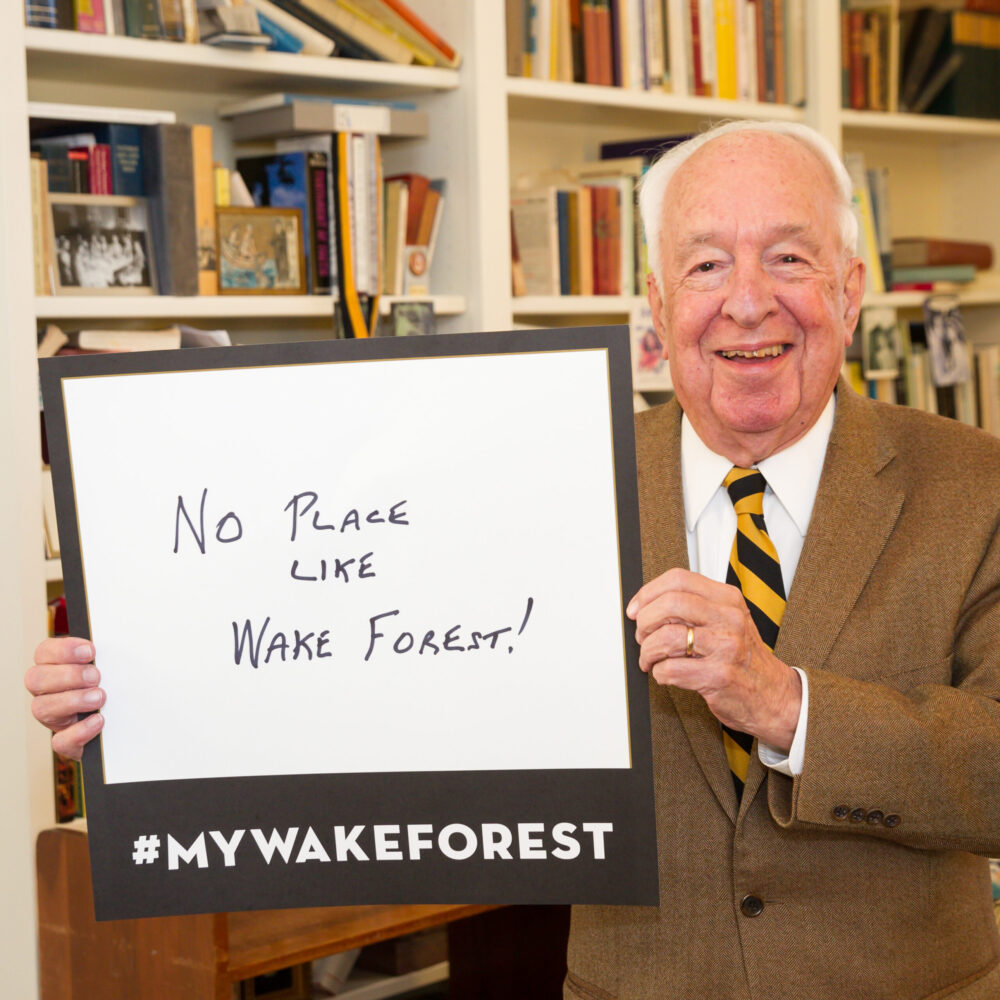

Editor’s note: We’re remembering, and will continue to honor, longtime retired Professor of English and Provost Emeritus Edwin G. Wilson, who passed away on March 13, 2024, at age 101. Wilson was beloved and revered for his inspired teaching and character. We were honored to run this wonderful conversation last fall between Wilson and Debbie Best, the first female Dean of the College and William L. Poteat Professor of Psychology. There’s more at the University’s remembrance website — where you can share memories and leave condolences.

In August 2022, Warren Anderson (’74) sat down for a conversation with two Wake Forest greats — Dr. Ed Wilson (’43, P ’91, ’93) and Dr. Debbie Best (’70, MA ’72). The occasion was Wilson’s upcoming 100th birthday last February and Best’s upcoming 51st and final year as a Wake Forest professor before her retirement last summer. The two candidly discussed their time at the University and their experience as students, professors and administrators.

Wilson, fondly known as “Mr. Wake Forest,” has spent his entire life at Wake Forest, except for several years in the U.S. Navy and graduate school at Harvard. In addition to teaching English, he was Dean of the College and the first Provost of the University. He received the Reinhardt Award for Distinguished Teaching and the 2004 Medallion of Merit, Wake Forest’s highest award for service. He is the author of “Songs of Wake Forest” and “The History of Wake Forest University, Volume 5, 1967-1983.”

