The Vietnam War was raging when Forrest Hollifield (’68) joined Wake Forest’s ROTC program.

“Forrest figured that if he had to go, at least he would go as a commissioned officer,” says Dr. Tom Ginn (’68, MD ’75, P ’96, ’10), Hollifield’s roommate and Sigma Chi fraternity brother. “We were all trying to stay out of Vietnam for as long as possible.”

Hollifield was sent to Vietnam in April 1970 and joined the Sundowners, a small squad of aerial observers in the Army’s 108th Artillery. They flew with pilots in small, single-engine aircrafts called Bird Dogs.

Sundowner Joe Brett, who served with Hollifield, describes their mission. “We flew each day looking for enemy soldiers to kill by use of artillery, bombs or napalm. We were always being shot at. We were flying low and taking risks, and we enticed the enemy to shoot at us. That’s how we found them.”

Brett remembers Hollifield — by then a first lieutenant known as Sundowner Fox — as a true Southern gentleman. “He had it all together,” Brett says. “He was that guy from the South, and I was more of a loud guy at the bar from the Northeast.”

Ginn describes Hollifield, known as “Hollie,” as caring, kind, easygoing and funny. “He never had a bad word to say about anyone. He liked everyone,” Ginn says.

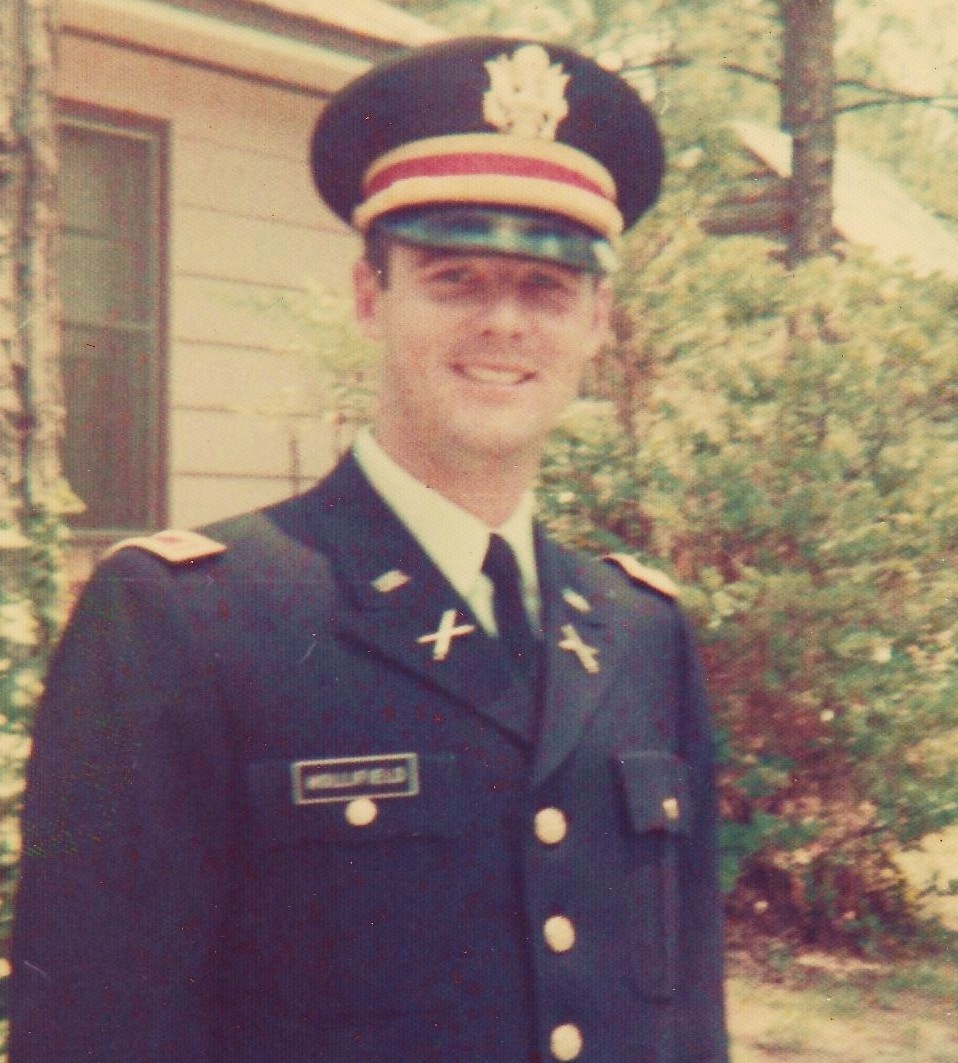

Forrest Hollifield ('68)

On July 29, 1970, Brett and Hollifield received their assignments for the next day. Brett didn’t like the pilot he was assigned to fly with and asked Hollifield to switch flights with him. Hollifield agreed.

