Come along for a tour of Wake Forest to see bits of history scattered across campus.

Pause for a moment to look closely under the branches of dogwoods and oak trees around Wait Chapel and beneath the magnolias on Manchester Plaza. Wander through Benson University Center. Stop to smell the roses at Byrum Welcome Center. You might be surprised. Tucked away, sometimes forgotten, under trees, down lonely corridors, in staircases, and yes, in a rose garden, are plaques commemorating students, alumni and professors.

Look down to notice the brick pavers in Tribble Hall’s courtyard and outside Farrell Hall. Other tributes are right in front of us. Benches around Hearn Plaza have plaques heralding students and alumni who should be remembered. Plaques adorn classroom and office doors in academic buildings and special spaces in Scales Fine Arts Center and Reynolds Gym. You’ve probably walked right by without giving them a second thought. Take a minute to look, and you might be inspired.

Each small plaque offers a glimpse into Wake Forest’s past and the Wake Foresters who have come before us. But the plaques give only the barest of details. Behind each plaque is a person or story worth contemplating. Each has a history, contributing to Wake Forest’s unfolding story. Here are a few of our favorites.

Jump to:

- A Fire to Be Kindled

- An Artful Legacy

- Indigenous Lands

- Campus Wonder Dogs

- Be a Rainbow

- Remembering Lives Lost

- The Least of These

- Honoring Professors

- The “Divine Nine”

- The Flying Parson

- ‘Welcome to Wake Forest’

- The Provocative Editor

- Grace’s Garden

- For There is Hope for a Tree

- The Age of Dinosaurs

- The Comic Professor

- The Family She Loved

- Honoring Traditions

- A Soothing Tribute

A Fire to Be Kindled

Farrell Hall opened in 2013 as the new home for the School of Business, bringing graduate and undergraduate business programs together under one roof. The late Mike Farrell (LL.D. ’13) and his wife, Mary Flynn Farrell, parents of Michael Edward Farrell (’10), gave $10 million toward construction of the building, named for Mike Farrell’s late father, Michael John Farrell.

Outside the $55 million building, on the Reynolds American Foundation Terrace, a fire pit surrounded by rocking chairs offers a quiet, peaceful spot for studying, contemplation or relaxation beneath a canopy of trees. Made possible by a gift from John Doscas (P ’14), the fire pit offers an engraved, inspiring message to all who study at Wake Forest:

“The mind is not a vessel to be

filled, but a fire to be kindled”

– Plutarch

An Artful Legacy

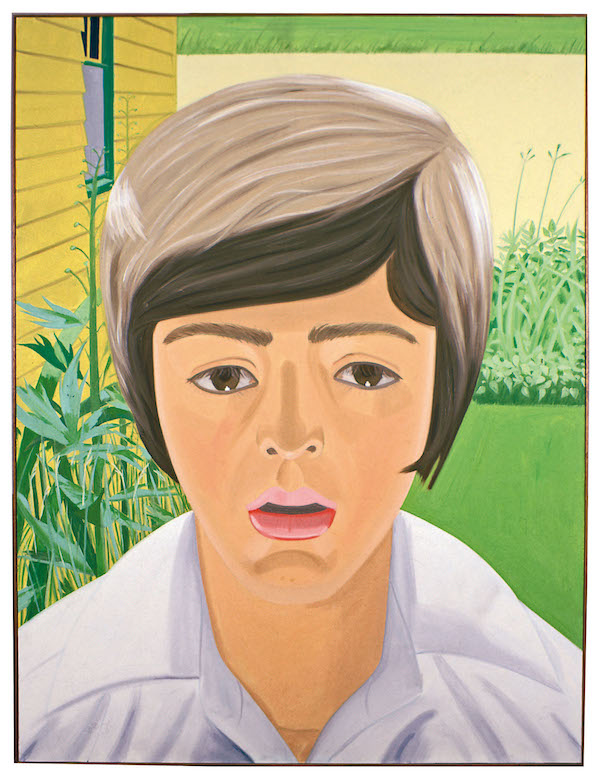

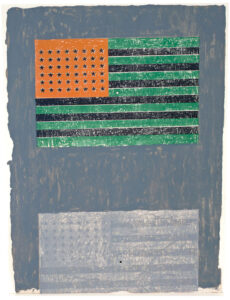

Look for the legacy of Mark Reece around campus in the paintings, prints, sculpture and photography in what was known for many years as the Student Union Collection of Contemporary Art. Benson University Center houses many of the pieces. Its fourth-floor gallery space is named for Reece (’49, P ’77, ’81, ’85), the longtime dean of men and Student Union adviser and later dean of students.

