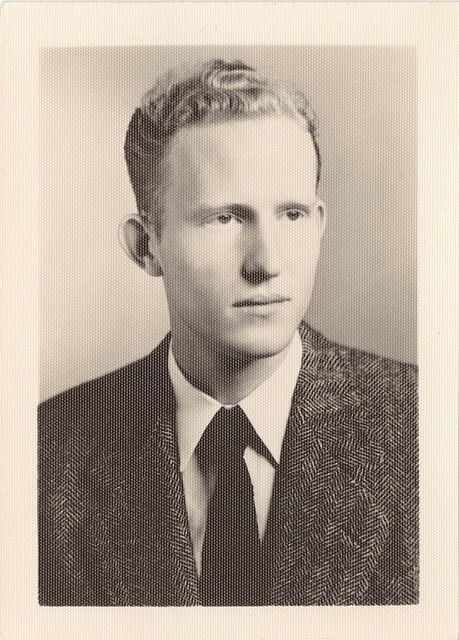

A.R. Ammons

(Photograph by Peter Marenus, Cornell University Photography,

Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections, Cornell University Library)

IN THE SUMMER of 1946, the campus of Wake Forest College in Wake Forest, North Carolina, awakened to the voices of young men returning from war and finding their way paid to go to school on the government’s G.I. Bill. Most were native sons, the first in their families to attend college, many from humble farms on the edge of going under; and they had grown up quickly, having lived close to death.

As survivors, they felt a sharpened sense of purpose, even when they did not know what it might be. They could not take anything for granted: they needed to act, to accomplish something and to better themselves. Only a few families — lawyers, doctors, landowners with vast property — were secure enough to provide entry for their sons into the ranks of the well-to-do. Most Wake Forest students had to make it on their own.

Ammons in the 1940s. <br /> (Archie R. Ammons Papers, #14-12-2665. Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections, Cornell University Library.)

One who always had understood the need to look after himself was A.R. Ammons (’49, D. Litt. ’72), who a half-century later, against all odds except his own genius, secured a place in the highest rank of American poetry. The birth of a great poet in what literary critic Helen Vendler called “the hiddenness of Whiteville, North Carolina,” was random and miraculous. Who could have picked him out, the shy boy waiting in line at the Wake Forest post office to see if there were a letter for him? He was Ammons, a tall redhaired 21-year-old from Columbus County in the eastern part of the state, where peanuts, cotton and tobacco were grown, and where there were fewer people in downtown Whiteville, the county seat, than on the small Wake Forest campus. The most successful man in his family was the sheriff of Whiteville, his father’s brother, but back in the pinewoods on a subsistence farm, Archie and his father plowed with a mule, later lost to a chattel mortgage. They were self-reliant and lived to themselves. When the farm failed, they moved into town, converting an old gas station into a house. Archie respected only what he himself earned. His English teacher at Whiteville High School encouraged his poetry writing, and he never forgot her.

Among the few things Archie carried with him to college were the journals and poems he had written over 19 months on a Navy destroyer in the South Pacific, both contraband in a different way (it was against military rule to keep the journal, and he had not told his family about his poetry writing: his father wanted him to be a boxer). As he traveled home by train across the country, he wrote in his diary, “And now to face the future — puzzling, undecided, and with little self-confidence. … what now?” He sent off letters to three colleges (he later forgot the other two), and the first to answer was Wake Forest, about three hours from Columbus County if he could catch a ride. He was accepted. “Without further deliberation,” he explained, “I made arrangements to join that fair company.”

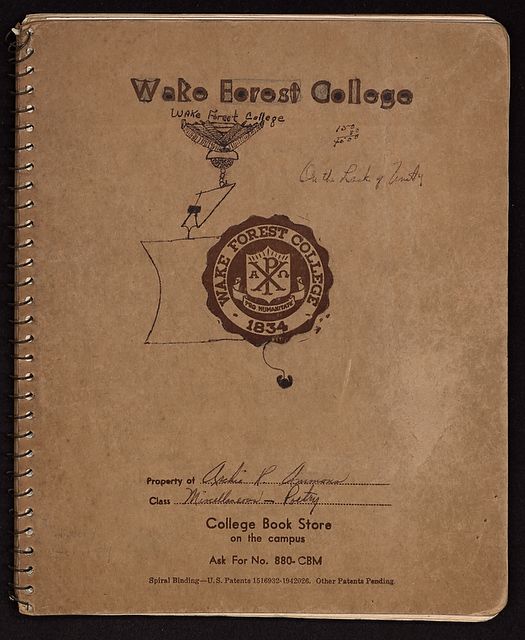

Ammons kept this notebook while a student at Wake Forest. <br /> (Notebook, A.R. Ammons Collection, J.Y. Joyner Library, East Carolina University.)