Best came to Wake Forest as a student in 1966 and never left. She began teaching at Wake Forest in 1972 and later became the William L. Poteat Professor of Psychology. She served as psychology department chair and as the first woman Dean of the College. She won the Reid-Doyle Teaching Award, the first Excellence in Research Award and the Schoonmaker Award for Community Service.

Comments have been lightly edited. Special thanks to documentary film program graduate student Parker Beverly (’23), who filmed the interview.

The University Archives is collecting memories of Dr. Wilson from former students who took one of his memorable classes and others who have known him during his long association with Wake Forest. Share your memories in writing or in a video.

Ed Wilson and Debbie Best, August 2022

Warren Anderson: Both of you have taught at Wake Forest for many decades and have had thousands of students. What did you, as a teacher, want your students to take out into the world with them when they left college?

Ed Wilson: I had the advantage of teaching literature, mainly poetry. Most great poetry carries with it more than just the sound of the words. It carries with it the meaning of life. You can’t read Yeats or Wordsworth or Keats without absorbing what they saw in life. I want the students to be able to read the poems and understand them and maybe recite them. But at the same time, see what is underlying the poem.

When Wordsworth says: “Earth has not anything to show more fair; dull would he be of soul who could pass by a sight so touching in its majesty” then you understand that Wordsworth is looking at a bridge in London, which he will cross, and sees what it symbolizes about the city. Through that poem, the student learns the words, he learns what the bridge symbolizes. And he also sees what that bridge — or any bridge — might symbolize for him, the student, if he will look at it.

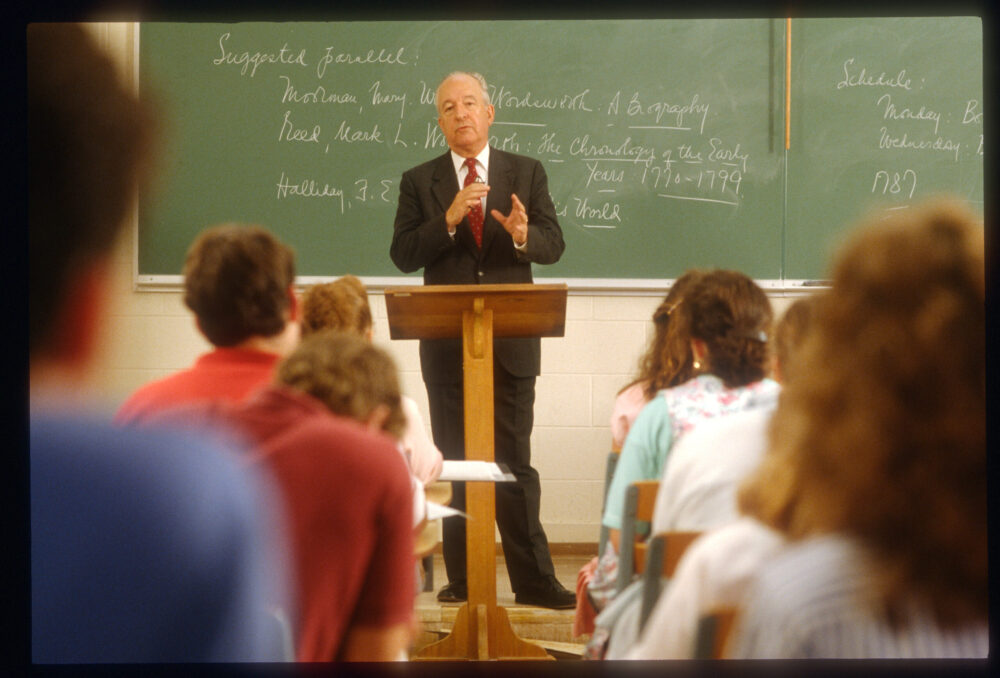

Ed Wilson teaches in Tribble Hall in 1989.

Warren Anderson: What does the student do with that?

Ed Wilson: Well, you hope that when the student lives life, he will look around and see more than just his surroundings. He will see what it means. He goes to church and sees the pulpit, the choir and the setting and together what makes the setting. Or he goes to the opera, or he goes to a play, or more important, he simply walks his way with his friends. What strikes me is how many students I talk with reflect what college was like. How many of them think back on the people they knew. They looked for what those people they knew stood for and meant to them. I want my students to try to embrace every gesture of friendship.

Yeats has a poem I love, and I’ll recite it for you:

I went out to the hazel wood,

Because a fire was in my head,

And cut and peeled a hazel wand,

And hooked a berry to a thread;

And when white moths were on the wing,

And moth-like stars were flickering out,

I dropped the berry in a stream

And caught a little silver trout.

