When lifelong Wake Forest fan and author Ed Southern (’94) met his future wife, Jamie, a lifelong Alabama fan, their two worlds collided: basketball vs. football, a football underdog vs. a perennial national contender, the ACC vs. the SEC, North Carolina vs. the Deep South. That, and COVID-19, eventually led him on a journey — from Tuscaloosa, Alabama, to Tobacco Road, and from Alabama’s Bryant-Denny Stadium to Winston-Salem’s old Memorial Coliseum — to discover why sports mean so much to Southerners.

In his upcoming book, “Fight Songs: A Story of Love and Sports in a Complicated South” (Blair), he explores how Southern identity, culture and history shape our love of college sports, and how college sports shape Southerners’ identities and priorities. Southern, the executive director of the North Carolina Writers’ Network, writes about the connections and contradictions between the teams we root for and the places we plant our roots — with a good bit of Wake Forest history and sports history included, from football coach Peahead Walker to basketball coach Skip Prosser, and an entire chapter on “Barbecue with Mister Wake Forest,” Ed Wilson (’43, P ’91, ’93).

If you don’t understand Southern’s references to the Gaffney peach or “Sail with the Pilot,” you may not be a Southerner or an ole’ time ACC basketball fan. Alabama may have had more football success than Wake Forest, but he’s still “Proud to be a Deacon,” he writes.

This isn’t the book that you first envisioned. What book were you planning to write and what led you in a different direction?

My original plan was to write a short, fun essay about the inherent weirdness of being a lifelong Wake Forest fan who met, fell in love with and married an Alabama fan, just as Alabama again became a superpower (in football). When I was in school, Wake Forest got a bid to the (1992) Independence Bowl, and it was huge. We hadn’t been to a bowl game since 1979. We rolled not just the Quad but everything that we could reach with a roll of toilet paper. The season before Nick Saban was hired at Alabama, his predecessor, Mike Shula, took Alabama to the (2006) Independence Bowl . . . and they fired him. You’ve probably heard the Steely Dan song “Deacon Blues”: “They got a name for the winners in the world; I want a name when I lose. They call Alabama the Crimson Tide. Call me Deacon Blues.” Turns out they didn’t even know about Wake Forest.

I was going to write something fun about that. But once I got started, I began looking into the different cultures of North Carolina and Alabama, the so-called upper South and Deep South, the ways our histories diverge. Why is there such a religious fervor for college football in Alabama and the Deep South, but for college basketball in North Carolina? Then 2020 came along. I had been to Birmingham and Tuscaloosa for the weekend to do research for the book and came back in time for the ACC (men’s basketball) Tournament, planning to go. By the end of that week, of course, we had locked down. So the crisis presented by the pandemic, and the . . . rise of the Black Lives Matter movement, especially with the involvement of so many prominent college athletes, forced me to refocus the book.

"The Tournament ... was back in the Greensboro Coliseum, its ancestral home. I planned to drive over to Greensboro late Friday, go see what I could get a ticket for from the scalpers, grab a barbecue sandwich from Stamey’s across the street, and watch the Tournament in Greensboro as of old, as God and the Pilot intended, as every good North Carolinian should, once at least, and as often as possible. Then, all of a sudden, I couldn't."

You write a lot about ACC and Wake Forest sports history. What did you learn about Wake Forest that surprised you the most?

One of the things that surprised me was how intimately Wake Forest was involved in the creation of the ACC (in 1953). Jim Weaver (P ‘61) had been the Wake Forest athletic director before he became the first commissioner of the ACC. Dr. Tribble (Wake Forest President Harold W. Tribble LL.D. ’48, P ’55) was the only college president who was there at the creation of the ACC at the Sedgefield Inn (in Greensboro, North Carolina). (Before that) Wake Forest played in — and won — the first recorded college football game in the state (in 1888), against UNC. Wake Forest played in (and won) the first college basketball game (against Trinity, now Duke, in 1906) in North Carolina. So Wake Forest was instrumental in the creation of the ACC and the introduction of college sports to the state.

But would Wake Forest have even been in the ACC if we hadn’t already established those rivalries with our “Big 4” rivals, State, Carolina and Duke?

That’s just one of those counterfactual questions you can’t really answer. Would it have been a “Big 4” had Wake Forest not been in Wake Forest (North Carolina) at the time? If there weren’t so many Baptists in the state back then, would Wake Forest have been included in the “Big 4” in the first place? But then, had Wake Forest not moved to Winston-Salem, would we have been able to stay in the “Big 4”? Winston-Salem did open up the fan base and new resources.

Ed Southern is executive director of the North Carolina Writers’ Network and the author of "Fight Songs: A Story of Love and Sports in a Complicated South” and the short-story collection "Parlous Angels" and the editor of "The Jamestown Adventure" and "Voices of the American Revolution in the Carolinas." (Photo by Jess Blackstock)

You write about how Southern identity and history drive our passion for sports. You note that after Alabama defeated Penn in 1922, one writer said it was revenge for Gettysburg.

