With his eyes focused intently, in the way people do when they’re figuring something out, Spencer Giglio (’21, MD ’25) looks down and processes how to speak his next sentence in Spanish with his 10-year-old patient.

Giglio is a second-year medical student in the MAESTRO certificate program in the Wake Forest School of Medicine. The program was founded as an innovative collaboration between a pediatrician in the medical school and an award-winning Spanish professor on the Reynolda campus. The goal is to train future doctors how best to treat patients who primarily speak Spanish. These patients make up a growing proportion of those in the United States and locally who are subject to health inequities.

The program’s first class of nine medical students will graduate this spring, and the program is winning praise for its deep, four-year process and its rare merging of language pedagogy and medical education.

Giglio practices a conversation with a fictional young patient on a Friday morning in September in a small medical school office in downtown Winston-Salem. Playing the verbal role of the 10-year-old with asthma is Mariana Pardy, a veteran hospital interpreter who joined MAESTRO (Medical Applied Education in Spanish through Training, Resources and Overlearning) as an instructor in January 2022.

Giglio uses prompts from a document with a case description and instructions on dealing with the patient. Pardy gives him feedback on his language use — (“Your Spanish is good. I feel like your grammar has improved. … Keep working on verb tenses.”) — and how best to work with patients from a different culture.

For example, she tells him, instead of pronouncing medications such as albuterol in English in his throaty, native California accent, say the word with a crisp Spanish accent “because that’s actually how the patient would read it.”

She tells Giglio he did well explaining the difference between the patient’s everyday inhaler and the emergency one. She cautions him that referring to the inhaler using the verb “manejar” for “to handle” could confuse a 10-year-old. That’s because in Spanish, that verb used alone could mean “to operate,” as in a car.

“It would have been a really weird word. (He might say), ‘I don’t drive; I’m 10 years old,’” says Pardy, a native of Mexico who began ad-hoc interpreting for her family when she was a teenager.

For Giglio, this is all a lot to think about. He majored in math, with a minor in chemistry, at Wake Forest. He began developing his Spanish in high school, with volunteer work and mission trips abroad, but with a patient he must speak with precision, in a natural speed, while keeping a formal but friendly tone, a smile and open body language. Plus, he plans to practice pediatrics, so adjusting for speaking to a child is important. Under pressure, “I forgot about that,” he acknowledges to Pardy.

And he had to punt on some of the medical vocabulary. “You missed the ultrasound,” she tells him after another practice exercise. “Yeah, I had no clue how to say that one,” Giglio says.

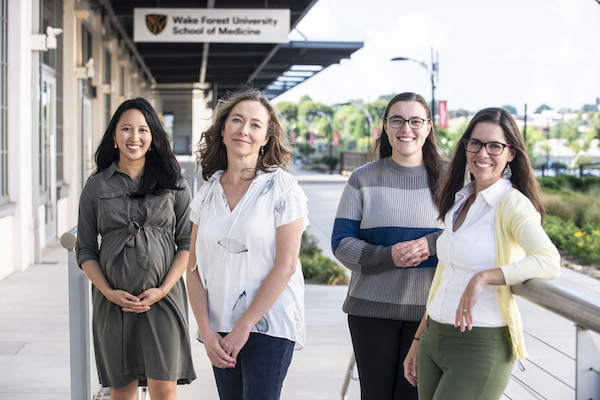

From left, Dr. Tiffany Shin, Mariana Pardy, Melisa Diadem Yuce (‘19, MD ‘23) and Carmen Pérez-Muñoz

She advises him to study the Spanish for all of the medical terms in his pulmonary/respiratory and cardiac modules, which the MAESTRO curriculum parallels.

Just as important as the language, Pardy tells Giglio, is how he makes a patient feel. He must maintain eye contact and be aware of his expressions. He is a caring person, and he must show it. He must convey warmth. That will help him gain the patient’s trust, she tells him. He will need that relationship with Spanish speakers, particularly those who come from remote cultures, lack immigration documents or have little faith in American institutions.

It is these last points — how do the patients feel, and do they trust you? — that serve as a valuable lesson for any medical student, the program founders say. After all, medical students already have an abundance of smarts, work ethic and ambition, or they wouldn’t have made it to medical school in the first place. Empathy matters, the professors say.

A UNICORN PROGRAM

The MAESTRO program emerged from the passions of its director, Dr. Tiffany Shin, and its associate director, Carmen Pérez-Muñoz.

Shin is a pediatrician and assistant professor in the medical school, fluent in Spanish and an advocate for improving care for the Hispanic community. Pérez-Muñoz is an assistant teaching professor of Spanish and a native of Spain. In 2019, she won a Teaching Innovation Award from the Wake Forest Center for the Advancement of Teaching for redesigning the Spanish for Health Professionals undergraduate class.

Shin is Chinese-American, with a Chinese- American father and a mother who is a native of Hong Kong and taught her Cantonese at home. Inspired by her parents’ lifelong commitment to service, Shin was interested from a young age in helping those suffering from illness, poverty or injustice. At Covenant College in Georgia she majored in biology with minors in chemistry and Spanish. She studied abroad in Costa Rica, focusing on Indigenous and marginalized people in Central America. In medical school at UNC-Chapel Hill, she took part in a four-year medical Spanish program. When she came to Wake Forest, she found students eager to better serve the many Hispanic patients in the community.

