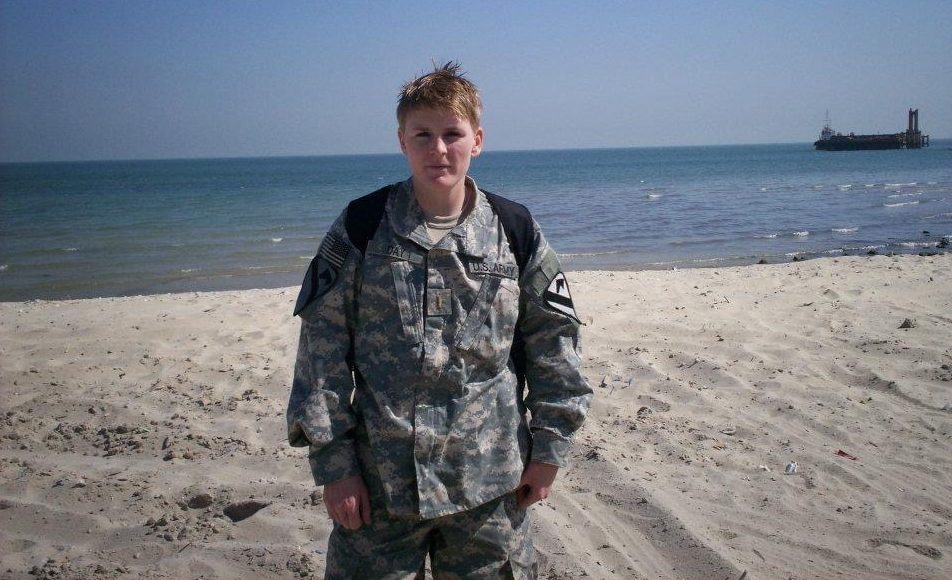

Sara Day ('01) runs in the Lincoln (Nebraska) National Guard Marathon, coming in second overall and first in her age group, in May 2012 when she was on leave from Kuwait. Her time of 3 hours 3 minutes averaged 6.58 per mile. <br />

Next month’s 21st anniversary of the terrorist attacks of 9/11 will commemorate a life-changing moment for many Americans. For Sara Day (‘01), it was a moment in which she suddenly faced a choice between her values and her passion.

Day had just graduated in May from Wake Forest as a three-time All-American distance runner. She had finished second in the nation in the 10,000-meter run at the NCAA Outdoor Track & Field Championships. She was poised to make a serious bid for the 2004 Olympics and to turn her passion for running into a career.

As she drove home on the morning of Sept. 11, 2001, from an overnight stay at her mother’s home in Clemmons, North Carolina, she heard the news on the radio. A plane had crashed into one of the Twin Towers of the World Trade Center in Manhattan.

Another plane hit the other tower, and both towers collapsed.

“I was, like, ‘What’s going on? Are we being invaded or something?’” Day recalls.

The military had never played a part in her dreams; she hadn’t been interested when the U.S. Naval Academy tried to recruit her. But she enlisted in the U.S. Army. She felt called to duty, to protect her country. By January 2002 she was in basic training.

“I know there’s mixed perceptions of the military, but in my eyes, I was still fighting for social justice.”

An athlete had given her a card earlier about a military runners program for nationally ranked athletes. She hoped she would be assigned to it after boot camp to keep running toward the Olympics, but the recruiters hadn’t heard of the program and couldn’t guarantee it. For her to honor the American flag in an immediate way, she had to risk losing a chance to honor it atop an Olympic podium.

Sept. 11, 2001, brought just the first of many surprising shifts that would follow in Day’s life. An injury ended her Olympic hopes but not her ability to run, even today. On this Sept. 11 she will not only remember 9/11 but also two decades of military service. Today she is Lt. Col. Sara Day of the U.S. Army Reserve, an officer in the training directorate at U.S. Army Forces Command, or FORSCOM, at Fort Bragg, North Carolina.

