First lieutenant Verner Pike (’58, P ’84, ’89) was patrolling West Berlin, Germany, early on the morning of Aug. 13, 1961, when he noticed something odd just across the street in communist East Berlin. “Damn if they weren’t digging holes in the street and putting in posts and stringing up barbed wire,” he recalled.

It didn’t take Pike long to realize what East German police and Army units were doing: “They’re sealing off their part of the city.” He had watched that summer as more and more East Berliners simply walked to West Berlin, the last open portal to freedom from East Germany. But he also saw the growing stockpiles of construction material in East Berlin. In hindsight, “it had become obvious that if they didn’t do something, there wouldn’t be anybody left in East Berlin.”

It was the beginning of the Berlin Wall that would separate East and West Berlin until Nov. 9, 1989. (Scott Weltz (JD ’94), a Russian interpreter for the U.S. Army, was there when the Berlin Wall fell.)

“You drive a knife right through the middle of a city and the next day families are physically separated,” said Pike, who was a military police duty officer at the time. “It was unconscionable.”

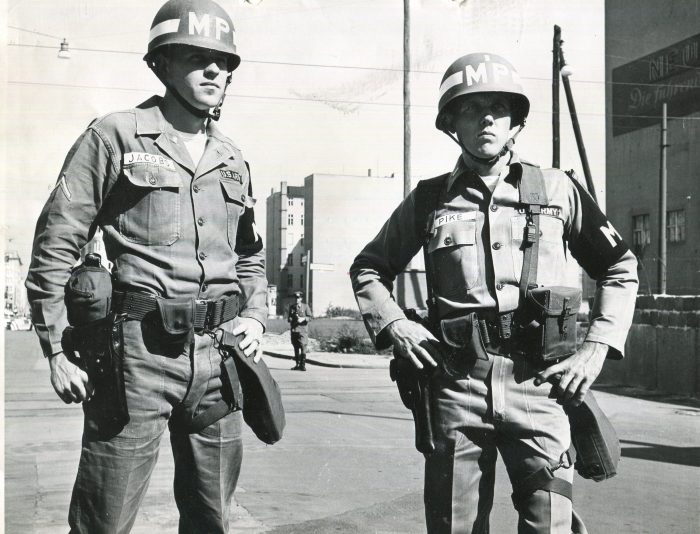

Verner Pike (at right) and his driver at the Berlin Wall in August 1961.

Pike had been assigned to part-time duty at the American golf course in Berlin that summer after his superiors learned that he had played golf at Wake Forest. Now he knew his golfing days were over. As the wall went up, he was placed in charge of a new checkpoint at the previously open border crossing. There was already a Checkpoint A, or Alpha, and a Checkpoint B, or Bravo, in West Berlin, so this new post was called Checkpoint C, or Checkpoint Charlie.

For the next 28 years, Checkpoint Charlie was “a beacon of freedom for East Germans,” Pike wrote in an e-book on his Berlin years, “Checkpoint Charlie: Hotspot of the Cold War.” “It was here that a force of American young men stood their ground against what President Reagan called ‘the evil empire,’ and they never flinched.”

Pike was just three years removed from Wake Forest — where he was a history major, a cheerleader, a Sig Ep and an announcer for WFDD — when he found himself in the middle of frequent flashpoints between American, Soviet and East German troops. It was a time when freedom depended on which side of the white line painted on the street — and the wall — you happened to be on.

“I’ve seen what people will do to be free,” Pike said recently from his retirement home in Cary, North Carolina.

Original "CP" Charlie platform manned by Verner Pike's MPs. The sign in the background -- "You are leaving the American sector" -- was in place before the wall was built, but took on new significance.

Pike, 79, retired as a colonel in 1988 after three decades in the Army including three tours in Germany and two in Vietnam, where he oversaw MPs in much of the country and fought drug couriers along the Vietnam-Laos border. He also served in Grenada and at the Pentagon; taught at West Point (where he taught a young cadet named Mike Krzyzewski) and the National Defense University in Washington, D.C.; and served as a military social aide in the Kennedy and Johnson administrations. His twin sons, Emery (’84, MBA ’92) and Damon (JD ’89), were born in Germany.

But it was his year at Checkpoint Charlie that left the most indelible mark. You had to be brash and bold to serve in Berlin, surrounded by hundreds of thousands of Soviet and East German troops. “We were a special breed of soldiers,” Pike said of his 287th MP Company and other soldiers that served there. “We were 110 miles behind communist lines. We were told to ‘stand tall and be proud.’ ”

As East Germany reinforced the rudimentary barbed-wire barricades with concrete walls, guard towers, tank traps and death strips, tensions along the wall escalated. West Berliners would often plead with him to help get relatives out of East Berlin. “There was nothing I could do,” he said. “It was horrible.”

