organizations. He remembers an epiphany as he sat in a dark, dingy bathroom in Tribble Hall and read graffiti slurring three gay men by name. He knew them, and “in my mind, my name was emblazoned there.”

He turned into “an army of one, putting up posters” in 1991 for the newly created association whose name later evolved into the Gay-Straight Student Alliance. There was an outpouring of support, and the University funded the group, despite objections.

“My parents disowned me,” Hawk said. “I got my scholarship enlarged so I wasn’t struggling so much to finish my final two years.”

David Styers ('92), manager of program and business development at the Presidio Institute in San Francisco

David Styers (’92) said he came to Wake Forest from a small town in North Carolina as a “homophobic homosexual.” Today, Styers is the manager of program and business development at the Presidio Institute, a Presidio Trust initiative in San Francisco.

“I was not outing anyone, certainly not myself,” Styers said of his arrival at Wake. In his senior year, he realized “I needed to do something to prepare myself to graduate as a gay man,” Styers said. He saw posters for LGBTQ support.

“I walked into the room, almost hyperventilating, and I knew almost everybody there. … I thought, ‘Maybe there is a world out there,’ ” Styers said.

He lost his senior roommate after telling him he was gay. “We had known each other for four years, been through a lot, and within two weeks he had moved out,” Styers said. The roommate continued using the dorm room to socialize. But an assistant director in housing who was gay told Styers he could change the locks, and they did. The roommate took revenge by outing Styers on campus.

“(My roommate) thought he was the injured person, that his life and reputation had been ruined,” Styers said. “(S)omeone asked me, ‘Why didn’t you transfer?’ But I didn’t need to. Wake Forest was looking out for me.”

Styers told his family on New Year’s Day 1992, and they wanted to take him to counseling “to fix me.” His support on campus gave him the strength to resist. “When I graduated, I felt I had the backbone to leave North Carolina, which I never thought I would do, and go to Washington, D.C. I’ll always be grateful.”

Perry Patterson retired from Wake Forest as an economics professor and lecturer in Russian in 2013 and as associate dean for academic advising in 2012.

Perry Patterson, who was the first faculty adviser to the GSSA, came with his husband, Joel Leander (JD ’90), to Wake Forest in 1986. Patterson said upper administration was “frightened to death of these issues. They didn’t know how to handle it.” As early as 1993, the faculty passed a resolution against gay discrimination. As one of the first openly gay faculty members, Patterson said the environment was generally “don’t ask, don’t tell.” Patterson retired as an economics professor and lecturer in Russian in 2013 and as associate dean for academic advising in 2012.

Susan E. Parker (MDiv '02), coordinator of Relatives as Parents Program through Forsyth County Department of Social Services

Susan E. Parker (MDiv ’02) told of the firestorm involving trustees and the University over efforts by Wake Forest Baptist Church to hold a same-sex wedding ceremony in Wait Chapel.

Parker said Wake Forest Baptist Church had its first openly gay member in 1988, and as the ’90s progressed, she wondered why she and her partner couldn’t have a wedding ceremony in Wait Chapel. The church has always been allowed rent-free space but is not affiliated directly with the University. She said the church debated the issue internally from 1997 until late 1998. In the next two years, there was community debate, decision-making — and Parker says foot-dragging — by University administrators and trustees, miscommunications, petitions, news coverage, editorials and protests.

On Sept. 9, 2000, the ceremony was held. Parker currently coordinates the Relatives as Parents Program through Forsyth County’s Department of Social Services. She lives with her wife, their daughter and two grandchildren.

“At that point, the only state that had talked about gay marriage was Hawaii,” Parker said. “I never thought I would see this (current legalization of gay marriage) in my lifetime.”

Tré Easton ('13), former Student Government president, now Special Assistant to the Assistant Secretary for Congressional and Intergovernmental Affairs at the U.S. Department of Energy<br />

As the youngest alumnus on the panel, Tré Easton (’13), the first openly gay president of Wake Forest Student Government, said, “I have never not felt like I was at home at Wake Forest. There was this immediate palpable energy that I felt, a oneness with this place.”

The only time his sexual orientation came up was when a campaign team member asked whether it might be an issue with fraternities. But it never happened.

“Wake Forest students are amazing,” he said. “I encountered people who really want to do things on campus. People wondered if I had some radical agenda, but that’s not who I am. I felt that people were wanting to engage but didn’t know the questions to ask.”

Wake Forest “taught me to understand another person’s truth. I may not support it, but I have to understand it,” he said.

A board in the Z. Smith Reynolds Library Auditorium for adding history recollections at the LGBTQ conference

Mazaris said the center chose to have the conference now because she was hearing from students, faculty and staff that they want more education and understanding.

“Why now? At four years, we’re built. We’re here. We’ve got our core programs in place. It felt like we were in a place where we can look at inviting new connections between alumni and faculty and staff and leverage the expertise of our Wake Forest community.”

Mazaris is optimistic about what comes next. When she arrived on campus with the mandate to create the LGBTQ Center, some questioned why such a center was needed. Why not a center for straight people, the argument goes.

The answer is that we live in a changing world, she said. “We cannot prepare our students to succeed in our world if we don’t prepare them to work in a diverse world,” she said. “Corporations don’t want to hire someone who doesn’t have some baseline ability to work with people who are different from themselves.”

The center’s work, she said, has benefits for the entire University. “If we have a learning environment where students are not able to bring their whole selves, then we’re creating a community where people aren’t fully engaged,” she said. “The LGBTQ Center is here to create a climate where all our students feel nurtured and appreciated for who they are, not who they are pretending to be.”

Carol L. Hanner is former managing editor of the Winston-Salem Journal and a writer and book editor.