She is proud of her years in the military, of serving in the Iraq War. Besides loyalty to her nation, a desire to help others has also guided her life. She majored in sociology at Wake Forest with a mind toward going into social work, particularly helping abused women and children, after or in lieu of a running career. She says the military has surprised her with the number of opportunities it has offered her to carry out a personal version of Pro Humanitate, from building a school in an African village to supporting young troops.

“I know there’s mixed perceptions of the military, but in my eyes, I was still fighting for social justice,” Day says.

From fast fish in a small pond

Day took a roundabout route to running and to Wake Forest. As a youngster, she ran a mile each way to the school bus stop, but the running bug seriously took hold whe she joined the cross-country team at Ledford High School in Thomasville, North Carolina. Running “just became my thing. I started winning races.”

In 1997, she accepted a full scholarship to High Point University, where she could run the nine miles to her mother’s home at the time. But when she discovered the program hadn’t yet moved up to Division 1 in the NCAA, “I kind of became a free agent.”

Her mother, who worked at Bank of America in Winston-Salem, called the track & field program at Wake Forest, despite her daughter’s insistence that her single mom couldn’t afford it. Day almost backed out of the interview but arrived on campus to a tour of amazing facilities and a full scholarship offer. “I was, ‘Wow, where do I sign?’”

Her beginning didn’t go smoothly. She came in as a junior but had lost a semester of credit and needed to catch up. “At High Point, I had never really been to parties. I was a very strict athlete. When I got to Wake, people were inviting me to these parties. I think I got a little bit too wrapped up in that, and I wasn’t getting enough sleep, and I definitely wasn’t getting the nutrition.”

At High Point, “I was the big fish in a very small pond.” At Wake, she was “a very small fish.” She was not as fast as All-Americans Janelle Kraus-Nadeau (’01) and Jill Snyder Kerr (’00, MAEd ’01) or the other top talent.

She says then-Coach Annie Bennett sat her down and told her, “Sara, in order to be a champion, you have to hang out with champions.”

Jill Snyder Kerr (’00, MAEd ’01)

Day listened. She says she began to emulate everything the star runners did. “They were my friends. I didn’t ask them anything. I guess I was kind of creepy, but maybe I studied them. We still had fun, but we didn’t have fun on the night before a long run.

“The next year I was a lot faster. I went pretty much from nobody to three-time All-American.”

Kerr, a five-time All-American, and Day became friends. “What really comes to mind is her work ethic,” says Kerr, a former assistant coach at Wake Forest who still consults in Massachusetts. “And her loyalty as a friend and teammate was just amazing. She’s that friend you call when you’re in trouble.”

Bennett says Day wanted to be good, worked hard and ran smart. “I coached a lot of people with more raw talent. The talent she had was to take a risk, be coachable, listen to her supervisor. She always had her head up to look at a bigger vision.”

“The next year I was a lot faster. I went pretty much from nobody to three-time All-American.”

Terrorists attack

After graduation, Day was working at High Point University as director of resident advisers, with enough from her small salary, room and board and a few sponsorships to pay for races to prepare for the Olympics. “I wanted to be standing tall and proud when the national anthem came on, whether it was on a podium or what,” she says.

Then came Sept. 11, when Islamic terrorists from al-Qaida flew two planes into the World Trade Center, crashed a plane into the Pentagon and hijacked United Airlines Flight 93, which crashed in a Pennsylvania field as passengers rushed the hijackers. The attacks killed 2,977 people. The United States launched military retaliation in Afghanistan, where Osama Bin Laden had directed suicide missions against America.

Army recruiters urged Day to enlist for officer training because of her Wake Forest degree, but the 18-month training would have detracted from her three years to prepare for Olympic trials. Disappointed by her post-basic training assignment to South Korea, she called the friend in the military running program. It worked. The Army sent her to a program at Stanford University.

“I wanted to be standing tall and proud when the national anthem came on, whether it was on a podium or what.”

A pelvic fracture

She felt prepared for California.

“I was only two seconds off the Olympic trial standard (for 10k) when I left Wake Forest,” Day says. “It was kind of a segue for the military. I was already trained.”

