This story could begin with a KEY, a SEASHELL, a ROCK or a BOOK, but it seems only fitting to begin with dearly departed Frederick the hamster. May he rest in peace in that orange see-through-plastic purse hanging on the wall inside the home of Wake Foresters Anne and Paul Gulley.

Frederick once scampered and entertained the three Gulley children in the family’s 1889 house on the hill in Elkin, North Carolina, a former textile town 40 miles west of Winston-Salem. He lived out his life, one would hope, happily. When Frederick died in 1994, the Gulleys thought he could, with the help of a taxidermist, in the way of prized animals in the rural South, stick around forever. As Anne tells it, she first approached the most famous taxidermist in the area, but he scoffed at such a puny task as stuffing a hamster. A woman taxidermist proved game, saying she would get right on it and “put him in the pickle.” No one in the Gulley family knew much about taxidermy, but that sounded OK to them.

Eventually Anne and the children arrived at the shop to fetch Frederick. “The children’s eyes were big,” Anne says, not in a good way. In death Frederick was larger than life and a tad horrifying. The taxidermist explained that she didn’t have a hamster “form,” so she had to make do with a squirrel form, over which Frederick was stretched. And so Frederick went back home to West Main Street not quite the fellow he used to be but tolerable if one appreciates a squirrel-hamster mix.

He now resides visible in the orange purse, which has a place — alongside the key, the rock, the shell and the book — in the Gulleys’ “wunderkammer,” also known as a cabinet of curiosity, formerly the library. Frederick and the (nameless) caiman on the ceiling have top billing when the Gulleys invite neighbors and strangers to their home on international Obscura Day. Last year it was May 30. Perhaps you missed it.

Anne ('77) and Paul ('74, MD '78) Gulley

Obscura Day began, as so many hipster passions do, in Brooklyn. Dylan Thuras and Joshua Foer liked scientific discovery, adventure and weird things off the beaten path. They created the Atlas Obscura website to serve as a roster of unusual places and things, from “the world’s most controversial inflatable yellow duck” to “atomic artifacts at the National Atomic Testing Museum.” In 2010 they launched a global day of celebration at museums, homes, cemeteries, underground tunnels — last year 150 events in 39 states and 25 countries — “all designed to celebrate the world’s most curious and awe-inspiring places.” The Gulleys’ wunderkammer was the only site listed in North Carolina.

Anne (’77), a fine-arts painter and all-around community booster, remembers writing Thuras to ask whether she and Paul (’74, MD ’78) had a wunderkammer that might qualify for hosting Obscura Day and its celebrants. “He wrote back immediately and said, ‘Madam, you most certainly do.’ ” To her amazement, she says, for about a month afterward the website touted the upcoming Obscura Day with “New York, Tokyo, London, Paris, Elkin, N.C.”

Though he has never seen it, Thuras was enthusiastic when interviewed about the Gulleys’ cabinet of curiosity, noting in an email that the Gulleys had hosted Obscura Day four times, and “(Y)es, why not! Elkin has as much in the way of wonder as anywhere! Paris can be boring and Elkin can be amazing. (I)t’s all in your perspective. It’s all in how you look.” As for the Gulleys, he said, “Give them my regards and let them know I’m coming to the museum soon! (I [sic] let them know first, ha!)”

Anne and Paul had a streak of quirky trailblazing in their bones even back in their Wake Forest days. Paul, from a long line of Wake Foresters, moved to campus from the house of his parents — Dr. Marcus Gulley (’47, MD ’51) and Sally Hudson Gulley (’48) — less than five miles away. He arrived itching for adventure. Anne came from Toledo, urged by her Demon Deacon dad, William Franklin Connelly (’49), to follow in his footsteps if she wanted him to pay for college. They met in the Outing Club, which, as Paul, likes to joke, “had a different meaning back then.” He was one of the founders of the outdoor recreational group that traveled all over the state on camping and hiking trips. She was a freshman and he was a senior when they met. His extremely independent group of guys in Kitchin dorm liked to sneak around and pull pranks, memorably climbing up the water tower and painting it, twice. (You might call what they painted a birdlike salute.) She and her friends, after art class, once skinny-dipped in the Reynolda House pool. Another time, she, Paul and friends launched a “Mission Impossible”-style operation and danced atop Wait Chapel before dawn.

“Hey, it was the ’70s,” Paul says.

“Hey, it was the ’70s,” Paul says.