Besides studying and teaching Spanish, Pérez-Muñoz had worked in medical schools, beginning at UNC-Chapel Hill, where she earned her master’s degree and doctorate in Hispanic literature, and later at a private medical school in Missouri.

After coming to Wake Forest in 2016 to teach undergraduate Spanish, “I wanted to do something with the Wake School of Medicine, but I did not exactly know how to approach it,” she says. A mentor at UNC who knew Shin from her days in the medical Spanish program there connected the two women at Wake Forest.

“We hit it off immediately, both at a personal and at a professional level,” Pérez-Muñoz says. “She had the same idea. We combined our strengths, and with her contacts at the med school, … literally six months after we met, we were launching the pilot. … This happened very fast.”

This model that Dr. Shin and Dr. Pérez-Muñoz have is unique and particularly useful in that they balance each other in terms of their fields of expertise and their prior training.

Pérez-Muñoz says she and Shin, before recruiting Pardy, led the program as “a two-woman show,” taking only 10 to 12 students a year despite many more applications. The program is unusual in merging language pedagogy from Pérez-Muñoz with medical education principles from Shin.

“There’s not a program like this anywhere in the country that we’ve heard of,” says Shin, who is on the steering committee of the National Association of Medical Spanish (NAMS). “And the people who run programs at other universities have commented that, ‘Wow, I wish I could have that at my institution. You guys are a unicorn together.’”

Dr. Pilar Ortega, president of NAMS, is familiar with Wake Forest’s program. She is a clinical associate professor in the departments of medical education and emergency medicine at the University of Illinois at Chicago.

She says results of a survey published in 2021 found that nearly 80% of the 125 medical schools that responded offered some form of medical Spanish program, but students, rather than faculty, run about half of them. She says that was the norm until a decade ago. Having at least one faculty member dedicated to a program is seen as important to incorporating clinical knowledge into the curriculum, Ortega says.

“This model that Dr. Shin and Dr. Pérez-Muñoz have is unique and particularly useful in that they balance each other in terms of their fields of expertise and their prior training,” Ortega says.

A program like Wake Forest’s trains doctors in ways that benefit patients and also can attract more Hispanic students to become doctors and bring improved care to Hispanic communities, Ortega says.

BARRIERS AND DANGERS

Shin, Pérez-Muñoz and Pardy, a project manager in community-engaged research studies in the Department of Social Sciences at Wake Forest’s medical school, know the stakes are high for Spanish-speaking patients. The medical system can bewilder even native-born Americans.

Consider an alarmingly simple scenario: “Take these pills once daily,” a doctor tells a patient from rural Mexico. Without fully understanding, the patient does the polite thing and nods in agreement. The pharmacy label on the bottle will reinforce the message. “Take once a day.”

Dr. Tiffany Shin

But the Spanish word for 11 is “once.” While it’s pronounced “ON-say,” the potential for overdose is clear if the label isn’t in Spanish and the patient hasn’t received careful instruction from the doctor or an interpreter.

Culture, too, can complicate the care of Spanish-only speakers. Some patients might not realize that their herbal remedies or methods from a community healer are relevant to the doctor. A physician who asks questions in a way that feels too direct, too private or too judgmental might not get accurate answers. And patients from other cultures who lack trust in the doctor might feel free to adjust their treatment themselves if they don’t like side effects or don’t see results.

Cultural humility is a key element of the program, Pérez-Muñoz says. What a doctor might say to an Anglo speaker is not necessarily the way to approach a Spanish speaker, she says.

An example is the “pain scale” used by American doctors. Gauging pain on a numerical scale from 1 to 10 is not a natural concept in many Hispanic cultures, the professors say.

Chronic pain can register differently than an acute spasm. Pain varies over time. And a woman who has given birth or someone who has passed a kidney stone has a different pain spectrum than a person blessed with a history of only minor pains.

The program teaches students to use alternatives, asking how the pain affects patients’ lives or limits activities, such as sleeping, walking or working. “It’s a practice that is becoming more common for everybody,” Pérez-Muñoz says.

CONNECTING CAMPUSES

For medical student Melisa Diadem Yuce (’19, MD ’23), taking the undergraduate medical Spanish class with Pérez-Muñoz gave her a leg up in pursuing her dream of becoming a doctor. The class also can steer undergraduates into other medical careers, including interpreting or translating.

The class requires students to do community service such as volunteering in clinics, do research projects on Hispanic health issues and learn to do medical interviews. It includes a final roleplay assignment in a mock exam room at the medical school with a native Spanish speaker. Each student has 20 minutes to conduct a full medical history — an exercise that the medical students in MAESTRO also tackle, with savvy interpreters acting as patients and throwing curveballs to test students’ ability to pivot.

Yuce has traveled the full circle of medical Spanish at Wake Forest. In her fourth year of medical school, she is the current co-chair of the student design committee that has helped shape the MAESTRO curriculum and support students.