“Vincent with Open Mouth” 1970, Alex Katz, acquired in 1973; © 2023 Alex Katz / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

“Flags” 1967-68, Jasper Johns, acquired in 1969; © 2023 Jasper Johns / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Reece had the bold idea in 1963 — before Wake Forest even had an art department — to give students money to travel to New York to buy contemporary art for Wake Forest. Back in 1969, he offered his modest hope for the collection: “I believe that the end result, not many years from now, will be a collection of some significance of which we can all be proud.”

He was right. Every four years (with the exception of the pandemic year when students selected works via Zoom), students have visited New York art galleries and debated which artwork to add to the collection. The collection has grown to 160 pieces by more than 100 artists, including Pablo Picasso, Jasper Johns, Roy Lichtenstein, Alex Katz and Louise Nevelson.

Last year, John Reece (’81, P ’07, ’09) and Libby Reece (P ’07, ’09) endowed a conservation fund to steward the work and to bestow a new name: the Mark H. Reece Collection of Student-Acquired Contemporary Art. This fall, Wake Forest will celebrate the 60th anniversary of its one-of-a-kind art-buying trip.

Back to Top

Indigenous Lands

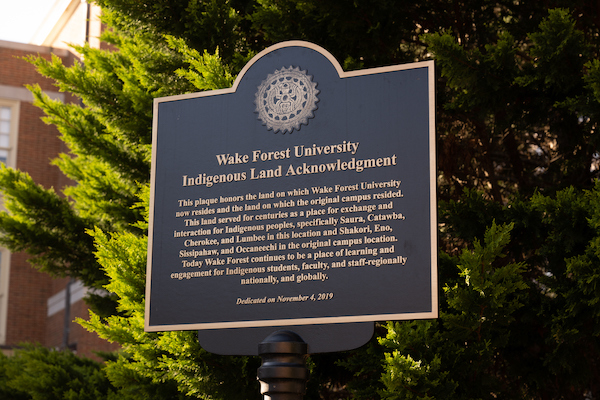

Representatives from the North Carolina tribal nations were on hand in 2019 when Wake Forest unveiled a plaque in the Tribble Hall courtyard honoring the land on which the University and the original campus were built.

Savannah Baber (’19), a citizen of the Lumbee Tribe of North Carolina and the Chickahominy Tribe of Virginia, spoke of Wake Forest’s indigenous legacy “from the ancestors of the Catawba and other Native nations” to Jim Jones (’55, MD ’59), Wake Forest’s first Native American graduate, to today’s Native American students.

“I was fortunate to be surrounded by faculty and staff mentors as well as supportive peers who constantly encouraged me to advocate for and highlight Native culture through my studies and activities on campus, but … not all Native students are so lucky,” Baber said at the dedication. “Native students need to know that they are seen and cared for by their institutions of higher education, and acknowledging the history of the land on which universities sit is a fantastic first step in letting indigenous students know that they are valued.”

Campus Wonder Dogs

A succession of golden retrievers has watched the passing parade of students from beneath a magnolia tree on Manchester Plaza. If you don’t believe that, ask the latest golden retriever that kept watch, Glacier, once described as “the campus wonder dog.”

“The lower quad is mine; that’s my turf,” Glacier barked to the Old Gold & Black some years back. “Everyone says ‘hi’ to me when they see me. Campus is sort of like ‘Cheers’ for me; everybody knows my name.”

Before Glacier there was Montana (aka Tana), who started coming to campus in the 1990s with her “dog parent,” now retired Professor of Communication and Director of Debate Allan Louden. After Montana’s death in 2002, a couple of students gave Louden a puppy, which he named Wyoming (aka Ms. Ming). Then came Glacier, adopted from the Forsyth County Humane Society in 2014.

Al Louden with Glacier

Each dog’s name reveals a bit of Louden’s past. Louden grew up in northwest Montana not far from Glacier National Park and graduated from Montana State University and the University of Montana. He taught at a community college in Wyoming before coming to Wake Forest in 1977 as a speech instructor and debate coach. He built an illustrious debate program that won national titles in 1997 and 2008 and consistently ranks among the top 10 in the country. (The team made history this year, winning the “Triple Crown” of national debates.)

All three golden retrievers dutifully accompanied Louden to meetings in Reynolda and classes in Carswell Hall. A student once wrote of Glacier, “All semester long, Glacier was a model student. He achieved perfect attendance, greeted every student with a friendly tail wag and quietly enjoyed the lecture, but mostly getting petted by the students.” Glacier could also be spotted walking in the annual “Hit the Bricks” event for the Brian Piccolo Cancer Research Fund.

Through the years, the friendly pups have invited many a student to pause from a busy day and strike up a conversation with Louden that might not have happened otherwise. “I’ve made some wonderful friendships,” Louden said.