ALTHOUGH AT WAKE FOREST he was self-conscious about his clothes — he did not have a suit or an overcoat — he was proud of his books: in San Diego he had purchased a complete set of Shakespeare and the philosophy of Plato, and he ordered others from the Book-of-the-Month Club. The only books in his house were a Bible and the first 11 pages mysteriously torn from a copy of “Robinson Crusoe,” which he read over and over. He was fiercely proud of his parents and his two older sisters, but the death of a younger brother haunted him — he could neither talk nor write about it for many years, and, then, obliquely. His application to Wake Forest showed his high school transcript, for which he had been named valedictorian, and his honorable military discharge. But it did not reveal the loss of the mule or the little brother or hint that poverty, pride, anger and anxiety defined him and would fuel some of the strangest, strongest, most enduring poetry in contemporary literature, poetry which has helped many readers live their lives.

In Wake Forest Archie rented a room in a local home, visited the bursar’s office to arrange to pay his fees with his $75 monthly government check (which also had to cover his room and board), registered for classes and looked around.

In time Ammons declared a major in general science and studied hard, often afraid of failing, though he did well in his courses. He was too shy to call much attention to himself, never joined writers on Pub Row and made few friends. He had spent many of his shipboard hours reading and writing poems with a Navy buddy, and he continued to keep a journal of his daily activities. Reading, writing and keeping a journal became the disciplined ways by which he was to survive for the rest of his life. In the Navy he had been surrounded by men who lived under the same Spartan conditions and who sought out his company. Now that the war was over, he had a more difficult time finding a place where he felt as secure.

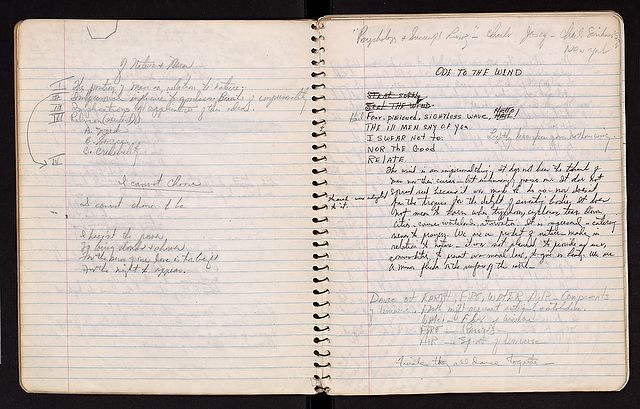

Poem and watercolor painting, 1976.<br /> (Paintings by Ammons, A.R. Ammons Collection, J.Y. Joyner Library, East Carolina University.)

On June 8, 1946, he had arrived at Wake Forest, feeling “lost — as usual.” Within weeks, however, he found what he wanted: without hesitation he began dating his Spanish teacher, Phyllis Plumbo, an exotic beauty from New Jersey, whose father was an international businessman. She accepted his invitations for campus walks, followed by listening to music and stolen kisses. At the end of the semester, Phyllis went back to work for her father in New Jersey, and she and Archie began an exchange of letters and poems, which he later remembered “deepened the life in words for me.” Over the course of his four years, including summer school, he worked toward his degree. He was graduated May 31, 1949, earning a B.S. degree in biology with honors (He was Miss Plumbo’s A student). “It’s done now and bloody,” he wrote in his diary, on his way to his first job as a school principal in coastal North Carolina. In November he and Phyllis married and went to Hatteras. The next year, encouraged by his wife, they moved to the University of California at Berkeley, where he studied with the poet Josephine Miles, but he did not stay to finish a graduate degree. He was too far from home — his father was unwell, and he felt he was needed. He took a job with Phyllis’ father in New Jersey, wrote poems and sent them out for rejections and occasional acceptances, but he felt anxious and alone. In 1955 he self-published his first book, “Ommateum.” In 1964, invited to give a reading at Cornell University, he made such an impression that the English department hired him to teach creative writing. When he retired in 1998, he was one of the best known and beloved professors on an elite faculty with an elite student body, and he won all the most prestigious national poetry prizes.