When I had laid it on the floor

I went to blow the fire a-flame,

But something rustled on the floor,

And someone called me by my name:

It had become a glimmering girl

With apple blossom in her hair

Who called me by my name and ran

And faded through the brightening air.

Though I am old with wandering

Through hollow lands and hilly lands,

I will find out where she has gone,

And kiss her lips and take her hands;

And walk among long dappled grass,

And pluck till time and times are done,

The silver apples of the moon,

The golden apples of the sun.

(Editor’s note — Wilson recited the entire poem, “The Song of Wandering Aengus,” by William Butler Yeats, from memory, without one mistake)

Ed Wilson in 1994

Ed Wilson: Now on the face of it, that seems like a kind of fairy tale. But actually, what he is talking about, is being alert to life, and, being alert, in remembering the people who made his life possible. So that they’ve all flashed before his eyes, things from the past that give his life meaning.

So, for example, if I look at the world, I might see a girl like Debbie and all of a sudden, my life becomes rich from having known her. I want my students to feel these things.

I remember little things from my college experience. I was sitting one day in the hall outside my classroom when I was a student. I was trying to decide how I was going to shape my life in college. Dr. Edgar Folk came by; he didn’t know me. But he saw me sitting there, noticed I was by myself. He came over and asked me what I did. I told him, I was an English major. He taught English. He said, “Do you ever think about writing?” And I said: “Well, I don’t think about it as well as I should.” And he said: “I want you to come to the Old Gold & Black office one day. And I’ll give you a story so you can take that story and make it into a story of news value.”

In that one moment, I became introduced to the newspaper world at Wake Forest. As it turned out, that would not have happened if this one good man had not, for no particular reason, sought me out. I think it is that kind of experience, which ought to be at the heart of college life — an experience which embraces the world we live in, the world we would like to live in, and the world we want to be part of — and the world that somehow will encompass us and bring us together through love.

Debbie Best in 2013

Warren Anderson: Debbie, Ed concentrated on literature and romantic poetry, but you’ve focused on science and research studies. What have you wanted your students to take out into the world after college?

Debbie Best: I think it’s obvious that one of the things that Ed and I share is we want our students to be able to see and observe what’s happening in the world around them. One of the things that we do in psychology is we observe, we watch people. I am a developmental psychologist. So, I’m constantly telling my students, look at what kids are doing, don’t just let somebody tell you about them, watch them, see what they do, because watching them tells you what’s important to them. For my students, I do the same thing. I want them to be observant of the world, I want them to see other people, I want them to interact with other people in a way that’s appropriate. That’s something that’s going to be valuable to them long term.

The students are taught to know what this person is all about, what their motives are, where they want to go, what’s going on and what’s happening in their lives. Then they can march forward with that. I think along with that I have a strong desire for my students to have what I would call “intellectual curiosity.” It’s really important for them to want to know why. I spend a great deal of time trying to figure out the little whys in life, and I try to encourage students to look at those little whys. Why did something happen? Why did this happen? Fortunately, these days, we have Google (laughter) so I can search many of those things. But again, it’s that sort of intellectual curiosity, about life, about people, about the things that are happening around them — that is really the most important.

Ed Wilson in the Rare Books Room in the Z. Smith Reynolds Library in 2014.

Ed Wilson: I certainly agree. When you teach, as Debbie knows, you have a room of 20, 25, 30 students. I made a point of being in my office every day before class. Typically, my class started at two o’clock. Some students would get there a little early and I arranged to be in the office about 12 o’clock, to be on the scene before the class begins. Some of the things that happen to the students in my dealing with them happened, not in what I talked about in the classroom, but what we discussed alone, between the two of us. The teacher has to cover his subject, he has to be aware of his subject, he has to have read what he needs to read, and he has to be alert to the latest interpretations if he’s teaching literature. So, he reads whatever he can in those hours between classes because the interpretation of the literature from those hours of study is left to him to carry along. This must be true or there would not be differences in teachers.

Let me give you an illustration. When I was in college at Wake Forest, I took a course in Chaucer. We studied the “Canterbury Tales” day by day. Our professor had gone on a trip to Canterbury one time, brought his notes back, showed us pictures and told us how he felt when he was there. He wanted to see what Chaucer saw. That was one of the most valuable courses I had in college. I went to graduate school, and I took the course in Chaucer again. My professor was one of the leading Chaucer scholars in the country, he had written books on Chaucer. But when he came to teach the class, he simply summarized what he had read and what he had written in the books. He did not try to bring in what the relationship was between Chaucer and me, the student. So, which was the better course? The famous scholar who had published about Chaucer, but never had burrowed deep into the man and the place of Canterbury? When I went to Canterbury later I saw and experienced what I had learned from the man who made me want to see it for myself. What I experienced was more of what I learned from him rather than the man who had written scholarly books about it.

