On a perfect spring morning in southwest Florida, Syd Kitson (’81, P ’08) walks along the packed-dirt shoreline of a bluish-gray lake that fills a reclaimed rock quarry. Behind him is a barren lunar landscape of dirt and rock, disturbed only by the tracks of 40-ton earthmovers pushing dirt here and there. He pauses at the lake’s edge and looks across to a cluster of two-story buildings and dozens of houses under construction amid an oasis of palm trees.

“Look at the view,” Kitson says. “You’re witnessing the birth of a new town.”

Kitson, a developer who played football at Wake Forest and in the NFL, is building a futuristic-yet-throwback town on this somewhat remote site. His town of Babcock Ranch is rising from watermelon fields, sod farms and abandoned rock quarries on historic ranch land 20 miles northeast of Fort Myers. In a state peppered with retirement villages, he wants to create a community of single professionals, young couples with children, baby boomers, millennials and, yes, retirees.

A decade ago, Kitson revealed his dream to build a “town of the future”and “America’s first solar town.” Doggedly keeping his dream alive, Kitson has defied the odds, maneuvering his way through a tangle of negotiations that led to the single largest land conservation deal in Florida’s history, then outlasting the Great Recession.

“It takes a special kind of person to do this,” says Florida Power & Light Co. President and CEO Eric Silagy. “There are dreamers and doers, and Syd is both.”

Kitson, a 6′ 5″ tall, lanky 59-year-old known for his gridiron toughness and leadership, confesses, “Everybody thought I was crazy.” But he defied them and chased his vision for Babcock Ranch with gusto: “This was a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity, a once-in-many-lifetimes opportunity.”

“I thought Syd was a genius. How many people do you know who have the vision to start a new town? There’s only one person I know, and that's Syd Kitson.” — Tricia Duffy, Former Charlotte County (Florida) commissioner

The town of the future is rooted in Kitson’s past. Born in New Providence, New Jersey — population 12,000 — Sydney William Kitson was the middle child between two sisters in a close, lower-middle-class family. He grew up in what he fondly remembers as a “mansion,” a small house with one full bathroom and no air conditioning. His mother was a substitute teacher. His father was a metallurgist who sold coatings for jet engines and other industrial uses.

New Providence was the kind of hometown where “pretty much everybody knew everybody,” he says. He rode his bicycle to school, to the neighborhood pool and along his afternoon newspaper route. He played trombone, sang in the school choir and loved building houses and hotels on the board game Monopoly. But what he most loved was being outside, playing pickup games in the neighborhood and hiking and camping along the Appalachian Trail and in the Great Swamp National Wildlife Refuge in New Jersey.

Kitson, on the shore of Lake Babcock, planned his town of the future (background) to emphasize sustainability, nature, community, clean energy and technology, with a classic small-town feel.

He was a skinny wide receiver on his high school football team until he bulked up enough — thanks to eating five meals a day — to join the offensive line. By his senior year, college coaches were coming to New Providence to scout the hardworking tight end. When his top choice, Penn State, didn’t offer a scholarship, he headed south to Wake Forest — “the best decision I ever made.”

The kid who didn’t like to lose at football or Monopoly learned perseverance and patience at Wake Forest, playing on teams that won only seven games and lost 26 in his first three years. He played infrequently his freshman year before starting at tight end as a sophomore when the player ahead of him was injured. As a junior, he was heading for a breakout year — leading the ACC in receptions early in the season — when Coach John Mackovic (’65, P ’97) made an unusual request. Would he move to guard to shore up the offensive line?

He agreed to make the move for the good of the team. “Syd was, without a doubt, one of the most unselfish players I ever coached,” Mackovic says. “He was a terrific leader on the field. When you talk about leaders, you have to talk about work ethic, and he had a great work ethic.”