The next day, Hollifield was killed in a crash caused by pilot error. He was 23. Brett saw Hollifield and the pilot lying dead amid the wreckage and watched as Hollifield was zipped into a body bag.

“I was like, ‘Oh, my God, that should be me.’ I was just shattered,” Brett says. “I was shame-filled and guilt-ridden. And then I started thinking that Forrest’s mother was going to get a telegram, and it’s going to be horrible. My only salvation was that my mother was not going to get a telegram.”

Hollifield grew up in Salisbury, North Carolina, and was the only child of Hughy and Wyndolyn Hollifield. Brett was encouraged to write a letter to the Hollifields but couldn’t bring himself to do it. “I said, ‘I can’t do that. What am I going to say? I just switched flights with your son, and he’s dead and I’m not.’”

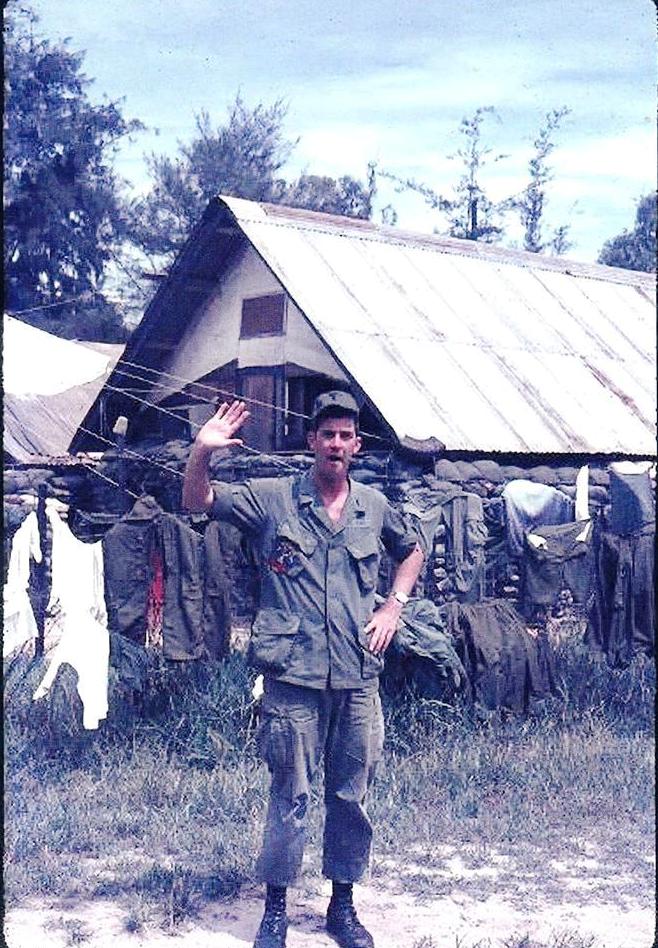

Joe Brett stands in the center of this group of Sundowners in Vietnam whose mission was to fly with pilots at low altitude, close to enemy fire, looking for targets to bomb. "We enticed the enemy to shoot at us. That’s how we found them," says Brett. Forrest Hollifield ('68) is not in this photo.

After Hollifield’s death, Brett became consumed with rage and went after the enemy with a vengeance. “Rage killing,” he says. “That was my release. I went out of my mind.”

The Hollifields’ great-niece, Karen Henderson, says her aunt and uncle, who have both passed away, experienced “terrible grief” after their son’s death. “I don’t think they ever got over it,” she says, noting that they had always hoped for grandchildren.

Ginn and a close-knit group of his fraternity brothers remain bitter over Hollifield’s death. “We were opposed to the war and felt like his life had been squandered,” he says.

Although Hollifield’s parents were “broken and sad,” Ginn says, they chose to remember their son as a patriot who died for his country. They endowed a Sigma Chi scholarship in their son’s name that continues annually at Wake Forest.

Ginn and several other fraternity members remained close with “Ma” and “Pa” Hollifield. He says they were like grandparents to his children and second parents to him and his wife, Judy (’68, P ’96, ’10). “I don’t know who adopted who,” he says with a laugh.