I think what a teacher has to learn is that curious circling of the people he teaches. He has to know what it’s like to go into the classroom as a student. The teacher must be prepared — not just to tell the story, but also to talk about the meaning of the story, talk about the way the story relates to life, to the life we live every day. If that happens, then the student becomes alert to the world and the values around him. This might involve politics. I have strong opinions about politics. I let my opinions sometimes creep into my speaking. That should not affect my teaching Chaucer or Wordsworth but it can be illustrative material out of my own life.

Debbie Best at Commencement in 2023.

Debbie Best: I do the same thing. I’m teaching about developmental psychology, most of the time, cognitive development or cross-cultural, and in all those situations, I’m talking about my own life experiences. Some of my students laugh and say, “I feel like I know your son, although I’ve never met him.” My personal stories bring the teaching to life. They see what I’m talking about when I illustrate with my son what he did at a particular age. I’ll say: “This is what we see in psychology when we’re looking at kids this age.”

With my cross-cultural studies, I have, fortunately, traveled around the world attending conferences and teaching. I have friends that are colleagues, and I use videos they have made about some of their projects. I have one very dear colleague, Heidi Keller, who is German, I use one of her videos. In class I talk about Heidi and our studies together, that we were doing this and this and this. I think that teaches students there can be a friendship engagement in science because you’re together searching for answers, you’re asking questions of each other, that take you to the next level. It’s one of those interpersonal things. My students laugh and say, “I feel like I know some of your friends.” That brings the classroom material to life, exactly as Ed is saying.

Ed Wilson: Yes, we’re talking about the same thing. As a student I wrote a column for Old Gold & Black called Pro Humanitate. I wrote a column (once) that was very critical of some things I saw around Wake Forest that I didn’t like. I wondered how people would react to it. Shortly thereafter, I was walking across the campus and coming toward me was Dr. Hubert Poteat (1906, MA 1908, P ’36, ’40), who was, in some ways, the most famous of all the Wake Forest faculty. He taught Latin, he had written books, he had lectured, he had lived the life.

When you went to his class, you found yourself transported back to ancient Rome. As Dr. Poteat saw me coming, he took off his hat, and he bowed low in front of me. Which was his way of saying: “Thank you for that column.” That meant a lot to me. Things like that stand out. Wake Forest at its best, I think, has been a college for teachers. It’s also a college for scholars, but mainly a college for teachers.

Ed Wilson at Commencement in 1990

Debbie Best: It’s wonderful when you can put the two things together in a student’s life. When they’re in my lab I watch the light bulbs flash. I see that something that we’ve read and talked about in class, suddenly they understand it because they’re now actually looking at the data. It’s magic.

Ed Wilson: We move into the lives of the students and inhabit their lives enough to show them what is good about us. What is important about us. Not because we are proud. I have known faculty members of Wake Forest who have never cut the tie between teacher and student.

Debbie Best: Both Ed and I have had students to our homes. They understand who we are, how we live, what’s important to us, and they feel very comfortable. I have had a number of students that have graduated, and their children come to Wake Forest. I’ve taught generations now of students. They will show up at my door and say, “Professor Best, my son or daughter is now here at Wake; I want you to show them the magic that I found.”

I’ve taught at our Venice campus and visited for years. It’s an absolutely magical place. You wake up in the morning and as Professor (Terisio) Pinignatti used to say, “The light is so beautiful.” And he was right. Our students get captivated by this unique setting, and we live with them on a daily basis. We see our students in class, and it’s a fairly formal relationship in the class. But then, you see them in their pajamas, eating breakfast, it’s different. It’s fun to watch their lives and for them to watch our lives. I had my young son with me when I was there. He couldn’t have had more playmates and babysitters: “Can we take care of Eric and do so and so?” There were a lot of fun things that I don’t think we would have seen if we hadn’t been living with them.

Then-Dean of the College Deborah Best presents the Jon Reinhardt Award for Distinguished Teaching to music professor Stewart Carter at Fall Convocation in 2007. <br />

Warren Anderson: Tell us about two of the famous athletes you knew at Wake Forest — Arnold Palmer (’51, LLD ’70) and Tim Duncan (’97).