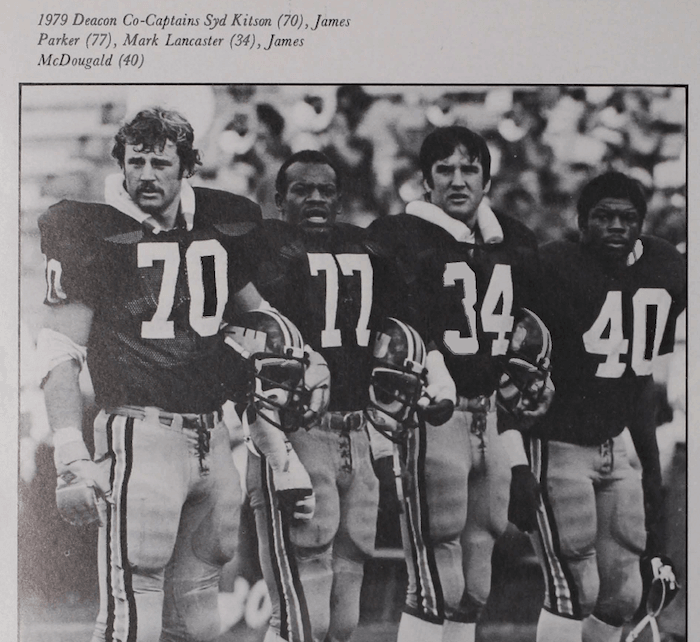

Kitson (from left), James Parker, Mark Lancaster and James McDougald were co-captains on the 1979 team that made it to the Tangerine Bowl.

Kitson flourished as one of the unsung guys in the trenches, blocking for quarterback Jay Venuto (’81) and opening up lanes for running back James McDougald (’80). “He worked his butt off,” says Venuto, then and now one of Kitson’s best friends.

The hard work of Kitson and his teammates paid off in 1979 when the “Cinderella Deacs” were invited to the Tangerine Bowl.

Weeks before he was supposed to graduate, Kitson experienced in real time the all-too-familiar senior nightmare. He learned he was one class short of finishing his economics major. He took responsibility and blamed himself, suffering through the worst part — telling his dad, who just couldn’t understand why his son wasn’t going to graduate.

He left Wake Forest without his degree after Green Bay drafted him in the third round of the 1980 NFL draft. But there was never a question he would finish. When the Packers’ season ended, Kitson returned to campus for the one-month January term to complete his course credits. It’s a message he preaches to young athletes: college is too important not to finish.

He went on to graduate with his sweetheart, Diane Hansen (’81), the woman he married. They would have a son, Tyler, who works for his dad, and a daughter, Lauren Leazer (’08, MSA ’09), who makes Charlotte her home.

Kitson’s 20-year plan calls for the construction of 19,500 homes, condominiums and apartments to house 50,000 residents.

Kitson spent four seasons with the Packers and one with Dallas. In the off seasons, he worked in landscaping and construction back home and volunteered in a real estate office to learn all he could about the business. An alumnus who was a real-estate developer had set him on the path to becoming a developer while he was still in college.

Though he can’t recall the man’s name now, Kitson remains grateful to him for giving him a tour of the neighborhoods he had built in Winston-Salem. “He was creating these great places where people were outside enjoying themselves,” Kitson recalls. “You could tell he was making a real difference in people’s lives. He had a passion that really struck me, and I said, ‘This is something that I want to do.’ ”

When lingering shoulder injuries forced Kitson to retire from the NFL in 1985, he moved back to New Jersey to work in real estate. He formed Kitson & Partners in 1999 and became known for turning around struggling golf course communities — Venuto even managed a course for him — and building high-end residential developments in New Jersey and later in Florida.

In 2004, in Florida, he found his dream property.

The first residents are moving into Babcock Ranch this winter.

For nearly a hundred years, the 91,000-acre Babcock Ranch, sprawling across Lee and Charlotte counties in southwest Florida, had been used for cattle ranching, logging, mining and farming. Environmentalists had long coveted the land to preserve its natural beauty and abundant wildlife — including the Florida panther, Florida black bear and other endangered species — and to protect an important wildlife corridor from Lake Okeechobee in the center part of the state to the Gulf of Mexico.

In the late 1990s, Babcock family members tried to sell the ranch to the state of Florida for a nature preserve. When negotiations fell through in 2004, environmentalists feared the property would be divided into five-acre ranchettes,” says Eric Draper, executive director of Audubon Florida.