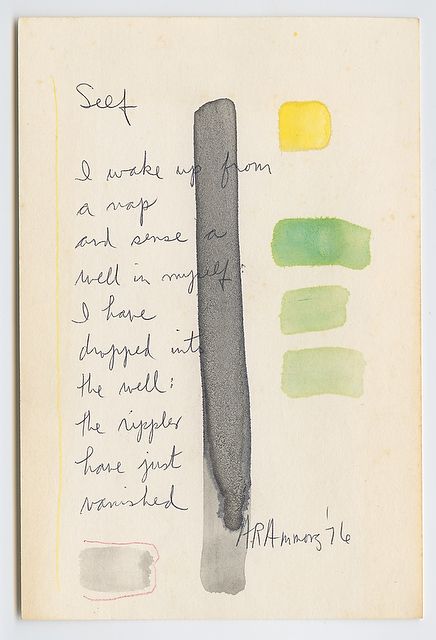

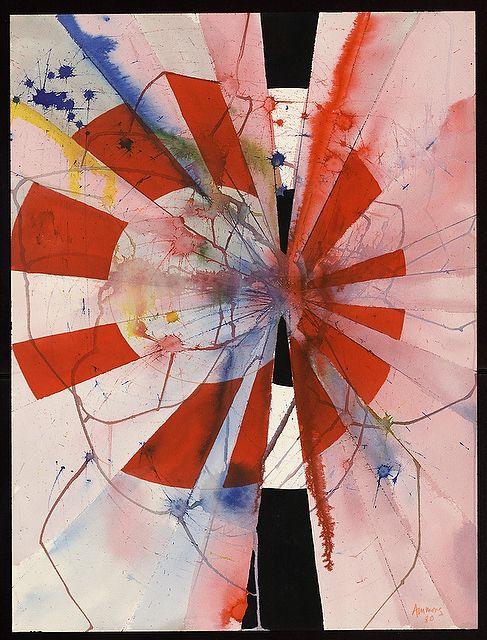

Untitled abstract watercolor, 1980.<br /> (Paintings by Ammons, A.R. Ammons Collection, J.Y. Joyner Library, East Carolina University.)

WAKE FOREST INVITED Archie back in 1972 to receive an honorary degree. He was surprised: he remembered that as a student at Wake Forest he had felt “invisible.” He had never seen the campus in Winston-Salem, and the occasion was also a chance to see his sisters, both living in North Carolina. At an English department reception at Professor Elizabeth Phillips’ house, he was overcome by shyness again and wandered off to talk with Sally, my and Ed Wilson’s 4-year-old daughter. It settled him down, and he made a lasting friendship with us and with many others. He returned later to teach various times as visiting writer, becoming the Pied Piper of poetry. During those times he and Phyllis and their young son John lived in the faculty neighborhood — once in the home of Meyressa Hughes (’62, JD ’68) and Don Schoonmaker (’60) and later at Josie and Harold Tedford’s (P ’83, ’85, ’90) during sabbaticals. Archie enjoyed reading poetry with Louise and Tom Gossett (and their cat, Napper Tandy). In subsequent years he came back for special occasions and in 2010 the library held a seminar in his honor and inaugurated the Ammons gallery, where 20 of his original watercolors are displayed. When he died Feb. 25, 2001, services were held at Davis Chapel and at Reynolda House Museum of American Art, with Helen Vendler giving the memorial lecture. The English department named its faculty lounge for Ammons, where his old upright Underwood manual typewriter is on display. The A.R. Ammons poetry contest is held annually in Columbus County. Associate Professor of English Robert M. West (’91) at Mississippi State University has edited “Complete Poems,” the forthcoming two volumes of Ammons’ poetry.

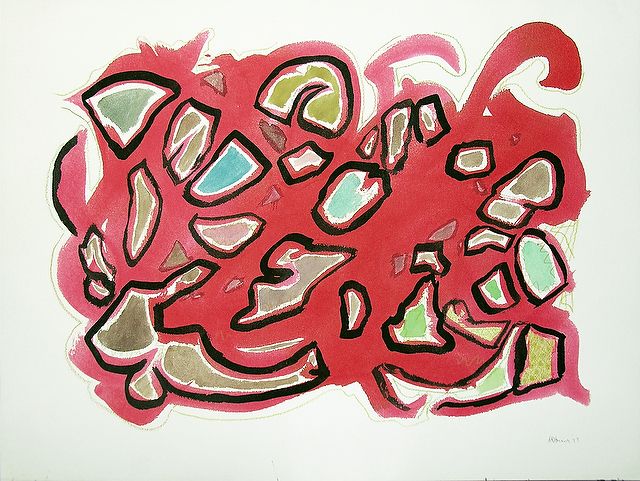

Untitled abstract watercolor, 1977.<br /> (Painting by Ammons, © Estate of A.R. Ammons, Wake Forest University General Collection.)