Ed Wilson: I’m a basketball enthusiast. I have typically gone to all the basketball games. But in the last year or two, it has been difficult for me so now I watch the games on television. One player I remember so well was Tim Duncan. He had such a great career here. When he retired, he was interviewed about Wake Forest. No president of Wake Forest could ever have better said what he said about this school and his career here. Not all players are like that. But Tim Duncan was like that. He represented success in the human arena as much as in the basketball arena.

I was in school with Arnold Palmer, on the old campus. One day I went over to an area by the lake where you could hit golf balls over the water. I saw a young fellow who had come down from Pennsylvania. I watched him hitting balls over the water. I knew I was in the presence of a potentially great golfer — I didn’t know he would be the greatest golfer.

We got to know each other. We’d talk about golf. He gave as much time to me talking about golf, as I did to him talking about literature. We became good friends. I was scheduled to be at an alumni meeting in Pennsylvania one time. Arnold Palmer was to be at that same meeting. But I was in a distant town in Pennsylvania meeting with other alumni, and I had to travel a great distance to get to the meeting with Arnold. Arnold called and said, “Get yourself ready. I’m going to fly over and pick you up.” Sure enough, he flew to where I was, picked me up and we had a good talk all the way to our destination. We put on a show. I was with our most famous alumnus but that did not keep us from being generous friends — and we savored those same qualities in other people.

Ed Wilson in 2014

Debbie Best: One of the fun things about Arnold Palmer I remember was when he was one of the tri-chairs of the Heritage and Promise Campaign (in the 1990s). We worked on the campaign together. At the end of the campaign, they asked Arnold to speak at Wait Chapel. We’re lined up on the steps of Reynolda getting ready to walk over to the Chapel where he’s going to give his talk. He tapped me on the shoulder and asked, “Is the Chapel going to be full?” I said, “More than likely, yes, because you’re here.” And he said, “I’m really nervous.” I was surprised and said, “Arnold, you can’t be nervous. You’ve been in front of much larger crowds.”

He said, “But I don’t talk. I don’t give lectures, I don’t do the things you do in a classroom.” I looked at him and said, “That’s OK. You just think about this — you have an eagle putt, you’re on number 18 and to win the tournament all you have to do is make a three-footer — you can do that!” He sort of laughed and went and gave a lovely talk. We get back outside, walking up the steps, he grabs me by the arm and asks, “So how did I do?” And I said, “Oh, man, you had a hole in one!” He burst out laughing. He was so happy.

There’s another anecdote from that same time. It was 1995. Wake Forest had just won the ACC championship in basketball, and the campus was crazy. We had a celebration dinner for the fundraising campaign at Old Town Country Club. I had to give a toast. I was the only woman giving a toast.

I followed several men who gave toasts and had to walk across the room to get to the podium. My high heels were clacking across the floor making noise and everybody’s staring. In my toast I likened each person in the campaign to our winning basketball team. Arnold Palmer was Tim Duncan. And I said Ed was Randolph Childress (’95, P ’20). I mentioned that Ed came into the final part of the campaign with four seconds left before the end of the game, and put in that winning shot, just like Randolph did against Carolina to win the ACC. I said Ed brought us across the finish line, just like Randolph did. Ed told me that was the nicest thing anyone ever said to him.

Ed Wilson: It was.

Debbie Best with Tim Duncan

Debbie Best: You asked about Tim Duncan. Tim used to hang out at my house. It all started with Dave Odom calling me and saying, “I have this basketball player; he wants to be a psych major. And he would like to have an adviser who understands what it’s all about. You are the department chair; will you please take him on?” I said, “Absolutely.”

I was sitting at my desk one day, and this shadow comes over my desk, and it’s Tim walking in the door. We talked for a long time. A few weeks later, we needed to meet but I had to be home because my son was sick. He asked the department secretary to call my house and ask if he could come over. I said, “Just tell him to walk down because I’m on Faculty Drive, and it’s not that far.” So, he walked to my house, and came upstairs to see Eric, my son, and told him, “I hope you’ll get to feeling better” and that sort of thing. Well, they connected. Eric was nine at the time.

A few weeks later, Tim and I were talking about his studies and he said, “Would it be OK if I visited occasionally and saw your son?” And I said, “Of course. Come on.” So, I would get home from work some days, and my son and Tim would be upstairs playing. He ended up staying for dinner fairly often. He would sit on the floor in my kitchen with his feet up on the cabinets while talking to us. I realized he was so tired of looking down at people it was probably nice for him to look up.