A plaque, under a magnolia tree in front of Carswell Hall, honors Louden and his pups:

Marking This Spot

by sweet pups Montana, Wyoming, Glacier,

and indeed all the dogs of Wake Forest

Dedicated to Dr. Allan Louden

Professor, Director of Debate, Department Chair, Leader, Friend, and Dog Parent

To commemorate his retirement from the Department of

Communication on this 7th day of May 2022

Be A Rainbow

Asaying from the late Maya Angelou (L.H.D. ’77), Reynolds Professor of American Studies, calls out to us from a bench in front of Manchester Hall:

“Be a rainbow in someone else’s cloud.” In loving memory of

William Cary Nelson, Class of 1961, A Deacon Forever.

The plaque also includes a rainbow between two clouds. Nelson, who died in 2019, was a scientist and researcher with the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency in Research Triangle Park and lived in Chapel Hill, North Carolina. His family donated the bench.

“Wake Forest meant a lot to him; it’s where he met my mom (Susan Powers Nelson ’63),” said his daughter Lara Nelson Hanson (’93, P ’24, ’25). “He was a great listener and always made you feel good and happy. Maya Angelou was a professor when my husband (Stillman Hanson ’94, P ’24, ’25) and I were at Wake Forest, and this quote captured (my dad’s) essence. We wanted to honor him and hope this inspires others to be kind.”

Back to Top

Remembering Lives Lost

The Wake Forest community despaired in September 1996 when two members of Chi Omega sorority, 19-year-old sophomores Julie Hansen of Rockville, Maryland, and Maia Witzl of Arlington, Texas, died in a car accident on Polo Road. A car driven by an impaired driver struck the students’ car, just two blocks from campus.

Though the impaired driver went to prison, the case galvanized students to channel their grief to push for, and win, tougher North Carolina laws mandating sentences for habitual impaired offenders.

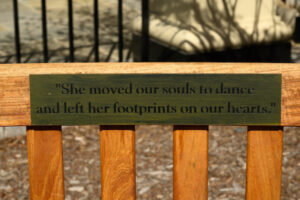

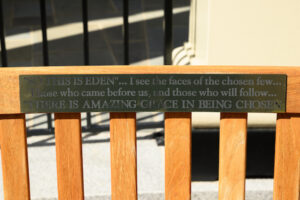

Three benches around Wait Chapel remember Hansen and Witzl. One bench has a plaque with both students’ names and their dates of birth and death. Two other benches remember each individually:

Julie Marie Hansen: She moved our souls to dance and left her footprints on our hearts.

Maia Cory Witzl: So this is Eden … I see the faces of the chosen few. Those who came before us, and those who will follow … There is amazing grace in being chosen.

Hansen, who wanted to become a doctor, was a track-and-field star in high school who volunteered with Students Against Drunk Driving. “I realize I’ve been given many gifts,” she wrote in her admissions essay. “I pray to God I know how to use them.”

Witzl, who wanted to become a lawyer, wrote in her admissions essay that she hoped “to be remembered as someone who has been an influence on people’s hearts. Although I’m far from perfect, I believe it’s possible to be a positive influence on others by word and by action.”

Two other students were killed that year. Sophomore Graham Gould died in a car accident in his hometown of Sanford, North Carolina. Senior Matt Alexander of Florence, South Carolina, died in the crash of TWA Flight 800 off Long Island, New York, on his way to a study-abroad program in Dijon, France.

At Commencement, then-President Thomas K. Hearn Jr. (L.H.D. ’04) remembered the four students and several other members of the University community lost that year. “(We) must leave here bearing lives, not just our own, whose promises, aspirations and ambitions must become ours, lives which live on in us and through us,” Hearn said. “Our families, our friends, our faculty mentors, and, yes, those lost to this life, all become part of us. This is what it means to live, as your diploma says, ‘For humanity.’ You are not one. You are many.”

Chi Omega places flowers on the benches every Sept. 4. The Chi Omega Foundation endowed scholarships in memory of Hansen and Witzl that are awarded to Wake Forest Chi Omega members each year.

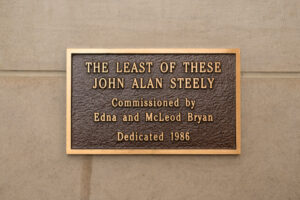

The Least of These

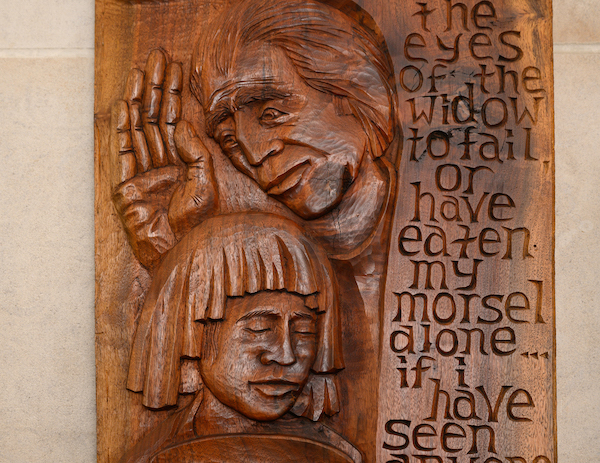

A tall wood carving in the foyer of Wait Chapel, “The Least of These,” uses selections from Job 31:13-32 and imagery to evoke service to humanity:

