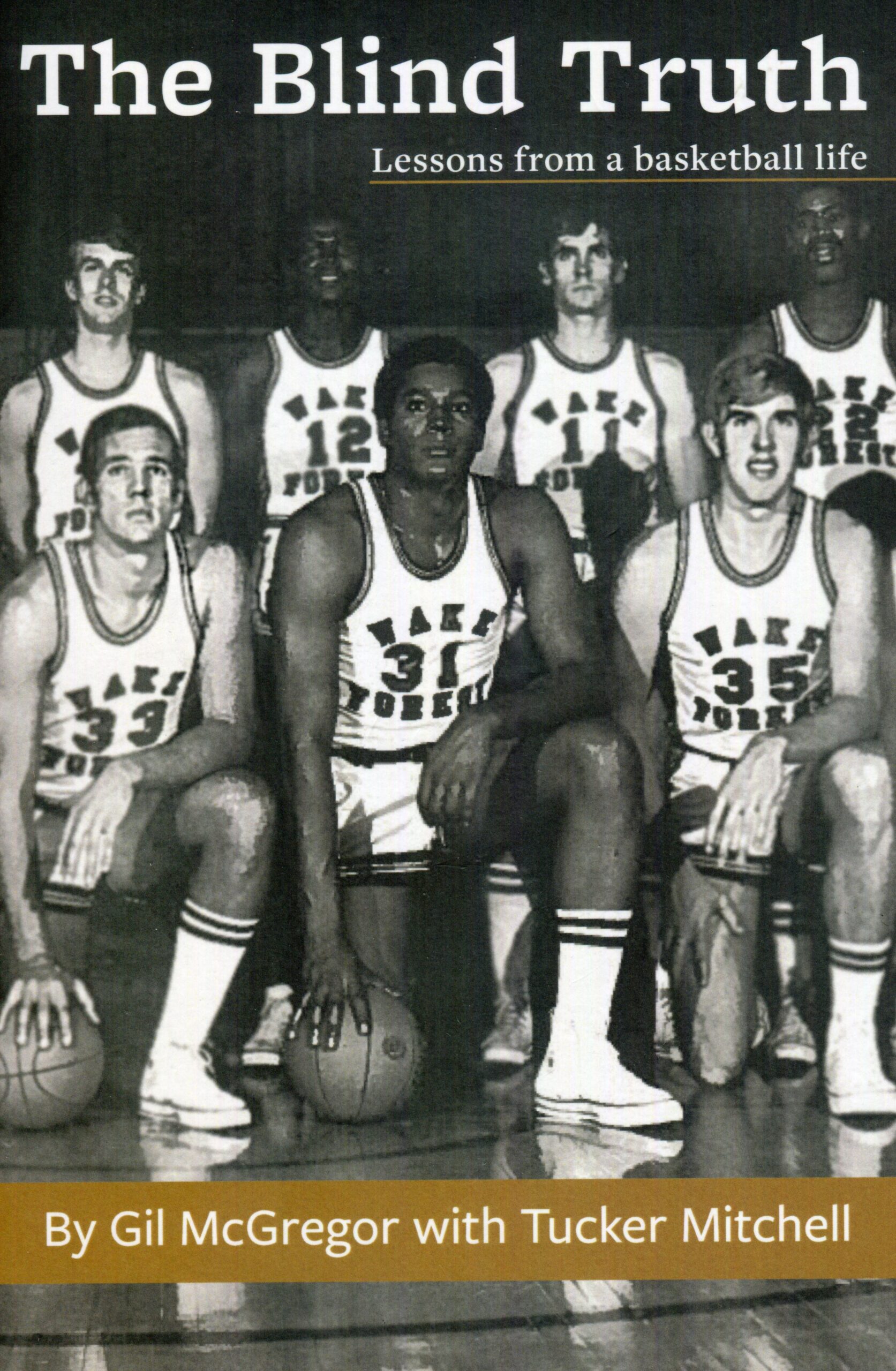

Gil McGregor (’71, P ’16), one of the first Black basketball players at Wake Forest in the mid-1960s, did “some uncommon things” and lived “in interesting times,” as he writes in his new memoir, “The Blind Truth: Lessons from a basketball life.”

He writes honestly, poignantly and, at times, humorously, about his life and the lessons learned — from growing up in the segregated South and the challenges he faced as one of the first Black students at Wake Forest to his professional basketball days and long broadcasting career with the Charlotte Hornets.