I came home one afternoon and heard all this commotion upstairs. My son had a huge collection of stuffed animals. I walked up the steps, looked in Eric’s room and in one corner, there was a little fort built of stuffed animals. Another fort was set up across the room, and Tim and Eric were playing war — throwing stuffed animals at each other across the room. I laughed and thought: “What’s the NBA gonna think about this?”

A few months later, I get a phone call on a Sunday evening. It’s Timmy. He asks, “Doc B, what are you doing?” I said, “I just got home. If you need dinner, come on over.” A few minutes later I look out the back window and there he is on rollerblades! I said, “What in the world? All you got to do is fall and you’ll never play your first year in the NBA!” Timmy said, “Well, David gave them to me,” referring to David Robinson, the star of the San Antonio Spurs, the team that had just drafted Timmy. Tim explained he wanted to do what he could for the “twin towers.” But I’m going, “Timmy Timmy, Timmy! No, no, no, no more rollerblades. Give them to me. I’m taking you home.”

He’s been a lovely friend. We got to visit him fairly often in San Antonio. I’ve been to his house, played with his kids, met his family, and have just really enjoyed him. Just like Ed said, he brought these wonderful values with him to Wake Forest, nurtured them at Wake Forest and has never changed as a quality person.

Debbie Best congratulates a student at Commencement in 2006.

Warren Anderson: Debbie, you’ve had a great relationship with former students, helping them get into graduate school and continuing to stay in contact with them through their post-graduate studies.

Debbie Best: Sometimes it’s a student that I’ve not had in my lab, or that I’ve not done research work with directly. Still, based on what has happened in the classroom, they feel comfortable asking questions of me. So, they’ll stay a few minutes after class and we’ll have a conversation which opens the door for them to send me a follow up email and say, “I’ve been thinking about graduate school, but I don’t really know whom to ask, I don’t know what to do, whom should I talk to?” And happily, they come in, and we talk about what the process is and what they need to do. I’ll say, “Here’s your homework assignment, you go off and do that, come back, and we’ll talk some more.”

It’s a process of getting to know them. Some of them will say that they may be interested in a particular field of psychology but know that is not my area of interest. I’ll laugh and say, “This is you going to grad school, not me. I chose what I chose, and I chose it because I love it. And I love it on a daily basis. I can’t think of anything I’d rather be doing. But you need to figure out what you want. What do you see yourself doing five years, 10 years down the road? What really turns you on, as you’ve sat in these classrooms at Wake Forest, or as you’ve read things?” They end up doing a sort of self-examination, they undergo introspection, thinking about what they want to do. Sometimes they chose to do further graduate study that even surprises their friends and family members, but it is the path they have chosen.

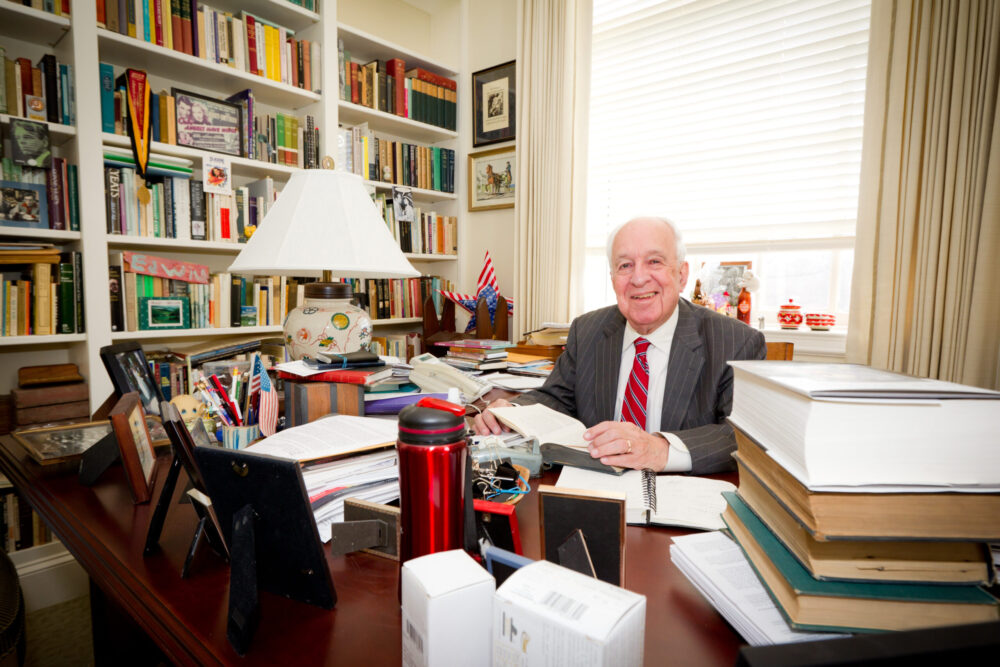

Ed Wilson in his office in the Z.Smith Reynolds Library in 2011.