Like Shin, Yuce is multicultural and has known since childhood that she wanted to become a doctor, the first in her family. Her parents immigrated from Turkey to Greensboro, North Carolina. They were both music teachers and instilled service as a value, and Yuce was bilingual because they both spoke Turkish at home.

“I was really interested in anatomy. I also really enjoyed science. I enjoyed solving problems. I really liked doing puzzles when I was little, like logic puzzles,” Yuce says. “Serving people was also very important for me. So, I felt like (medicine) was a good intersection of all the things that I enjoyed.”

She learned Spanish in elementary and high school and saw it as a way to indulge her fascination with cultures and to meet people. She majored in Spanish at Wake Forest, with a concentration in Spanish for the medical profession. She minored in chemistry on the pre-med track and added a minor in Chinese language and culture. A heavy agenda didn’t slow her down; she graduated summa cum laude.

She has kept up the pace in medical school, with plans to specialize in OB/GYN. On the MAESTRO student design team, she not only gives feedback on the curriculum but also recruits participants and offers input during applicant selection.

Yuce says her undergraduate class with Pérez-Muñoz gave her a head start. The first year of MAESTRO formed a solid language base and helped her develop her linguistic style and adjust to the patient’s level. “Sometimes you can’t go using all the fancy words that you learned. You need to find ways to explain things to people based on their health literacy,” Yuce says. She has accepted the extra work of designing MAESTRO as part of her passion.

Shin says, “The students have given input from Day One. … They provide great insight into how can we improve this. … They’re full-time learners; that’s their job. They know best how they learn best. And they come up with really creative and innovative ideas.”

For example, Shin says, students adapted a flashcard app called Anki for studying medical content. They suggested the best times for certain assessments that might clash with days scheduled for eight hours of lectures.

From left, Mariana Pardy, Carmen Pérez-Muñoz, Melisa Diadem Yuce (‘19, MD ‘23) and Dr. Tiffany Shin

A GULP FROM THE FIRE HOSE

In August, first-year MAESTRO students arrive at a medical school classroom for the introductory class with Shin, Pérez-Muñoz and Pardy.

Melisa Diadem Yuce (’19, MD ’23)

The students will go through monthly workshops with the instructors, learn to take medical histories and perform a required 50 hours of community service in clinics by their third year. The second year brings faculty-guided instruction and self-study, with students watching videos of actors playing patients and recording their own responses for faculty to review. Students also prepare for a major goal, passing the exam that certifies them to work with Spanish-speaking patients without a medical interpreter. The third year focuses on clinical rotations, and the fourth year on community engagement.

The program doesn’t have an official estimate of student hours spent in MAESTRO, but Yuce, midway through her fourth year, has logged 105 volunteer hours as an interpreter. She estimates she spent about 40 hours on workshops and practice sessions in the first two years. The last two years are more informal, using Spanish in clinical settings.

Shin says the often-used analogy is that the pace of medical school is like drinking out of a fire hose. “And then our students sought to do more — in another language, which is tiring,” she says.

The dozen students from across the country share their backgrounds: this class has a handful of students who grew up speaking Spanish at home, in Cuba, Peru, Mexico. All students speak a high level of Spanish, a prerequisite for admission, though one young man jokes that he has spoken mostly “party Spanish.”

Language proficiency is important in choosing participants, say Pérez-Muñoz and Shin, but most critical is a passion for working with Hispanic patients and a strong sense of empathy.

Doctors, in a fast-paced environment, are dealing with patients who might be in a very fragile state and “not even knowing if people are going to truly understand what they’re going through,” Pérez-Muñoz says. “It is extra important that they feel like somebody cares about them.”

SPANISH UNDER SCRUTINY

In their first MAESTRO class in August, both Spanish and English are spoken, but most of the program will happen in Spanish. The teachers pass out slips of paper with various scenarios describing a patient and symptoms. In pairs, the students take turns doing a medical interview of the other student posing as the patient, with instructions to reveal some information only if asked. The professors hover, and some students get visibly flustered when an instructor stands close to watch and listen.

Afterward, the instructors give feedback to the class. “You don’t have to say gracias after every sentence,” Pérez-Muñoz tells them, the first of many lessons in maintaining a balance between formality and friendliness. “This is a medical environment. They are here to get your help. They expect questions.”

Sensitivity is key. Food scarcity can affect a patient’s health, but asking parents whether they regularly run out of food at home can feel insulting or paternalistic, the students learn. The doctor can smooth the way by explaining that all patients get asked these same personal questions. The doctor also can work more indirectly, noting that the pandemic or rising grocery prices have stressed many families’ finances and asking if that has affected the patient’s family.

“By normalizing it, you are opening that window for people to be a little bit more likely to share whatever issues they might be having,” Pérez-Muñoz says.

The medical students will get hundreds of such lessons in the next four years as they learn to be doctors.

Many of the heritage Spanish speakers in the current class talked in their application essays about having to help parents or grandparents who could not speak English and needed medical care in a small town with no interpreting services, Pérez-Muñoz says.

“It gives them that perspective of ‘It’s not easy for these people. I want to be one of the doctors that can help them.’”