if i have withheld anything that the poor desired,

or have caused the eyes of the

widow to fail,

or have eaten my morsel alone …

if i have seen anyone perish for

lack of clothing,

or a poor man without covering…

if i have raised my hand against

the fatherless…

Job 31

A plaque notes that the sculpture was commissioned by Edna and McLeod Bryan (P ’71, ’72, ’75, ’82) and dedicated in 1986. The sculptor was the Bryans’ friend John Alan Steely, an artist who grew up in Wake Forest, North Carolina. He carved the piece from wood that “Mac” Bryan saved from a black walnut tree on his

family farm.

Professor Emeritus of Religion Bryan (’41, MA ’44) taught Christian ethics at Wake Forest from 1956 until 1987 and was an unflinching advocate for civil rights, social justice and environmental causes. He fought for the integration of Wake Forest in the 1960s and against the war in Vietnam, among other causes. Provost Emeritus Edwin G. Wilson (’43, P ’91, ’93) once described him as “Wake Forest’s acknowledged spokesman for the liberal causes of his lifetime. … Whenever there was a cause he believed in, his voice could be heard … against every manifestation of intolerance or injustice or unfairness.”

The Bryans wanted to provide a special work of art to display in Wait Chapel. They chose the theme of the piece, Mac Bryan once said, “not only because it (Wait Chapel) is a sanctuary and a place of worship, but also because in this place a variety of programs are held in tribute to ethical moments in human service, including programs of sponsorship of interracial activities, musical performances dedicated to peace, and pivotal meetings celebrating moments of historical importance.”

Back to Top

Honoring Professors

Stroll through the sunlit atrium that connects the Z. Smith Reynolds Library (named for the youngest son of R.J. and Katharine Reynolds) and the Edwin G. Wilson Wing (named for Provost Emeritus Edwin G. Wilson ’43, P ’91, ’93).

Bookcases in the atrium have simple brass plaques given in honor of past professors, administrators and alumni. The plaques are small, but the legacies of the individuals honored loom large, including:

·Ruth and Thomas Mullen (P ’85, ’88), given by Professor of English Elizabeth Phillips. Tom Mullen was Dean of the College, 1968-1995, and professor of history, 1957-2000.

·David and Renate Evans (P ’97) given by Sean Forsyth (’81). David Evans was professor of anthropology, 1966-2001, and founder and director of the Overseas Research Center.

·Maya Angelou (L.H.D. ’77) given by Eva Rodtwitt, lecturer in Romance languages. Angelou was Reynolds Professor of American Studies, 1982-2014.

·Merrill Berthrong given by friends and colleagues. Berthrong was director of libraries and associate professor of history, 1964-1989.

·Henry Stroupe (’35, MA ’37, P ’66, ’68) given by Professor of History Richard Barnett (’54, P ’81) and Betty Tribble Barnett (’55, P ’81). Stroupe was the first dean of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, 1967-1984, and professor of history, 1937-1984.

·Carlton West given by Vice President and Treasurer John G. Williard. West was College librarian, 1946-1975, and professor of history, 1928-1975.

The “Divine Nine”

Dedicated in 2010, the National Pan-Hellenic Council Garden on Manchester Plaza, near Benson University Center, pays tribute to nine historically African American fraternities and sororities and their impact on Wake Forest and the larger community.

Nine brick and granite podiums with plaques — one for each of the fraternities and sororities that make up the National Pan-Hellenic Council (NPHC) — are arranged on a circular brick and flagstone patio around a larger podium with a plaque describing the history of the NPHC.

The NPHC organizations emerged at a time of racial segregation and discrimination throughout the country. In 2020 to mark the council’s 90th anniversary, council president Vanetta Cheeks-Reeder said the organizations arose from the need to foster change in communities.  “From our advocacy to improve the health of Black & Brown lives to preparing our next generation of professionals for the workforce, the NPHC has and will remain relevant in this country,” she said in a statement from council headquarters in Decatur, Georgia.

“From our advocacy to improve the health of Black & Brown lives to preparing our next generation of professionals for the workforce, the NPHC has and will remain relevant in this country,” she said in a statement from council headquarters in Decatur, Georgia.

Five of the organizations — Alpha Phi Alpha fraternity, Alpha Kappa Alpha sorority, Kappa Alpha Psi fraternity, Omega Psi Phi fraternity and Delta Sigma Theta sorority — are active at Wake Forest. Phi Beta Sigma fraternity has been active at Wake Forest in the past.