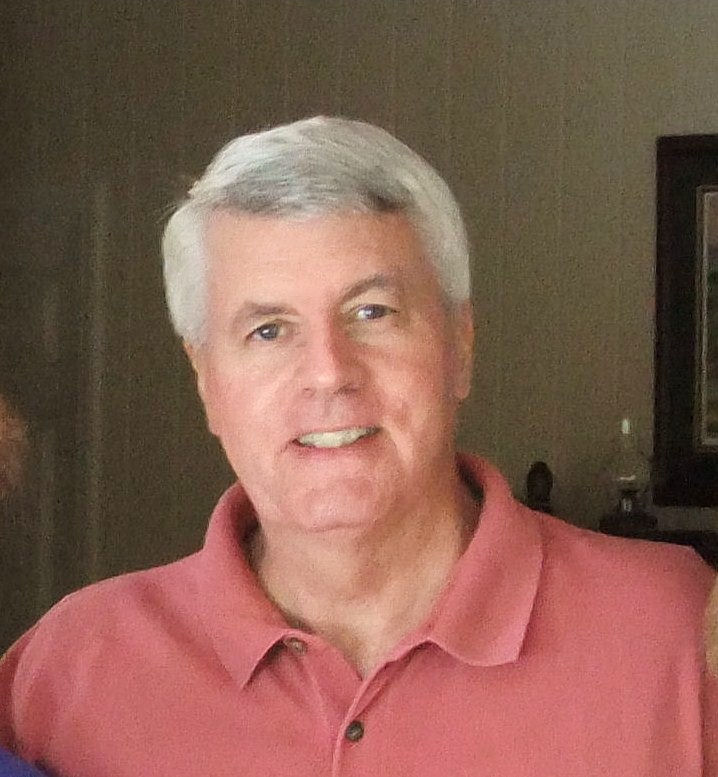

Dr. Tom Ginn (’68, MD ’75, P ’96, ’10)

As for Brett, he carried grief and shame deep within his soul. Although he had a successful career, he was an alcoholic who frequently experienced bouts of anger. “I was a binge drinker,” he admits. “I couldn’t be loved. I wasn’t worthy. I never felt good about myself, but I didn’t know why. I was alone and adrift.”

He tried to push aside the memories and visions of Hollifield that haunted him. “It hurt too much,” he says. “It was such a horrible thing to contemplate, and there was no solution.”

After checking himself into rehab in 1987, he got sober and found help from Alcoholics Anonymous. He finally married in 2005; his new wife, Cori, concerned about his anger, encouraged him to see a counselor.

Joe and Cori Brett

His therapist, Vietnam veteran Al Hoster, took him back to that tragic day in Vietnam. Brett was able to apologize to Hollifield and feel forgiveness from him. “(Hoster) found my buried moral wound and opened it,” Brett says.

Since that day, Brett has been on a mission to honor Hollifield’s memory and encourage other veterans to face their pain instead of burying it as he did.

As part of his healing journey, Brett traveled from his home in Arizona to Wake Forest in 2014 to meet with members of Sigma Chi. Director of Financial Aid Bill Wells (’74), a Sigma Chi who is now the fraternity’s adviser, arranged the visit and took Brett to a chapter meeting with about 60 brothers. Coincidentally, Wells’ brother knew Hollifield, as Brett learned when he called Wells to inquire about the Sigma Chi scholarship.

Joe Brett says goodbye to Phu Bai Combat Base in Vietnam.

Brett says he was filled with emotion as he stood in front of the fraternity brothers and eulogized Hollifield. Through tears, he told them about switching the flights. He gave them an etching of Hollifield’s name from the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, D.C., and a shadow box with a Sundowners patch and ribbons from Hollifield’s medals.

“They were blown away and deeply moved. They asked a lot of questions and showed so much compassion. I think it was really cathartic for him,” Wells says. “Joe made it out and Forrest didn’t. It’s one of those twists of fate that life is filled with.”

Brett says he called his therapist after the fraternity event and told him, “It’s done. I did it.” The next day, Brett walked the Wake Forest campus where he says he felt Hollifield’s presence. Since that day, Brett has traveled around the country sharing his story and honoring Hollifield.

Ginn, who lives in Winston-Salem, continues to mourn Hollifield, who was one of 58,000 Americans killed while serving in Vietnam. Ginn and his Sigma Chi brothers have kept Hollie’s memory alive.

In 2007, Ginn and others led an effort to add a marker in Hollifield’s name in the plaza at Lawrence Joel Veterans Memorial Coliseum. The granite markers recognize about 500 Forsyth County service members who were killed serving their country. Although Hollifield grew up in Salisbury, he was a native of Forsyth County.

Director of Financial Aid Bill Wells ('74) helped arrange for Joe Brett to speak to Sigma Chi fraternity about Forrest Hollifield ('68) and how Brett overcame his distress over Hollifield's death in Vietnam. Wells was a member of Sigma Chi and is its adviser now. His brother knew Hollifield.

Ginn heard Brett’s story for the first time during an interview for this story, and he was saddened by it. “It’s just another tragedy of the Vietnam War.”