A car squeezes through the Berlin Wall into East Berlin in December 1961.

Pike made frequent trips into East Berlin to escort U.S. diplomats or as a show of force with other MPs. During one trip, a young couple — probably a boyfriend and girlfriend — approached him and begged him to help them escape. He said he didn’t hesitate. “When you see the risks that people will take to be free, my instinct was if there’s a way to help, I’ll do it. I had a chance to help somebody, and I took the chance knowing full well that if I were caught I would have been court-martialed.”

He concealed the couple in duffel bags in the back of a military bus and headed back to West Berlin. When East German border guards stopped the bus, he refused to let them search it. “I told them I would talk only to a Soviet officer. You got 15 minutes,” Pike said he told the guards. After 15 minutes passed, Pike ordered the bus driver to continue into West Berlin. The young couple kissed the ground when they were safe inside West Berlin, he said. He never saw them again.

Pike once watched a man trying to flee East Germany push a bathtub, with a woman and baby inside, across a lake. East German border guards shot and killed the man. Pike said he ordered West Berlin border police to provide covering fire as MPs raced into the water to rescue the woman and baby. “It was just another day in the human drama of the Cold War in Berlin,” Pike wrote in his book.

Vern Pike, officer at left center, acting as an interpreter -- using the German he learned in high school and at Wake Forest -- and other Americans demand the release of a U.S. vehicle stopped by East German police in East Berlin.

In October 1961, Pike was alarmed to see a column of unmarked tanks in East Berlin head his way and stop just short of the border. U.S. tanks responded, and a standoff developed with Checkpoint Charlie in the crosshairs from both sides. American officials weren’t sure if the unmarked tanks were Soviet or East German.

The answer was crucial. Because of the post-World War II agreement that divided Berlin, only the U.S., Britain, France and the Soviet Union were allowed to assert military force in the city. If the tanks were East German, Pike said he feared the U.S. would have gone to war.

Pike was ordered to find out if the tanks were Soviet or East German. He drove into East Berlin and circled around the back of the line of the tanks. Seeing no one around one tank, he climbed inside and saw Russian script on the instrument panel and a Red Army newspaper.

“I still marvel at my luck that there wasn’t an armed Soviet in that tank,” Pike recalled. “A Soviet tanker shooting an American officer could have created an international incident.” He took the newspaper and reported back that the tanks were Soviet. After negotiations, both sides withdrew their tanks the next day.

American and Soviet tanks face off at Checkpoint Charlie in October 1961.

Pike was also the officer in charge of Steinstucken, a village near West Berlin. When the Berlin Wall was built, East Germany also sealed off Steinstucken, trapping residents. Pike was sent to the village to set up an MP post to reassure residents. Helicopters had to be used to ferry MPs and supplies in.

When five East Germans crashed a bus through the barbed wire fence to reach the town, Pike had to figure out how to get them to West Berlin. Driving wasn’t an option, so he dressed them as MPs and flew them out on a U.S. helicopter. When Soviet officials realized what had happened, they threatened to shoot down future helicopter flights from Steinstucken, he recalled.

Children wave at a U.S. helicopter leaving Steinstucken after dropping off MPs and supplies.

In February 1962, Pike had a supporting role in one of the most prominent prisoner exchanges of the Cold War. He escorted several Americans and captured Soviet spy Rudolf Abel to the Glienicke Bridge connecting West Berlin to Potsdam, East Germany. The bridge was often the site of prisoner swaps, often of spies, between the U.S. and Soviet Union during the Cold War.

He watched as the Americans walked to the middle of the bridge with Abel and several other men approached from the East German side. When the prisoner swap was finished, Pike was told to get the freed American prisoner to the airport as fast as he could. Only later was he told that the American was U-2 spy plane pilot Gary Powers, who was shot down and captured by Russia in 1960.

Pike still returns to Berlin frequently and has become an outspoken critic of the tourist-trap atmosphere at what was Checkpoint Charlie. “This to me is a sacred place,” he told a German reporter. “This was a place where you could see what it was like to be free, what people will do to be free. Freedom is not cheap.”

Aerial view of Checkpoint Charlie showing the guard post (lower left) and the white line, walls and death strips separating East Berlin from West Berlin.