Back to Top

The Flying Parson

Between the Wright brothers and Charles Lindbergh, there was Belvin W. Maynard, a Wake Forest ministerial student who became known in 1919 as the “Flying Parson” and the greatest pilot on earth. As a large

brass plaque, largely forgotten in a Wait Chapel staircase, notes, Maynard was a “pioneer in conquest of the air” and a “distinguished soldier in World War. … World famous but modest, brave but gentle, honored above others, his thought was always of others.”

Maynard grew up on a farm in North Carolina and was an expert mechanic who could take a car apart and rebuild it. He enrolled at Wake Forest in 1913 to become a minister but left to join the U.S. Army Air Service during World War I. He proved to be a skilled aviator and became one of the top American test pilots in France.

After the war ended, he remained in the Air Service but used his skills to promote flying. He set a world record by performing 318 consecutive loops in 67 minutes in a Sopwith Camel at a French airfield, and, in 1919, he won the International Aerial Derby, flying from New York to Toronto and back.

That same year, Maynard won the longest air race of its day, a transcontinental race from New York to San Francisco and back in a de Havilland DH-4 biplane he named “Hello Frisco.” Mechanic William Kline shared the rear cockpit seat with Maynard’s German shepherd puppy, Trixie, brought from France after the war. While other pilots relied on roads and rivers to navigate, Maynard used a compass and pushed his plane to fly faster than other pilots did.

That same year, Maynard won the longest air race of its day, a transcontinental race from New York to San Francisco and back in a de Havilland DH-4 biplane he named “Hello Frisco.” Mechanic William Kline shared the rear cockpit seat with Maynard’s German shepherd puppy, Trixie, brought from France after the war. While other pilots relied on roads and rivers to navigate, Maynard used a compass and pushed his plane to fly faster than other pilots did.

Spectators turned out to cheer him at stops along the way. “Parson, the sinners are with you,” one spectator told him. “He may be a parson, but he certainly flies like the devil,” another said. Flying through rain, snow, winds and fog, Maynard was the first pilot to land at Presidio Field in San Francisco after more than 25 hours in the air, spread over three days. “No human being had ever made a faster journey across the continent,” wrote John Lancaster in his book, “The Great Air Race: Glory, Tragedy, and the Dawn of American Aviation.”

On the return flight, even with an unscheduled stop when he was forced to land in a Nebraska cornfield because of engine trouble, Maynard beat the other competitors to New York, becoming the first person to fly from the Atlantic to the Pacific and back.

Maynard became the best-known airman in the country, and Winston-Salem named its commercial airfield, the first in the state, in his honor. He delighted crowds at the dedication by performing aerial stunts before landing. (Maynard Field operated until Miller Municipal Air Field — the forerunner to Smith Reynolds Airport — opened in the 1930s.)

Belvin Maynard with his dog, Trixie, and mechanic William Kline

On a victory tour of North Carolina, Maynard was joined by a newspaper reporter for a flight above Fayetteville. “To make the flight with Lieutenant Belvin Maynard, whom The New York Times described as ‘the most celebrated aviator on earth,’ is too thrilling for words,” she wrote. “(T)he Flying Parson is not only a king among aviators, but a prince of a gentleman.”

But Maynard’s star quickly faded. After he accused some of his competitors in the transcontinental race of being drunk, the Army threatened to court-martial him. He left the Air Service but continued flying. In 1922, he died when his plane crashed while he was performing stunts at a fair in Vermont. He was 29.

The Flying Parson’s story came full circle when his brother’s son, Doug Maynard (’55, MD ’59, P ’88), enrolled at Wake Forest. Maynard was born a dozen years after his famous uncle died. “I would like to have known him,” said Maynard, the retired chair of radiology at what is today Atrium Health Wake Forest Baptist Medical Center. “He must have been quite a character.”

Back to Top

‘Welcome to Wake Forest’

Almost everyone who attended Wake Forest from the 1960s through the early 2000s can thank William G. Starling (’57), who carefully, and lovingly, crafted the student body year after year. Starling joined the admissions office a few years after graduating and was named director of admissions in 1964 and dean of admissions and financial aid in 2001, shortly before he died.

Across four decades of interviewing untold thousands of potential students and reading thousands of essays, he never lost his sense of purpose. With integrity, warmth, kindness, curiosity and a sense of humor, he never forgot that behind each application was a unique young person full of hopes and dreams. With an unerring feel for whether students would be a good fit and an uncanny sense for their potential, he was the sustainer of Wake Forest’s future. He welcomed generations of students to join him on the campus he loved and never left.

Starling was 65 when he died, still young at heart and full of hope for future classes of students. Four months after his death, Wake Forest renamed the admissions building William G. Starling Hall. After the admissions office moved next door to Porter Byrum Welcome Center in 2011, a bench near the new entrance commemorated the Wake Forest legend.

The Southern Consortium of colleges and universities donated the bench, but the words on its plaque could have been written by many of us:

Dedicated to the warm and lasting memory of our good friend and colleague, William G. Starling, 1935 – 2001.