Warren Anderson: What is a place on the campus that is special to you, a sacred place for you?

Ed Wilson: I loved the office I had years ago in the library. Even after I retired and wouldn’t go into the office very often, I’d get a call from my assistant, Tanya, with messages left for me. She still sends me messages that she thinks might not have gotten to me here at my home, where Emily and I live. I tried to make sure, in putting a staff together, to make sure that the staff has an understanding of what Wake Forest is. Tanya has it. I think my old office might end up being the location where my archives will be located. I continue to get letters from former students who ask that their letters about me get put into my archives.

Debbie Best: My special place is Greene Hall, which houses the psychology department. As Ed will remember, we were in Winston Hall for many years sharing with biology, then biology got a new wing but psychology didn’t get a square foot. We were so cramped. We loved being their neighbors, because we shared a lot — I teach genetics and a lot of brain development in my classes. So, it was good, the coffee pot conversations were valid, they were useful.

But when we planned Greene Hall it was wonderful, because we got to plan the space that we needed to be just the kind of space we could fully use. It’s turned out wonderfully. I’m very proud of having had something to do with planning and building that building — with my architect and friend, Bob Beck, Ed’s neighbor.

Debbie Best in her Greene Hall office in 2013.

Warren Anderson: Provost Wilson, you’ve taught the Holy Grail. What clues would you give us to search for the Holy Grail?

Ed Wilson: Well, first, put into your head what the Holy Grail is. You might decide that the Holy Grail is the cup out of which Jesus drank. But you might decide that it is a cup out of which anybody who reflects on Jesus drank. Or you might decide that it is the cup that is in your hand whatever your religious beliefs might be.

I think the Grail involves a kind of commitment that you have spent a life that has been valuable. You don’t say that in any proud way. I’m sure when Debbie or I speak, we’re not talking about anything that is uniquely ours, we’re talking about something that can be grabbed and used. The Holy Grail can be something that appears from almost anywhere, outside yourself. But it has a connection with yourself, so that it could not exist without you.

Warren Anderson: Debbie, can you try to summarize what Ed Wilson has meant to the Wake Forest community?

Debbie Best: Oh, my goodness. I think Ed personifies Wake Forest in many ways. The intellectual side, the academic commitment, but also that kind warmth, that understanding of students, of faculty colleagues. He is the presence in our lives on a day-to-day basis that really matters. You feel like Ed is always with you. He’s always there. You always know he’s got your back. So, I think Ed is, although the campus is beautiful, and the buildings are beautiful, I think Ed is the personification of all that is good and beautiful at Wake Forest.

He’s been such a wonderful guide for me throughout my career. I was not an English major by any stretch of the imagination. But I read constantly, and I was sitting there a few moments ago, as Ed was quoting Yeats, and I could quote it with him. It’s funny — you don’t think about those things that often. But that connection across disciplines enriches what Wake Forest does, it enriches who we are. And that is a guiding light.

I recall when Ed was Provost, and I was chair of psychology. As I mentioned earlier, we were planning our new building, Greene Hall. Bob Beck, who was my mentor in the department and a senior colleague, and I came to see Ed because we knew we needed lab space and equipment. The psychology department never had lab space. Such a request had to go through the Provost. So here we are two scientists going to see an English professor/Provost, to ask for lab equipment. Bob and I had the numbers, and we had the information we had gathered from our colleagues about the kinds of things that we all needed to run these labs.

We went into Ed’s office and made our presentation. I was expecting him to say: “Well, I don’t understand what this is about, or Why do you want this or that?” Instead, Ed says: “It sounds absolutely perfect to me. And why don’t I add a little bit more money on this side? Because I think you will need that.” He was not just an English professor. He understood the whole University.

Then-Dean of the College Ed Wilson in 1966

Parker Beverly (’23): Since you both were students at Wake Forest, what was that transition like from being a student to a professor?

Debbie Best: Mine was most interesting because I was an undergraduate and I stayed at Wake to get my master’s. I started teaching immediately. I was 23 years old (laughter), so I’ve been doing this a long time. I remember my first class. This was the Vietnam era. Some of the people sitting in my class had been undergraduate students who had gone to Vietnam and come back. These were young men who used to sit on the PKA fraternity wall, if you will. We used to walk to the post office to get our snail mail. The guys sitting on the PKA wall would sometimes whistle and make ugly statements to the girls. I looked out into my classroom, and I saw three of these PKA-Vietnam veteran guys sitting there.

