Retired U.S. Army Col. John C. “Jay” Waters (’87) must have been quite a sight as he rode his bicycle into the Pacific Ocean on a Native American reservation in La Push, Washington, on a cold, foggy day in early September — and was promptly knocked over by a wave.

Wearing a bright orange shirt, multicolor jersey, biker shorts and black face mask and sporting a gray wooly beard, looking a bit like “the guy from ‘Back to the Future,’ the mad scientist,” by his own description, he recovered to raise his bike high above his head.

Waters was celebrating the end of a 106-day, 3,829-mile bicycle ride across the country sponsored by the veteran-run Warrior Expeditions. His sister, Sharon, Vietnam veterans from VFW Post 9106 in Forks, Washington, and members of the Quileute Tribe — which granted him permission to cross their tribal lands to the ocean — greeted him.

The finish line for Jay Waters.

When he left from the U.S. Capitol with four other veterans on May 26, Waters set a personal goal for the trip: Not to get to the West Coast in record time, but to stop at every American Legion, VFW and AMVETS post, Marine Corps League and other veterans’ organizations and memorials along the way. He chronicled many of those stops with selfies on Facebook, always with a large smile on his face and a thumbs-up, even as the miles piled up and his beard grew longer.

“Everywhere from Maryland to Washington state, I probably stopped at over 200 of them. You can’t just say ‘hi’ for five minutes, take a picture and leave. You got to go in and have a hamburger or a beer or a Coke,” he said in a Zoom interview from his home in Alexandria, Virginia. “I found it especially rewarding to meet up with the previous generations, like the World War II, Korean War and especially Vietnam War veterans, to thank them for paving the way and their amazing service.”

In a way, the trip was just a long-distance version of what Waters has been doing for several years, paying tribute to veterans, whether it’s honoring the fallen at Arlington National Cemetery or preserving veterans’ stories for future generations.

Jay Waters, far left, and four other veterans leave on their cross-country bike trip from the U.S. Capitol on May 26.<br />

Wake Forest Magazine last met up with Waters in 2014 when he was at Arlington. As executive officer for the Army National Military Cemeteries program, he was responsible for Arlington and the Soldiers’ and Airmens’ Home cemeteries in the Washington, D.C., area, and 38 smaller, less well-known cemeteries nationwide, including those at Army posts and eight for prisoners of war.

A 30-year Army veteran, Waters served in Desert Shield/Desert Storm, Afghanistan, Rwanda, Liberia and Italy. After serving at Arlington, he was executive director for the U.S. Army Physical Disability Agency in Arlington, Virginia, until retiring in 2017. Since then, he’s interviewed more than 100 combat veterans for oral history videos for the Americans in Wartime Experience (more on that later).

His coast-to-coast bike ride — delayed for a year because of COVID — was made possible by Warrior Expeditions, a nonprofit that provides long-distance excursions to help combat veterans transition from wartime duty to civilian life. The excursions include the cross-country bike trek, a Mississippi River kayak trip and hikes on the Appalachian Trail, the Mountains to the Sea Trail in North Carolina and other trails.

A long, lonesome highway in Guthrie Center, Iowa;

It was Waters’ second excursion sponsored by Warrior Expeditions. In 2019, he completed a three-month, solo 800-mile hike on the Arizona Trail, overcoming extreme heat, lack of water, rattlesnakes, Gila monsters, cougars and other perils. He was looking for one more adventure when he signed up for the cross-country bike trip, even though he wasn’t an experienced cyclist.

In the military, “you have this great career where you’re doing important things every day and you feel like a rock star. Then you retire. I kind of wanted to have one more big adventure,” he said. “But more importantly, it was an opportunity to tell the story about the Warrior Expeditions program, because it’s done a lot for me and countless other military veterans.”

Warrior Expeditions provided his Trek 920 bike and most of his gear, including food, a tent, air mattress, water-filtration system, stove and bear spray. (The final bear count was two, a mother and cub in Yellowstone National Park. It was also in Yellowstone that he had to jump into the bed of a stranger’s pickup truck to escape approaching bison. Dogs proved to be a greater threat than wildlife.)

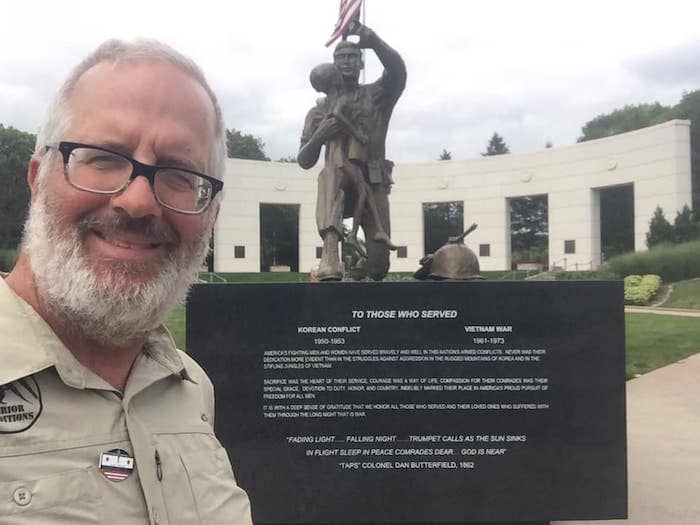

A Korean/Vietnam Memorial in Omaha, Nebraska;

Waters rode through 11 states on bike trails, canal paths, back roads, treacherous interstates and the partially completed Great American Rail-Trail. The rail-trail, which is about 53% complete, will eventually link existing bike trails and abandoned rail lines with new trails to form a contiguous route between Washington, D.C., and Washington state. He had only two minor crashes, but worried constantly about getting hit by a car or truck.