“Then,” Draper says, “here comes this very tall, very charismatic former football player.”

With its old-growth forests, wetlands and Telegraph Swamp, the ranch was to Kitson “the most beautiful place I’d ever laid my eyes on.” He remembers watching as a flock of wild turkeys and a herd of deer walked by, as cattle grazed in the distance. The outdoorsman in him wanted to save the entire property. The businessman in him knew that wasn’t realistic; the property was going to be developed. It was only a question of how and by whom.

“He's a visionary who's doing something that no one else has done. He’s a force of nature, and he’s pleasant to work with. His word is his bond. If Syd says he’s going to do something, you can take it to the bank.” — Eric Silagy, President and CEO, Florida Power & Light Co.

He had never attempted a project so large and complex, fraught with environmental concerns and government regulations. Questioning whether he was up to the task, he turned to his closest adviser, his father, who was dying from esophageal cancer. His father assured his son that he had been working his whole life for an opportunity this big: what was there left to think about?

Kitson proposed a deal that would provide the state the land it wanted for the nature preserve while allowing him to develop a planned community on the remainder of the tract. Florida attorney Jack Peeples, who introduced Kitson to the Babcock family, says Kitson had the “creativity and courage” to put together a deal that many thought impossible. “This wasn’t a case where a big corporation came in. This was a guy coming in and saying, ‘I’d like to do that.’”

“This was critical,” says Kitson of Florida Power & Light Co.'s solar field adjacent to Babcock Ranch; 334,000 solar panels cover 440 acres.

But Kitson’s work was only beginning. For a year, he crisscrossed the state, selling his vision. With what Draper describes as Kitson’s “infectious, unrelenting optimism” and willingness to listen to all sides, he won the backing of Audubon Florida, Florida Wildlife Federation, 1000 Friends of Florida and other environmental groups.

Draper says Kitson showed how preservation and development could work together. “Syd was the one guy smart enough and confident enough to put the deal together. What he offered, in exchange for a new development, was the opportunity that more than 70,000 acres would never be developed. To me, the trade-off was worth it. Syd’s idea to create a green community was far superior to allowing rural sprawl.”

Kitson survived a late challenge from the national Sierra Club by agreeing to protect wildlife corridors and address other environmental concerns, which he says he had planned to do anyway. He won support from then-Gov. Jeb Bush and the Florida legislature, which appropriated the funds to buy the land for the nature preserve.

Kitson closed the deal in 2006 for what was reported at the time to be $700 million. He’s never released the purchase price but has since indicated it was closer to $500 million. The same day, he sold 73,000 acres to the state of Florida for $310 million and Lee County for $41 million to create the Babcock Ranch Preserve. It remains the single largest land conservation deal in the state’s history, both in total acreage and cost, according to the Florida Department of Environmental Protection.

“If you ask me what I’m most proud of, it would be that,” says Kitson.

“Babcock Ranch is a model of how we would like to see developments done, with a significant conservation commitment ... . Syd and his team (are) demonstrating that with good planning and implementation that the environment and the economy can go hand in hand.” — Manley Fuller, President and CEO, Florida Wildlife Federation

He began planning his town of the future on the remaining 18,000 acres, much of which had been used previously for mining and farming. He visited other planned communities — from Seaside and Celebration in Florida to Irvine Ranch in California — and listened to what local residents wanted to see in a new town. He envisioned a classic American hometown — one compact enough to bike or walk to work, school and shops — built from the ground up to emphasize sustainability, nature, community, clean energy and technology. He agreed to create wildlife corridors, restore historic waterways and leave half of the town acreage undeveloped as parks, wetlands and community gardens.

“This was an opportunity to create a new town but do it in the right way from the beginning to work with the environment and preserve most of the land and do something special,” he says.

Cattle ranching continues at Babcock Ranch as it has for 100 years. Cowboy Elton Langford leads a herd of cattle across land used as pasture within the town.

But he would have to wait.