One of the most fascinating things that I discovered was the extent to which the military metaphors of football have been present since almost the very beginning of college football. The historian Amanda Brickell Bellows wrote that from the outset, football was seen as a way of toughening up young men. They were too young to have fought in the Civil War, but they had fathers and older brothers who did. They felt they had to prove themselves, and football was supposed to be a way to do that. That was a meaning ladled onto football from the beginning. So it wasn’t that the South invented those militaristic interpretations. But when Southern teams began beating Northern teams, they took it as this way to refight the Civil War.

That was true in the 1920s, and even in the 1950s and ’60s: when UNC won the 1957 national basketball championship with a team of New Yorkers, fans declared them “honorary Southerners.” But is it still true now, when so many players and coaches — even in the SEC — aren’t from the South? When the ACC includes Boston College and Notre Dame and Syracuse, and so many people living in the South now who weren’t born here? Are there other reasons that college football and basketball still inspire this level of passion and mania?

“The games we play and follow, the sports we set our seasons by and turned into booming industries, reflect who we are and who we want to be or seem to be, where we have come from and where we want to go. They are both the projection looking forward and the mirrored image looking back.”

Switching gears to your job as executive director of the North Carolina Writers’ Network. Since you’re in touch with writers across the state, what has the last year and a half been like for writers?

Some have been tremendously productive, because writing was their refuge from the anxieties of the past year. I know other writers who simply have not been able to find the bandwidth to write, because they’ve been so preoccupied with everything going on in the country. I feel especially bad for the many authors who had books come out in the past year. A number of authors had their debut books coming out with a lot of buzz, and they were going to be doing great (book) tours, and then it was gone. Online events are great — booksellers and authors figured out online events fairly quickly — but it’s just not the same as in-person events.

Are there any books about the pandemic that you would recommend, or is it too early?

Michael Lewis’ book “The Premonition: A Pandemic Story” is about the pandemic. I don’t know of any others, at least not yet. There have been some fantastic books come out in the last year, though. Matt Gallagher’s (’05) novel “Empire City” is terrific and rather frightening in its relevance. A North Carolina author and member of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians, Annette Saunooke Clapsaddle, published her debut novel, “Even As We Breathe.” It’s set in the North Carolina mountains during the 1940s. It’s one of those fantastic debuts that far too many people missed because she wasn’t able to do book tours. My favorite new book of last year was “Piranesi,” by Susanna Clarke, a British writer. Also, Hilary Mantel published the final installment in the Thomas Cromwell trilogy, “The Mirror & the Light,” last year.

When we look back on 2020 and 2021, what mark will the pandemic, Black Lives Matter, political turmoil and social unrest leave on literature of this era?

I hope it will be a lasting mark and a considered one. It would be awfully easy to sensationalize everything that’s happened the last year. I hope that writers will really reckon with and grapple with everything that’s happened. It’s interesting that so much of the literature in the 1920s and even in the 1930s was marked by the experience of World War I. But there’s virtually no mention of the great influenza of 1918 and 1919. It’s something that killed millions of people around the world. Will that be the case again? Will we act like the pandemic never happened? Will we forget about the Black Lives Matter movement?

To use the 1898 Wilmington coup as an example, it was completely covered up in history books and the official record. For decades, people had no idea what had happened, and if they did know, they heard that it was a riot and both sides were at fault. But through all that time, there was Charles W. Chesnutt’s novel, “The Marrow of Tradition” (1901). It was a fictionalized version of the Wilmington coup that wasn’t meant to be a history, but the memorialization of the causes and the effects. All those years that the official history was silenced and hidden, that novel was still out there.

I think creative writers — and by that, I mean anyone who’s attempting to do more than simply chronicle events, anyone who’s trying to apply imagination to it, a poet or a novelist or a playwright — I think creative writers at their best are able to, not just record, but memorialize our reactions to events. I hope creative writers will grapple with this.

“Fight Songs: A Story of Love and Sports in a Complicated South” is available for preorder at Bookmarks in Winston-Salem, Amazon, Barnes & Noble and other retailers.

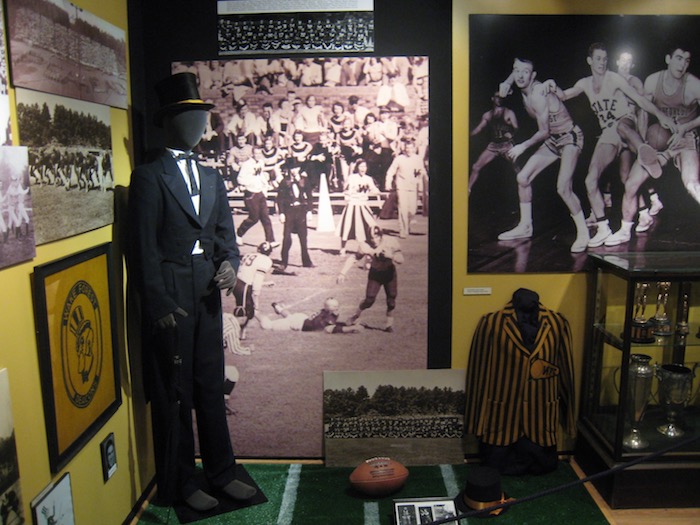

Display of sports memorabilia at the Wake Forest Historical Museum in Wake Forest, North Carolina.