The physical aspect of a cross-country bike ride was, of course, challenging, but the mental side may have been more daunting, he said. He didn’t think about riding 65 miles a day; he’d break that into smaller and smaller pieces, until his goal was something like, ride 15 miles and take a break, ride another 10 miles and stop and talk to some locals and so on. “And just like that, you knocked out 65 miles on what would end up feeling like a fairly ‘easy’ and regular day,” he said. “Repeat each day for the next 106 days.”

That strategy came from something he learned at Wake Forest, Greek philosopher Zeno’s dichotomy. (Waters was an economics major, but doesn’t recall in which class he learned Zeno’s dichotomy.) “I (broke) the trip up mentally into halves and sections so as not to get overwhelmed by the sheer distance of nearly 4,000 miles. I always remembered Zeno’s Paradox about motion and how every trip could be infinitely divided into half and then half again (and so on). It kept me mentally occupied.”

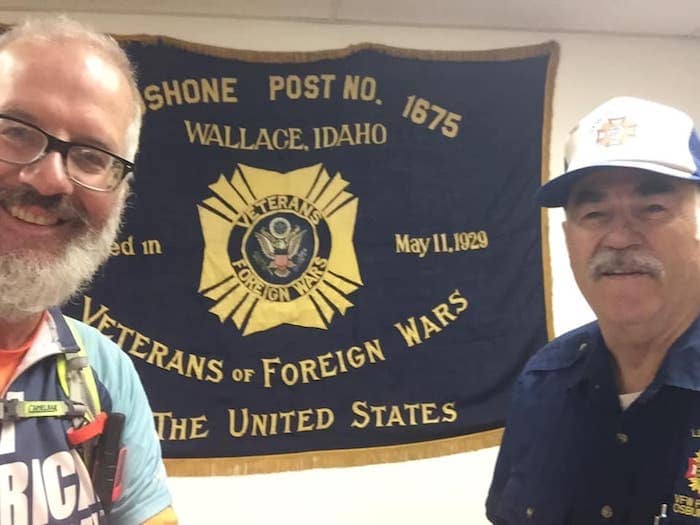

Waters at the VFW Post in Wallace, Idaho, with Post Adjutant Joseph Wallace (no relation to the town)

All five veterans on the trip left Washington, D.C., at the same time, but they rode at their own pace. Waters was by himself most of the time because of the number of stops he made, but he was never really alone, he said.

“When I got to a small town or a big town, I’m not going to stay in my tent or in my hotel or cabin or wherever I’m staying. I’m going to be out in the town meeting the locals, hearing their stories, finding out what I can about the town.”

He posted stories on his Facebook page almost every night about the people he met and the “rich, American experiences” in small towns off the beaten path. A gregarious sort, he had no trouble making new friends, whether it was a Gold Star family in Nebraska, a 90-year-old Korean War veteran in Illinois, an 86-year-old Vietnam vet in Washington state or fellow Wake Forest graduate Will Kennedy (’99) and his family in Yellowstone National Park.

He just happened to be passing through O’Neill, Nebraska, on the day of a parade honoring a World War II Navy machinist whose remains had just been identified and returned to his hometown. Waters stayed for the parade to pay his respects. He found himself in towns so small, and trusting, that paying for motels or supplies was on the honor system; take a room or what you need and leave some money on the counter.

He spent Memorial Day at an American Legion post in Frostburg, Maryland, and observed the D-Day anniversary at a Legion post in Scio, Ohio. Along the Cowboy Trail in Nebraska, he met cattle ranchers and farmers. In Wyoming, he met a native of Bucharest, Romania, who was shocked that Waters could speak Romanian. (He was stationed in Romania in 2007.)

Waters’ wife, Anna, biked with him for a couple of days in western Montana. He met up with his older son, Albert, in Canal Fulton, Ohio. Early in his trip, he posted a photo on Facebook of a Nucor steel plant in Ohio with a “Thank you veterans” sign on the building. Officials at Nucor saw the post, and several weeks later as Waters was riding through Norfolk, Nebraska, they invited him to stop and tour Nucor’s steel plant there.

As he rode east to west, strangers followed his journey and started looking for him and looking out for him. As he rode into towns, he’d often be greeted by locals offering to show him around their town or provide a home-cooked meal or a place to spend the night.

“One of the things that I found very empowering … You’re on a bicycle and you don’t fit into that town and you look different,” he said. “But you say to someone, ‘Can you help me?’ That’s a powerful phrase. And they will. You simply ask for directions or whatever it is. But that opens the door. It’s a leap of faith for two strangers.”

After he rode into the Pacific Ocean, Warrior Expeditions claimed his bike to ready it for another veteran’s trip. Waters flew back home to Virginia and resumed work on the project close to his heart, interviewing combat veterans for oral history videos for the Americans in Wartime Experience.

Jay Waters in Butte, Montana

It’s one of the ways he can give back. “As a Desert Storm and Afghanistan veteran, I like meeting the Vietnam veterans, the Korean War veterans, the World War II veterans,” he said. “Most of us (conducting the interviews) are combat veterans, so we have the immediate rapport and trust with the veterans. He or she might tell us some stories that they haven’t talked about before. We get a lot of feedback from families, like ‘dad or grandpa never talked about their time in Germany or Okinawa.’”

Waters isn’t planning another long bike ride, but he hopes to organize a long-distance hike, from Washington, D.C., to Winston-Salem with other Wake Forest veterans. Wherever his next adventure takes him, he’ll take an important lesson from his coast-to-coast bike ride with him.

“Meeting wonderful, kindhearted people from all walks of life left a strong impression and is a great reminder that there are still so many good people out there willing to help you.”

Leaving Yellowstone National Park on the road to Gardiner, Montana.