Starling Hall remains home, appropriately, to the Program for Leadership and Character.

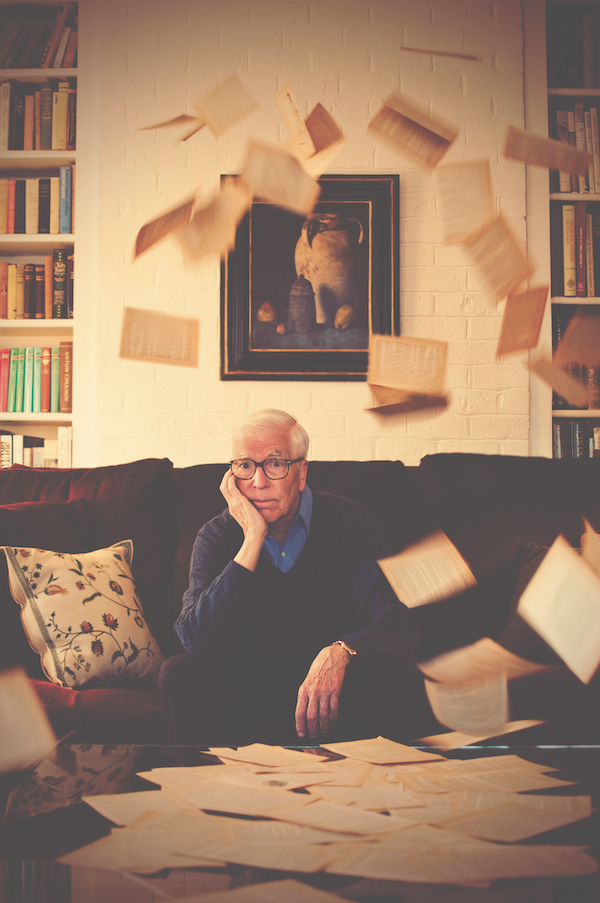

The Provocative Editor

As editor of The Student magazine in the late 1940s, editor Harold T.P. Hayes (’48, L.H.D. ’89, P ’79, ’91) brought strong writing, creative photography and original artwork to what had been a staid college publication. Hayes, who once referred to himself as a “solid C-average” student, left an indelible mark on Wake Forest’s — and the nation’s — literary scene.

“Under Harold’s editorship, we knew at once that something provocative and revolutionary had happened,” Provost Emeritus Edwin G. Wilson (’43, P ’91, ’93) once said of Hayes’ The Student magazine. “This new magazine had lightness and wit and spontaneity, but it also had an editorial control derived from exactingly professional literary and artistic standards.”

Hayes took that sense of style and creativity with him to New York, where he was editor of Esquire magazine during the turbulent 1960s and early 1970s. He ushered in the New Journalism literary style with smartly written, novel-like journalistic pieces by some of the country’s top writers, including Nora Ephron, Norman Mailer, Gay Talese, Gore Vidal and Tom Wolfe. Coupled with provocative covers — Andy Warhol drowning in a Campbell’s Soup can, Muhammad Ali as St. Sebastian and boxer Sonny Liston as a Black Santa Claus — Esquire became the literary and visual embodiment of the era.

Hayes’ son, Tom Hayes (’79), described Esquire as “the red-hot center of journalism … irreverent, brash, fearless … rich with attitude” in his 2014 documentary about his father, “Smiling Through the Apocalypse: Esquire in the 60s.” “What I learned most, … is how he would look at something and put a spin on it that would be so completely outside the box,” Tom Hayes said. “Anything obvious or conventional was boring and only became interesting if you looked past what everyone else was seeing and tilted it on a specific angle.”

When Benson University Center opened in 1990, the office of The Student magazine (now called Three to Four Ounces) was dedicated in memory of Hayes, who had died the year before. Many of his personal papers are in the Z. Smith Reynolds Library Special Collections & Archives, including original manuscripts, correspondence, drafts of articles and cover designs from his time at Esquire.

Back to Top

Grace’s Garden

The late Porter B. Byrum’s name is prominently displayed on Byrum Welcome Center, but look to small plaques on three benches for the people and places important to Byrum (JD ’42).

Byrum, an attorney, businessman and philanthropist from Charlotte, died in 2017. He was the most generous individual donor in Wake Forest history, giving more than $120 million to the University over the course of decades. His generosity has enabled hundreds of undergraduate and law students to attend Wake Forest.

“I know that I didn’t pay my way when I went to Wake Forest,” Byrum once said. He and three of his brothers received free tuition to Wake Forest because his father, John Thomas Byrum (1908), was a minister. “Given the circumstances, my daddy never would have been able to have gotten four boys through Wake Forest, so somebody ought to pay back the debt. And it makes me feel good to do that.”