But two weeks after Day arrived, the well-known coach left because of his wife’s illness. Day, in an Army uniform, faced war protesters on the streets of Palo Alto. “I was having people ask me in California, ‘You seem like you’re intelligent. Why are you in the Army?’ And I’m like, ‘There are intelligent people in the Army. It is a profession.’

She was unhappy.

Worse, she had developed a pelvic stress fracture, which could kill her if it cracked, after she was assigned to run 125 miles a week. She had never run more than 80 a week. Her Wake Forest coach, Annie Bennett, offered to coach Sara for free, and the Army agreed to send Day to North Carolina with Bennett. “Annie nursed me back to health but nowhere close to where I needed to be (in time for the 2004 Olympic trials).”

The Army ordered Day back to regular duty. “It pretty much destroyed me. It’s kind of like losing a relationship; running was my relationship.”

Into leadership and the desert

After assignments around the country, Day became an officer in 2005 and found herself sitting on a duffle bag in the Iraq desert with a platoon of 20 young people reporting to her. She began to see ways to offer assistance.

“In Iraq, you’d see the little kids that were affected by this man who was in power (dictator Saddam Hussein),” Day says.

She mentored young troops, many just teens ordered to a second grueling tour of duty. She called them “my kids.”

“They still send Christmas cards. We’re still in touch on Facebook,” she says.

It was a dangerous time.

In 2007, a bombing at her cafeteria and sleeping quarters at the Camp Victory complex in Baghdad killed two and injured 38. Day was away with her platoon for a flag football game, but her mother saw the news on “Good Morning America.”

“I had to … get a dial out so I could call my mom and say, ‘I’m okay. Don’t freak out.’”

She still managed to run, accompanied for security by Maj. Christine Cooper, at the time a staff sergeant in Day’s platoon. Cooper rode along on a bicycle with frozen water bags that Day could drink as the ice melted in the blistering heat.

Assigned to Kuwait with no available running buddy, she trained for a marathon inside on a treadmill. She made the All-Army Marathon team and took leave for races.

Running in Kuwait

Finding a military home for helping

Day is gay, and the military kicked out many of her friends because of the “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” policy.

“The Army’s all about integrity and telling the truth. It’s almost like telling you, ‘You have to be honest, but you can’t tell us this major part of your life.’” Her colleagues and subordinates did not care that she is gay, “but my leadership really had a problem with it. I was tired of it.”

She decided to resign. When she was asked in her exit interview whether she was ready to take off the uniform and be a regular person, her answer was, “No, I love this uniform.”

Instead, she was offered a transfer to the North Carolina National Guard in Greensboro, near her family. (“I’m a mom’s girl,” she says.) Guard leadership welcomed her. “As long as you were confident and you were doing your job, they just didn’t care,” she says.

From 2008 to 2020, the Guard opened more ways for her to help others: on campuses, where she made sure professors accommodated students’ ROTC duties; as deputy director of a military unemployment center working alongside social workers to aid struggling veterans and families.

She kept pursuing education. She earned a second bachelor’s degree, in information technology. She earned a master’s degree in cyber security management and another in information technology and network security. She attributes her 3.92 and 4.0 grade point averages in graduate studies to the discipline learned at Wake Forest, where “some of the classes were tougher than any of my master’s classes.”

In 2020, she moved to FORSCOM. She was promoted to lieutenant colonel in the Army Reserve in June 2021. She works on logistics for war scenario training.

And she kept running. She made the 2012-1013 All Guard Marathon Team. She won the All American Marathon at Fort Bragg twice, most recently in 2019 before the pandemic disrupted the event.

“My running is what sets me apart in the military. I’m not a very good shooter … but at least I can run.”

She can retire in four years. With her military pension and GI benefits, she can afford to pursue another master’s and become a social worker after all, even if the pay is low.

“It really came all the way back to what I wanted to do when I was at Wake Forest. … I wanted to help people.”

“I coached a lot of people with more raw talent. The talent she had was to take a risk, be coachable, listen to her supervisor. She always had her head up to look at a bigger vision.”