They also shared a passion for anthropology classes. Paul traveled twice with Professor David Evans (P ’97) on summer trips to the jungles of Costa Rica and, as a medical student, once to Honduras. Anne took nearly every anthropology class required for the major but switched to art after she realized “I was about the objects” and destined for a career that did not require “shoveling dirt.” She relies on both courses of study when she conducts an annual art history program with sixth-graders in Elkin and when she works with AP English students from the local high school, lately teaching them about “Antigone.”

Anyone meeting Paul and Anne would have no question that the Gulleys are lifelong learners, passionate readers and enchanted, indeed still amused, by each other. Anne wouldn’t agree to move to Elkin — where Paul had spent eight weeks in a medical school rotation — until she had checked out the suitability of the public library. It passed her test, and she and Paul set out to make their way in a small town, today population 4,001, where their children attended school practically in the backyard and Paul was soon running into patients in all aisles of the grocery store.

“What I like to say about Elkin is the good things and the bad things are the same things,” Paul says. He uses the same description, with a big laugh, in describing the Gulleys as a couple. “The good things and the bad things are the same things. Holy cow. I don’t think of us as individuals. It’s hard to put it into words. It’s not like we’re opposites. I guess we’re two sides of the same coin.”

“What I like to say about Elkin is the good things and the bad things are the same things,” Paul says. He uses the same description, with a big laugh, in describing the Gulleys as a couple. “The good things and the bad things are the same things. Holy cow. I don’t think of us as individuals. It’s hard to put it into words. It’s not like we’re opposites. I guess we’re two sides of the same coin.”

Anne calls herself the artist and Paul, who claims an artistic blind spot, the scientist. “I think we’re both curious about the world, which leads us to pursue interests separately together,” Anne says. “When I have a science question, I ask him.” Which means, conversely, that when Paul is told by his wife that she has an art vision that needs his assistance, he laughs in his good-natured way and says, “Yes, ma’am.”

"It's hard to put it into words. It's not like we're opposites. I guess we're two sides of the same coin."

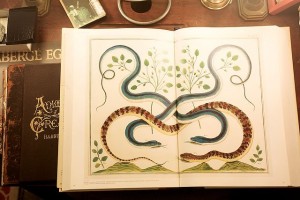

The vision came when Anne read “Mr. Wilson’s Cabinet of Wonder” by longtime magazine writer Lawrence Weschler of The New Yorker. The book describes oddball exhibits at David Wilson’s Museum of Jurassic Technology in Culver City, California, including The Stink Ant of Cameroon and a preserved horn that purportedly grew out of the head of Mary Davis of Saughall. (On this day Anne proudly shows off that she is wearing her colorful “horn” earrings from the museum, modeled after the horn of Mary Davis.)

Weschler recounts how the Jurassic’s roots are the “wonder-cabinets” that became fashionable in the 1500s and 1600s. He speaks to that history in a YouTube video filmed at the Curiosity Cabinet Symposium at Seton Hall in 2011 (with Anne in the audience): “You would find every gentleman had his wonder-cabinet filled with completely strange and odd objects,” things like beavers taken from the River Elbe, beetles, shells, ivory carvings, coral, a Madonna made of feathers. “It was all about marvel,” he said, suggesting that the reason was the discovery of America. “There’s this sudden vogue for having your heart tremble at something,” he said. Purple parrot feathers, moose antlers, sacrificial urns. America and Africa, he said, “were blowing Europe’s mind.”

Weschler recounts how the Jurassic’s roots are the “wonder-cabinets” that became fashionable in the 1500s and 1600s. He speaks to that history in a YouTube video filmed at the Curiosity Cabinet Symposium at Seton Hall in 2011 (with Anne in the audience): “You would find every gentleman had his wonder-cabinet filled with completely strange and odd objects,” things like beavers taken from the River Elbe, beetles, shells, ivory carvings, coral, a Madonna made of feathers. “It was all about marvel,” he said, suggesting that the reason was the discovery of America. “There’s this sudden vogue for having your heart tremble at something,” he said. Purple parrot feathers, moose antlers, sacrificial urns. America and Africa, he said, “were blowing Europe’s mind.”

Weschler’s book blew Anne’s mind. “I just had this moment. I’ve got one of those!” she said of the wonder-cabinets. “And it’s scattered all over my house. It’s in the drawers and on shelves. And so I just had this thought: We’ve got this room. Let’s do it.”

Weschler’s book blew Anne’s mind. “I just had this moment. I’ve got one of those!” she said of the wonder-cabinets. “And it’s scattered all over my house. It’s in the drawers and on shelves. And so I just had this thought: We’ve got this room. Let’s do it.”