In 2008, the Florida real estate market collapsed, delivering the worst blow. Kitson was forced to put his plans on hold, but he had come too far to give up his dream. “Never,” he says emphatically, before repeating John Mackovic’s halftime speech at the Wake Forest – Auburn game in 1979 when Wake Forest was trailing 38-20. “I could hear his words: ’Never, never, never, never, never give up!’ I think I repeated that to myself about 10,000 times. We never lost faith in our mission.”

Wake Forest came back to win, and, by many accounts in Florida, it appears Kitson is on his way.

Today, Kitson’s dream is becoming reality. A restaurant, a wellness center, an outfitters store, a general store and a business-incubator — all owned by Kitson — are open around the downtown main square. A public-charter elementary school, the first of several schools planned, welcomed 156 students from the surrounding area in August. Kitson wanted to have stores and a school open even before any residents arrived to show that he’s committed to building a town and not just another housing development.

The Founder’s Square downtown district includes a public-charter school (above), a restaurant (below), stores and a wellness center.

The first residents are moving in this winter to energy-efficient Craftsman and bungalow-style homes. Houses are set close to the street and have front porches to encourage neighbors to get out and meet one another. Trailheads lead to the nature preserve, which Kitson calls “the greatest amenity any planned community can have.”

Beneath the hometown charm is the technology that people expect today, including a gigabyte of fiber-optic connectivity and smart grid technology to monitor energy usage. He hopes residents will park their gas-powered cars and walk or bike to get around town or use electric cars or, coming soon, he says, driverless shuttles.

“Syd used his athletic instincts to become a principled businessman of character, competence, courage and decency, and you have to like the guy.” — Jack Peeples, Florida attorney

A 74.5-megawatt solar field is already generating enough clean energy to power the town when it’s finished. That goal wasn’t an easy one to fulfill. Kitson had to persuade Florida Power & Light to build a solar field when the company had no plans to build one there.

FPL President Silagy was stunned when Kitson offered to give the company the 440 acres it needed, adjacent to the town. “Who does that?” Silagy asks. “He’s a hard guy to say ’no’ to.”

Single family homes in Babcock Ranch start in the low $200,000s; condominiums and apartments are planned in future stages.

Kitson has emerged as a leader in the state in the decade since moving from New Jersey to West Palm Beach, about a two-hour drive straight across the state from Babcock Ranch. He’s past chair of the Florida Chamber of Commerce and a member of the Board of Governors of Florida’s State University System and the Florida Council of 100, a business development group.

Last year, he received the Ted Below Environmental Stewardship Award from Audubon of the Western Everglades for helping save the Babcock Ranch Preserve and for the “groundbreaking sustainability features” of the town of Babcock Ranch.

He’s just getting started. His 20-year master plan calls for the construction of 19,500 homes, condominiums and apartments, enough to house 50,000 residents, and 6 million square feet of business and commercial space.

As he looks over his new town from a balcony outside his second-floor office facing the town square, he poses a question: “Does this remind you of anything?” The palm-tree-lined square has tables and chairs, a splash pad for children, a band shell, a lakefront boardwalk and “solar trees” that power charging stations. He seems disappointed I don’t know the answer.

“The Quad!”

After a decade of planning and waiting, Kitson is seeing his vision come true.

If the resemblance isn’t clear at first, Kitson explains that he wants this to be the community’s gathering place, like the Quad at Wake Forest. Even before the first homeowners moved in, nearby residents filled the square for free concerts, farmers’ markets and exercise classes.

That’s what he envisioned years ago, creating a true sense of place. “When I sit here and … watch people in the restaurant, walking on the boardwalk, with their families playing in the splash pad, when they’re actually doing all of the things that I hoped that they would do, there is an incredible feeling that comes from that.”

He hopes the town will become a model – “a living laboratory”- for future planned communities to prove that development and conservation can go hand in hand.

“A community is a living, breathing place created by two things,” he says. “Most importantly, it’s the people, but it’s also about the place that you create, the place that allows people to find that community. It’s that neighborhood feeling that you have when you can go outside and play with the children. It’s a place where you have parks and safe areas to go for a walk or ride your bike. It’s about events. It’s churches and schools. It’s recreation and sports and the arts. All those things create community.”

It’s like the hometown he remembers. Just like he planned it.