His biggest challenge – glaucoma – came more than a decade ago. He began losing his eyesight, but he was gaining insight. “Day by day, month by month, oh so slowly, it dawned on me that my ability to perceive, to understand and to comprehend the ups and downs, the ins and outs, of life itself was getting better. I could see things I had never seen before,” he writes. “Everywhere my mind turns, as it strolls down memory lane, I can ‘see’ what I like to call blind truths.”

“The one thing that stands in the way of greatness more than anything else is ‘good enough.’ When you say it’s good enough, you limit yourself.”

McGregor, 75, grew up in Raeford, in eastern North Carolina. McGregor and New York native Charlie Davis (’71, MALS ’97, P ’96 ) came to Wake Forest a year after Norwood Todmann (’71) became the first Black basketball player at Wake Forest. (Davis later gained distinction as the ACC’s first Black basketball Player of the Year.) After a standout college career, McGregor played briefly in the NBA and for a decade in Belgium, France and Italy.

He returned to Wake Forest in the mid-1980s as the academic adviser for student-athletes. He began announcing college basketball games and then joined the Charlotte Hornets as a television and radio broadcaster during the team’s first season in 1988. His broadcasting career came to an end in 2012, as he was losing his vision.

McGregor wrote his memoir with longtime journalist Tucker Mitchell (’78). Mitchell is also the author of “Peahead! The Life and Times of a Southern-Fried Coach” about Wake Forest football coach Douglas Clyde “Peahead” Walker.

Wake Forest Magazine Senior Editor Kerry M. King (’85) recently talked with McGregor and Mitchell. Their conversation has been edited for brevity and clarity.

Gil McGregor was a broadcaster for the Charlotte Hornets for 24 years.

Kerry King: Gil, you write about lessons learned, including the importance of taking a stand, how it takes a whole team to succeed in basketball and in life, and the importance of finding a mentor and then being one yourself. What’s one of your “blind truths” that you would like to share with alumni?

Gil McGregor: When Willis Reed (who played for the New York Knicks) was on my podcast, I asked him, “It’s the end of the game. The clock is running down, and you’re behind by one point. You have the ball, and you get to take the last shot, knowing that if you miss, your team loses. How do you handle that?” And he said, “Gil, we’re already losing the game. All I can do is win it.”

If we have the mentality that all we can do is win, then we can be champions. But most people only think about losing. That’s where we need to have our heads about life.

KK: You were in the first group of Black students to integrate the all-white high school in Raeford. I read in your book that you weren’t looking to make a statement. You just wanted to go to a better school. And then you were one of the first Black basketball players at Wake Forest, but you seem reluctant to call yourself a trailblazer. Why is that?

GM: I don’t call myself a trailblazer because I was one of the first, but I wasn’t by myself. There were about 20 students who left Upchurch (the all-Black high school) to go to Hoke County High School. I don’t know how many came from Hawkeye (the Native American school). We didn’t have a lot of problems, there weren’t a lot of disruptions or fighting, and not a lot of racial issues that I can recall. I thought that was a good start, and I was part of that start.

I can recall being on an activity bus going to a game in Dunn (North Carolina) and seeing a billboard on the side of the road with a picture of a klansman on a horse, and the sign says, “Welcome to Dunn: Fight integration and Communism.” Seeing that didn’t make my foul shooting any better, but we gave it to them pretty good that night, and I got my revenge.

Going to Hoke was not part of some movement. My parents and I didn’t go to a church where there were a bunch of people saying, “You have to represent the Black community and go to the white school.” My parents just said, “What would you like to do?”

In 2017, which was the 50th anniversary of my high school graduation, I was asked to come back and be a part of that ceremony. I didn’t go because I was feeling that things have changed, but not as much as they should have changed. I’m not using the word “token” as it was used back in ’67, but I didn’t want to go back as a representative of how far we’ve come when we haven’t come that far. (In hindsight, he writes, he should have gone. “It’s all right to celebrate past success, but let’s not party too long before we get back to work.”)

"Humanity's default position is to withdraw into groups of like people, and bare teeth at those 'others' who aren't like them. ... We miss a lot by dismissing what we might gain from entire groups of people. That may seem obvious, but I'm always amazed how many people live life that way."