Named for Byrum, the admissions and welcome center opened in 2011. In 2016, Wake Forest planted specially cultivated Wake Forest roses at its entrance to honor Grace Smith Thomas, Bryum’s longtime friend who loved roses. A plaque on a bench amid the rose bushes recognizes her:

Grace’s Garden, planted in honor of Grace Smith Thomas, special friend of Porter B. Byrum (JD ’42) and Wake Forest University.

A second bench nearby honors Byrum’s commitment to Wake Forest:

In Loving Memory of Porter B. Byrum (JD ’42), who always remembered the opportunities of his Wake Forest Education (1920-2017).

A third bench, behind Byrum Center, honors Byrum’s parents and his stepmother, Isa Ward Byrum. The plaque includes a quote that you can imagine Porter Byrum saying:

“Education is something the world can’t take away from you, and something you will enjoy every day of your life.”

For There is Hope for a Tree

When a heritage oak tree beside Worrell Professional Center was felled for construction of an addition to house the Department of Health and Exercise Science, the tree gained new life as a bench behind Wait Chapel. As the plaque notes:

“For there is hope for a tree” … Job 14:7. Made from an Oak Tree that stood by the Worrell Building. Crafted by the construction team at Facilities and Campus Services. Gifted to WFU by the School of Divinity Class of 2018.

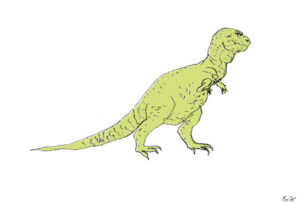

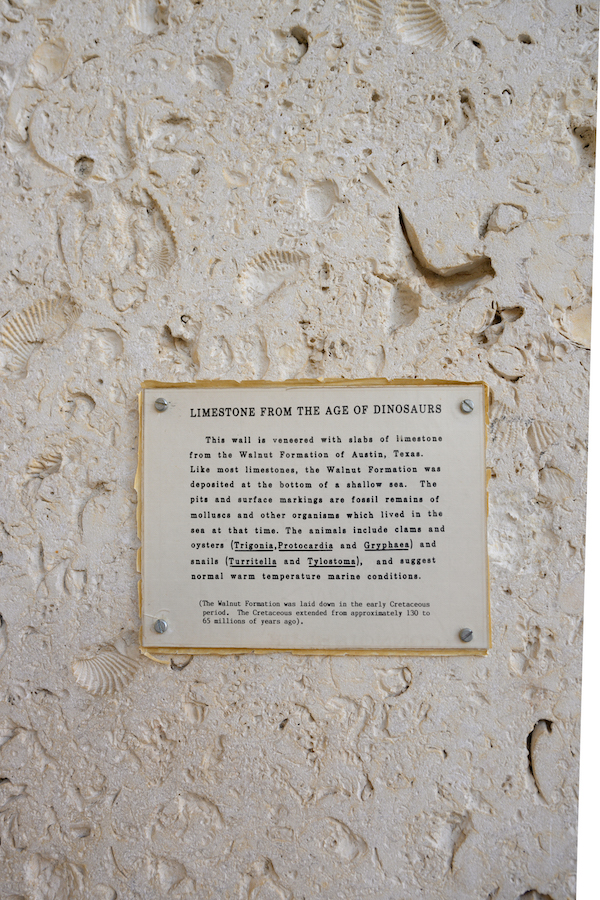

The Age of Dinosaurs

Examine the rough limestone walls in the two-story lobby of Winston Hall. Run your fingers over the walls, pockmarked with the fossil remains of clams, oysters, snails and other organisms that lived when dinosaurs roamed the earth.

As a plaque explains:

This wall is veneered with slabs of limestone from the Walnut Formation of Austin, Texas. Like most limestones, the Walnut Formation was deposited at the bottom of a shallow sea. The pits and surface markings are fossil remains of molluscs and other organisms which lived in the sea at that time. … (The Walnut Formation was laid down in the early Cretaceous period. … approximately 130 to 65 millions of years ago.)

Longtime biology professor Charlie Allen (’39, MA ’41) had the idea for the unique feature when he helped design what was originally known as the Life Sciences Building for the biology and psychology departments. (The building houses only biology today.) It cost $1.3 million, funded through donations from individuals, businesses and foundations in Forsyth County.

As a student, Allen studied evolution with biology professor and Wake Forest’s seventh president, William Louis Poteat (Class of 1877, MA 1889, P 1906). After graduating, Allen was an aerial reconnaissance photographer in the U.S. Army Air Forces during World War II; his photographs of wartime England and France are in the State Archives of North Carolina. After the war, he returned to Wake Forest and taught evolution and other subjects until retiring in 1989. In addition to designing Winston Hall, he also helped design Scales Fine Arts Center and started the Artist Series, now the Secrest Artists Series. Allen died in 2005.