She had to hurry. Her goal was to transform the library before Feb. 12, 2009, long before Obscura Day came to be, but a day worth celebrating in the Gulleys’ opinion. They would make the library a cabinet of curiosity in time to honor Abraham Lincoln and Charles Darwin, both born on the same day 200 years before. There was one problem. Every wunderkammer, aka wonder-cabinet, aka cabinet of curiosity, needs a stuffed alligator. Anne went shopping on eBay but gulped upon discovering the $1,200 price tag. She’s proud of her knitted dissected frog — it has its place in the wunderkammer — but it’s no stand-in for a de rigueur stuffed alligator. What’s a cabinet without the gator?

In the magical way that stars can line up, Anne was lamenting the gatorless situation to a friend at the Foothills Arts Council in downtown Elkin when the friend asked, “Have you seen the one in the basement here?” It was actually a caiman, a reptile native to Central and South America and in this case abandoned by Elkin’s defunct nature-science group. A caiman is in the family Alligatoridae, which made the basement dweller close enough, not to mention free. With fresh zeal Anne tracked down a former nature-science member, secured permission to leave with the dead reptile under her arm and enlisted Paul’s engineering expertise. Paul momentarily cast aside his day job of internal medicine with a specialty in endocrinology to round up cup hooks and fishing line to attach the beast to the ceiling in their wunderkammer. That was his most visible “Yes, ma’am” part of the artistic vision.

First came the birthday party for Abe and Charles attended mostly by Elkin neighbors and then, over recent years, four Obscura Days that each drew 70-80 people, including the guys at Lowe’s who mixed the room’s paint. The best thing about it, Paul says, is talking to the variety of people who showed up. “They would drive hours, and they didn’t seem disappointed at all.”

First came the birthday party for Abe and Charles attended mostly by Elkin neighbors and then, over recent years, four Obscura Days that each drew 70-80 people, including the guys at Lowe’s who mixed the room’s paint. The best thing about it, Paul says, is talking to the variety of people who showed up. “They would drive hours, and they didn’t seem disappointed at all.”

Paul has a special corner in the wunderkammer that contains his cherished books, particularly rich in accounts of the Civil War and Napoleonic naval war history. He especially likes the vulture wing on the wall above the fireplace: “Its structure is so amazing.” A dog dragged it into a friend’s house.

Don’t ask Anne her favorite item in the room. She couldn’t possibly name it. There are the seashells to consider, the ones she collected as a child on trips to Myrtle Beach. “They were so beautiful and mysterious. I contemplated them, imagining what went on inside,” she says. They formed her first collection. At age 8 or 9 she moved on to rocks as “a perfect combination of science and beauty.” She has those, including a treasured geode. If she had to pick a sentimental favorite it is the key to a hotel room in Germany. Her father brought it back from a business trip and gave it to her. “I used to wear it around my neck,” she says. That’s the thing about objects. Someone could look on the Internet for an image of such a key, “but holding that key in my hand connects me directly back to my dad, connects me to Europe. … It’s the touch. It’s the connection. It’s the smell. It’s all those things.”

The room contains butterflies, a tiny octopus in a jar, plastic insects, a stuffed otter — “We think that otter came from a bar somewhere,” says Paul — two skulls of horses that died during Hurricane Katrina, huge dried fungus specimens and ocean-battered glass from the lens of a New England lighthouse. It contains gifts from people who get excited about their finds and deliver them to the Gulleys to display. “I might need to let this sit outside for a while,” she tells some of them. Recently she has drawn a line not to accept anything “wet or smelly.”

The room contains butterflies, a tiny octopus in a jar, plastic insects, a stuffed otter — “We think that otter came from a bar somewhere,” says Paul — two skulls of horses that died during Hurricane Katrina, huge dried fungus specimens and ocean-battered glass from the lens of a New England lighthouse. It contains gifts from people who get excited about their finds and deliver them to the Gulleys to display. “I might need to let this sit outside for a while,” she tells some of them. Recently she has drawn a line not to accept anything “wet or smelly.”

What would make her happiest of all is if people would hold onto the things that spark wonder. “Everyone actually has their own cabinet of curiosity. It’s your kitchen sink window, the shelf above the kitchen sink,” she says. “You go for a walk and pick up a rock or a feather or something that delights you in some way. You bring it back, and you put it there.”

Look around, on your shelves, inside a chest of drawers, in the back of closets; and consider this. A stuffed alligator hanging like a chandelier might be in your future. The Gulleys would be delighted.