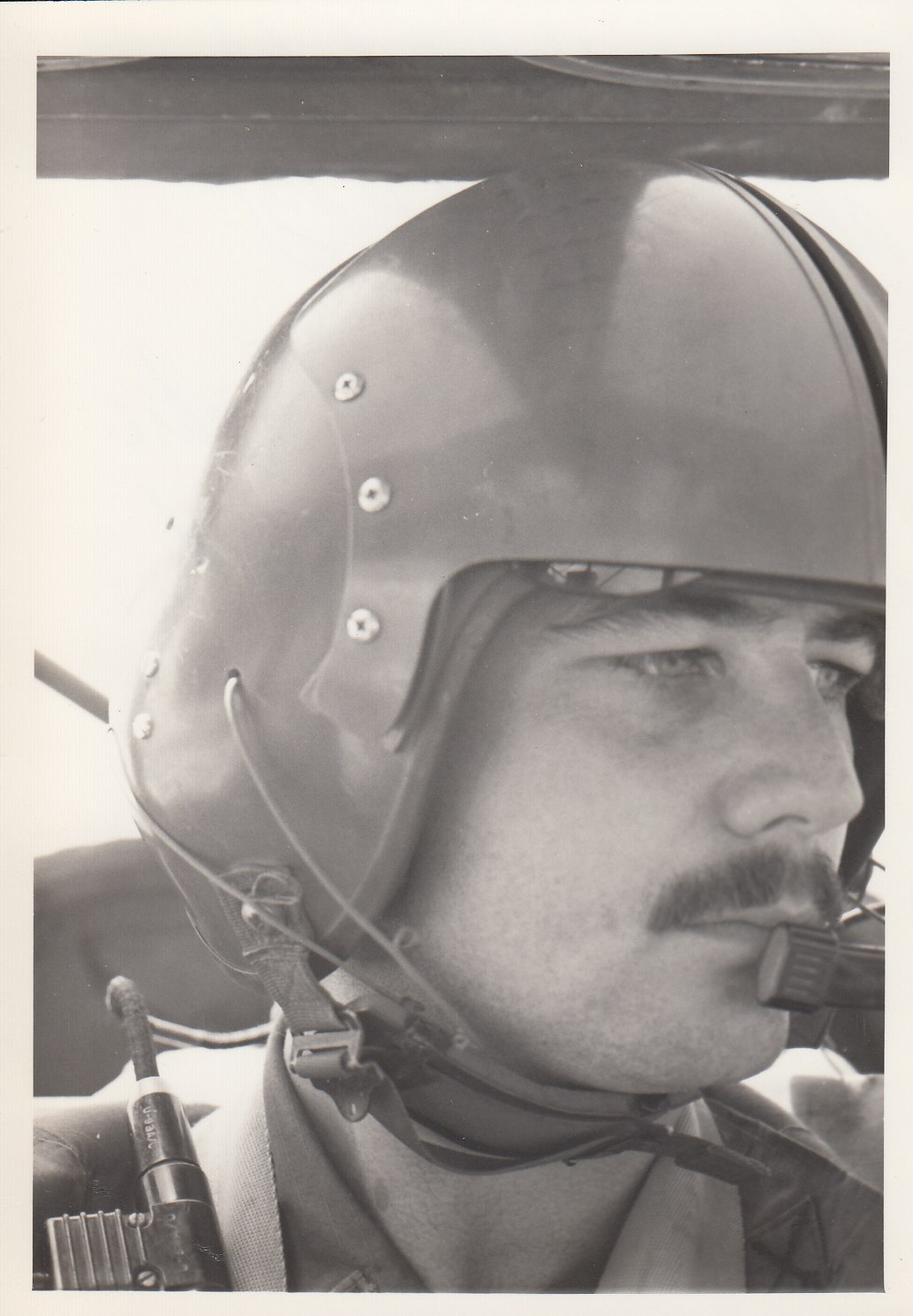

The interview also prompted Ginn to re-read the letters Hollifield had sent him from Vietnam. For 48 years, Ginn had been unable to bring himself to open them, but he decided the time was right. The picture of Hollifield in his flight helmet, shown here, was in one of those letters.

Forrest Hollifield ('68)

On Memorial Day, Ginn made his annual visit to place flags on the graves of Hollifield and his father, a World War II veteran who died in 1996. The flags were entrusted to Ginn after Hollifield’s mother died in 2001.

Ginn says he still talks to his roommate when he visits the grave, and this year he had a lot to say. “I stood beside Forrest’s grave and told him I had read the letters and about Joe Brett and his distress and guilt. It seemed appropriate to do so.”

Reading the letters was painful, but it brought him some measure of closure, Ginn says.

“He was as good a friend as I have ever had.”

Christine Graf is a freelance writer who also works for Soldier’s Heart, a nonprofit that serves veterans with post-traumatic stress.