Wake Forest was important to Archie Ammons. Here he met the woman he would marry and depend upon for the rest of his life. Renewing his connection to the campus in Winston-Salem gave him a way of keeping faith with North Carolina, which he always thought of as home. Phyllis believed that Wake Forest provided for him the bridge to the future, giving him the confidence to go to Berkeley to work at a nationally known university.

But it is still painful to think about how lonely Archie felt as a student at Wake Forest. Beyond bragging rights that he is one of our most distinguished graduates, how can we in other ways honor his legacy today?

A few years ago, Vendler, one of Ammons’ greatest admirers and a faculty member at Harvard, advised the Harvard undergraduate admissions office to look in its application pool for “the lonely and highly individual path” that students in the arts usually take. She pointed out that artists may not reveal themselves on their high school transcripts, and they may not come across well in an interview. In his poem called “Unsaid,” Ammons asked, “Have you listened for the things I have left out?”

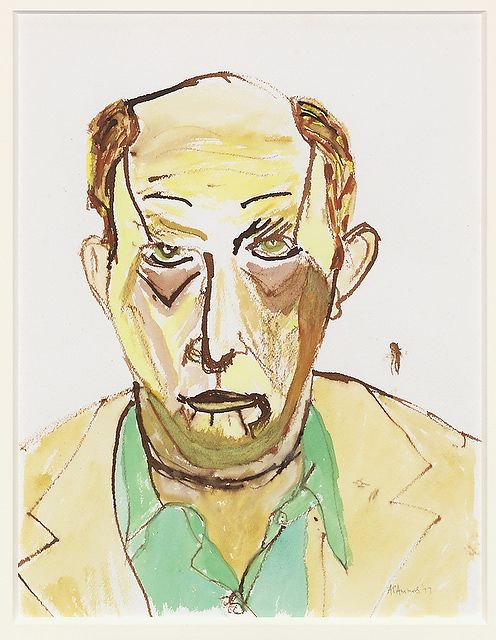

Watercolor self-portrait, 1977.<br /> (Paintings by Ammons, A.R. Ammons Collection, J.Y. Joyner Library, East Carolina University.)

We should remember Vendler’s advice and ask ourselves Archie’s question (the Wake Forest Admissions Office offers many guided tours and personal interviews to help make that possible). And we can pay particular attention to the shy student who never speaks in class, never asks for an appointment, is seldom seen walking away with friends.

It is also important to remember that students today feel economic differences, which sometimes are as severe as they were for Archie in 1946. He often felt poor in relation to other students, and it was a crippling feeling. He later made a good deal of money and boasted about it, winning prestigious prizes (he received one of the first MacArthur “genius grants”), but it never eased the pain of his memory of having felt so poor. The best tribute to the Ammons legacy at Wake Forest might be to nurture another great poet, but it might also be to make sure that being shy and poor is no barrier to feeling at home at Wake Forest.

If you don’t already know an Ammons poem, here is one to enjoy:

“STILL”

I said I will find what is lowly

and put the roots of my identity

down there:

each day I’ll wake up

and find the lowly nearby,

a handy focus and reminder,

a ready measure of my significance,

the voice by which I would be heard,

the wills, the kinds of selfishness

I could

freely adopt as my own:

but though I have looked everywhere,

I can find nothing

to give myself to:

everything is

magnificent with existence, is in

surfeit of glory:

nothing is diminished,

nothing has been diminished for me:

I said what is more lowly than the grass:

ah, underneath,

a ground-crust of dry-burnt moss:

I looked at it closely

and said this can be my habitat: but

nestling in I

found

below the brown exterior

green mechanisms beyond the intellect

awaiting resurrection in rain: so I got up

and ran saying there is nothing lowly in the universe:

I found a beggar:

he had stumps for legs: nobody was paying

him any attention: everybody went on by:

I nestled in and found his life:

there, love shook his body like a devastation:

I said

though I have looked everywhere

I can find nothing lowly

in the universe:

I whirled through transfigurations up and down,

transfigurations of size and shape and place:

at one sudden point came still,

stood in wonder:

moss, beggar, weed, tick, pine, self, magnificent

with being!

From The Selected Poems: 1951-1977, Expanded Edition, W.W. Norton & Company, Inc. Copyright © 1986 by A.R. Ammons

Emily Herring Wilson (MA ’62, P ’91, ’93) is a poet and biographer.