I also saw Kathy Janeway (P ’85) sitting in my class. Her husband, Dick, was dean of our medical school. Here I am 23 years old. I had done some teacher’s assistant work as a graduate student, but I had never taught. I was terrified. So, I got through the first class, then I went over to Bob Beck’s office and said: “I can’t do this.” He looked right at me and said: “Of course you can. You’ve crossed to the other side of the desk, and now you’re in charge. Those boys who’ve come back from Vietnam, they’ve learned some lessons. They’ve learned what life is. They’re here because they want to be here. And the dean’s wife, why she’s a lovely person and she’s very curious. She will want to know anything and everything you can share with her.” So, I gathered up my strength and my courage and went back to teach the class. It was one of the most fabulous experiences I’ve ever had.

I kept trying, in those younger years, to get used to “being on the other side of the desk,” because there were some awkward times where a student my age or older felt like they could take advantage of a young teacher. I had to learn to be stern, I had to learn to be “on the other side of the desk.” Wake Forest students are very respectful. I think they truly are here because they want to be here. They’re not here because their parents make them come. They’re intellectually curious. They want to know, they want to learn and they want to grow. Knowing that we were in this together — that I’m their teammate in this growing process — 99% of the time, they have been wonderful to work with — even when I was so young.

Debbie Best and Parker Beverly at Commencement 2023.

Ed Wilson: Well, I had a very happy experience. Freshman English unit was mostly writing themes — we had to write a theme every week. Half the themes were written at home and half the themes were written in class. I was assigned Max Griffin as my freshman professor. Early in the semester Professor Griffin called me into his office and said: “I’ve been reading your themes. You don’t need to write the kind of themes that I’m asking the other students to write. I’m going to give you a special assignment in writing. You can forget the class as far as the themes are concerned. I want you to write for me. I’m going to give you a subject to write upon every week. You take that subject and write that.” And I did.

So, I was picked out among a group of 30 or 40 students and given free sailing by a faculty member who wanted me to get the most possible from Wake Forest — the ability to write and the ability to do something original without having it forced upon me. And that’s what I did. Every week. He would pick a subject, like “sunrise and sunset, write something about that.” That made a tremendous difference, giving me a great start and contributed to where I am today.

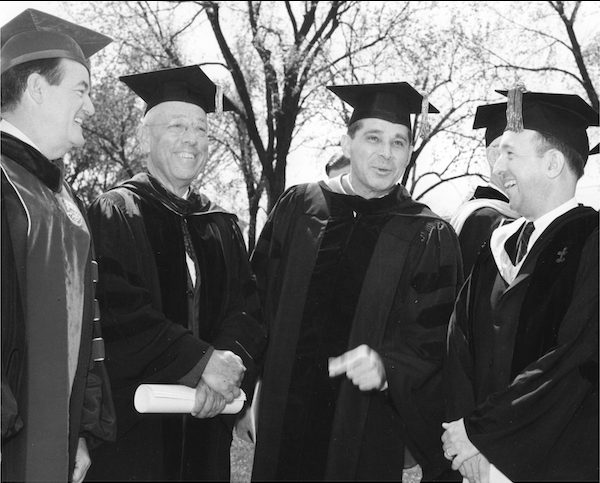

Vice President Hubert Humphrey, outgoing Wake Forest President Harold Tribble, new President James Ralph Scales and then-Dean and later Provost Ed Wilson.

Debbie Best: Ed, when you came back to Wake Forest as a faculty member many of those same faculty members you had as a student were here. Was that a comfortable transition for you?

Ed Wilson: It was easy because so many of them were already special friends of mine. President (Harold W.) Tribble (LLD ’48, P ’55), who was president during the mid-60s, never had a Provost. There were deans — dean of the law school, dean of the medical school, dean of the College — all of whom reported directly to the president.

Dr. (James Ralph) Scales became president (in 1967) and thought we should have a provost, so he asked President Tribble if he could establish a provost position and if he could select me. Dr. Tribble knew me well and said: “Great, that’s fine.” I asked President Scales later: “Why did you ask me to become Provost?” He said: “Because I trust you.” It was as simple as that. But that says a lot. Not about me. But about how important it is in the administration of our college for us to trust one another. I trust Debbie. And I trusted the deans I worked with over the years.

Debbie Best: When you asked what Ed has meant to the University, I think he embodies that trust that we have with each other that we’re going in the same direction, taking the same pathway, and we’ll help each other get there.

Ed Wilson: Thank you, Debbie.

Ed Wilson in 2003