At the dedication of Winston Hall in 1961, the Old Gold & Black reported, “One feature that attracted attention of visitors was the walls of the lobby. The walls are made of fossil sandstone from Texas, estimated to be about 180 million years old.”

The Comic Professor

For four decades, Professor Emeritus of History Jim Barefield reveled in teaching students the art of comedy. Much of his teaching genius unfolded in Tribble Hall A109 — with its comfy couches and armchairs — where he taught the cornerstone honors classes “The Ironic View” and “The Comic View.” His wry sense of humor, delivered in his inimitably raspy voice, and his infectious love of irony both in literature and in life endeared him to students.

Photo by Heather Evans Smith

Barefield’s influence extended far beyond Tribble Hall. He helped build Wake Forest’s overseas studies program, particularly at Casa Artom in Venice and Worrell House in London, and he was a valued mentor and adviser for undergraduate scholarship holders and for students competing for postgraduate scholarships, including the Rhodes and Fulbright. After he retired in 2004, he continued conducting interviews with prospective students for the undergraduate admissions office.

But his most lasting impact came as architect of the University’s pathbreaking interdisciplinary honors program. While he might find it wryly amusing that a classroom is named in his honor, his legion of devoted former students would surely find it unironic that his old classroom is named the Barefield Honors Seminar Room with not one, but two(!) plaques.

The Family She Loved

From 1986 until her death in 1997, Grace O’Neill — often dressed in formal black tie, vest and white shirt — stood at the Magnolia Room doors welcoming students, faculty and staff. She set the standard for the countless food service workers who followed her to become part of the Wake Forest family, providing meals and comfort, especially to students far from home.

After O’Neill’s death, then-Wake Forest President Thomas K. Hearn Jr. (L.H.D. ’04) remembered her in his graduation remarks, and the community planted a tree in her memory in front of Tribble Hall:

Dedicated to Grace A. O’Neill, Magnolia Room Manager,

1986 – 1997, from the Wake Forest family that she loved.

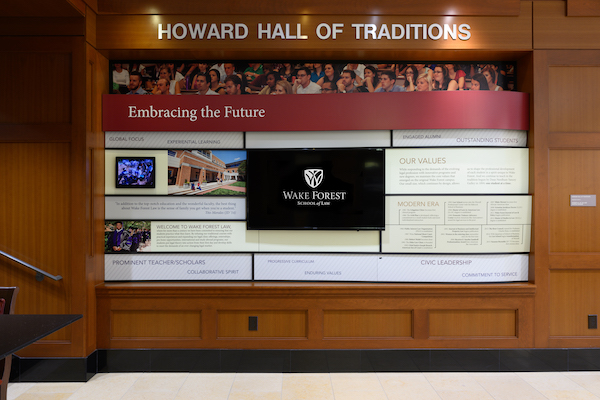

Honoring Traditions

The Howard Hall of Traditions, at the main entrance to Worrell Professional Center, was a gift from Ken Howard (JD ’82) and Martha Howard. The installation occurred in 2015 after a renovation for the School of Law and the move by the School of Business to Farrell Hall.

Text, photographs and videos share the law school’s story, beginning with its founding in 1894. Panels highlight the school’s values and the traits that define a Wake Forest lawyer: honesty, diligence, competence, creativity, thoughtfulness, dedication, passion and civility.

“Knowing the history of the school you attend can only make you appreciate what a special place that school is,” said Ken Howard, director of the North Carolina Museum of History and a past chair of the law school board of visitors.

Back to Top

A Soothing Tribute

A multiyear, $58 million renovation of Reynolds Gym, completed in 2018, transformed the historic building into the Wake Forest Wellbeing Center, tripling the amount of fitness space on campus and creating a hub for health and wellbeing.

While the building hosts loud weightlifters, Zumba dancers and splashing swimmers, it also has a place for fitness buffs to pause and reflect: a calming, two-story water wall. Dave Wahrhaftig (MBA ’82, P ’18, ’21) and Sue Wahrhaftig (P ’18, ’21) gave the wall in memory of Dave’s godson, John R. “Jack” Mann Jr., who died at age 24 in 2012. He is the son of John “Roy” Mann (MBA ’82, P ’20) and Sally Mann (P ’20).

Roy Mann and Dave Wahrhaftig have been friends since their student days in MBA school. Roy Mann is godfather to Dave and Sue’s oldest son, John Wahrhaftig (’18).

Dave Wahrhaftig helped lead the fundraising for the Reynolds Gym transformation, and Sue Wahrhaftig designed the water wall. They wanted to honor Jack Mann’s memory and their belief that mental health should be considered a fundamental component of wellbeing.

“Jack was a great kid and was such a positive influence on so many people,” said Sue Wahrhaftig. “We have friends and family who have been impacted by mental illness. The sound of water can be relaxing and soothing, and hopefully users of Reynolds Gym enjoy that. More importantly, perhaps Jack’s story can make a difference to others.”