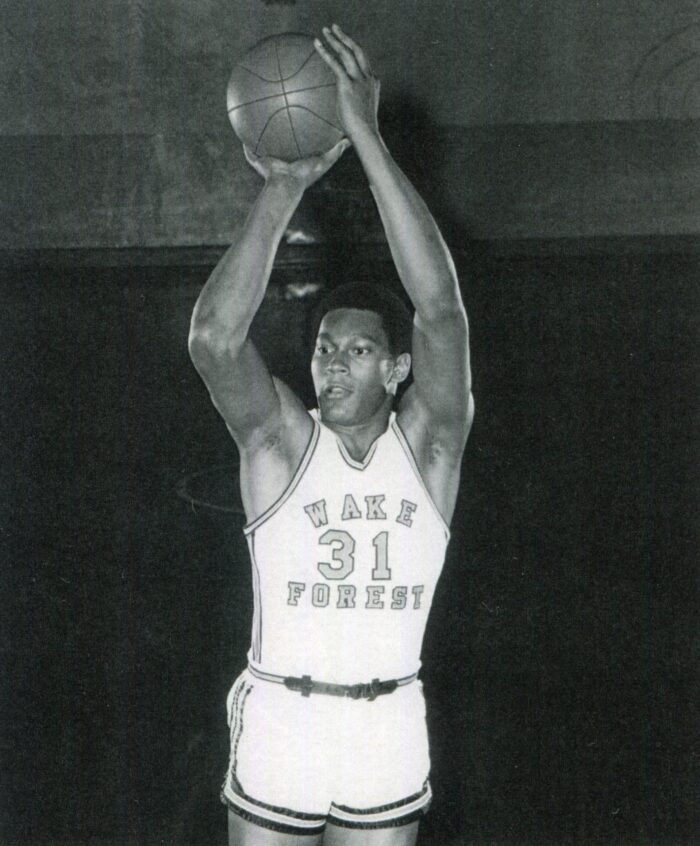

No. 31, Gil McGregor, in a publicity shot before the 1969-70 season. (Photos courtesy of Gil McGregor and Wake Forest athletics)

KK: As a star basketball player in high school, you received a lot of attention from college coaches who would go on to become legends, including John Wooden (UCLA), Dean Smith (North Carolina), Frank McGuire (South Carolina), Norm Sloan (NC State) and Lefty Driesell (then at Davidson, later at Maryland). So, why did you choose to play for coach Jack McCloskey and assistant coach Billy Packer (’62) at Wake Forest?

GM: You might have thought I was pretty intelligent until you read about all those people I turned down. I couldn’t go to UCLA and play center because they had a guy named Lew Alcindor (Kareem Abdul-Jabbar). And I’m an only child, and my mom wouldn’t have been happy about me going to the West Coast.

My first ever contact with a college was Wake Forest. When I was a sophomore at Upchurch, this white guy passed by and said, “Do you play football?” And I said, “No, I play basketball.” I was 15 years old, 6 feet, 2 inches, 6 feet, 3 inches tall, 195 or 205 pounds, so I was a pretty big kid. And he said, “Well, just take this information sheet and fill it out and send it in to us, and we are going to recruit you when you’re old enough.” That was the extent of the conversation. The guy was from Wake Forest, probably an assistant football coach. It was kind of insignificant, but when I look back on it, maybe it was providence that I came to Wake Forest.

Coming to Wake Forest had a lot to do with me being from a small town, and Wake is a small school. It had to do with Billy Packer, more so than Jack McCloskey, because Billy recruited me, and he made me feel at ease. A guy who played football at Wake Forest, Tommy Gavin (’71), came to see me play one night (in high school), along with Norwood Todmann (’71). That impressed me. They were African American, and I point that out (because there weren’t a lot of Black athletes at Wake Forest).

(On a visit to Wake Forest) I was walking around the Quad by myself, and this student came up to me and said, “Are you lost?” He didn’t say, “What are you doing on campus?” It was probably evident that I wasn’t a student because there was so few Blacks. I told him I was visiting Wake. He said, “Well, let me tell you a little bit about Wake.” And we sat down on one of the benches on the Quad, and he talked about how Wake was a great place and how he thought I might really like going there. It was one more sign that Wake Forest seemed welcoming. The pioneering aspect of it had not crossed my mind. It was whether or not I could go there and play in the ACC.

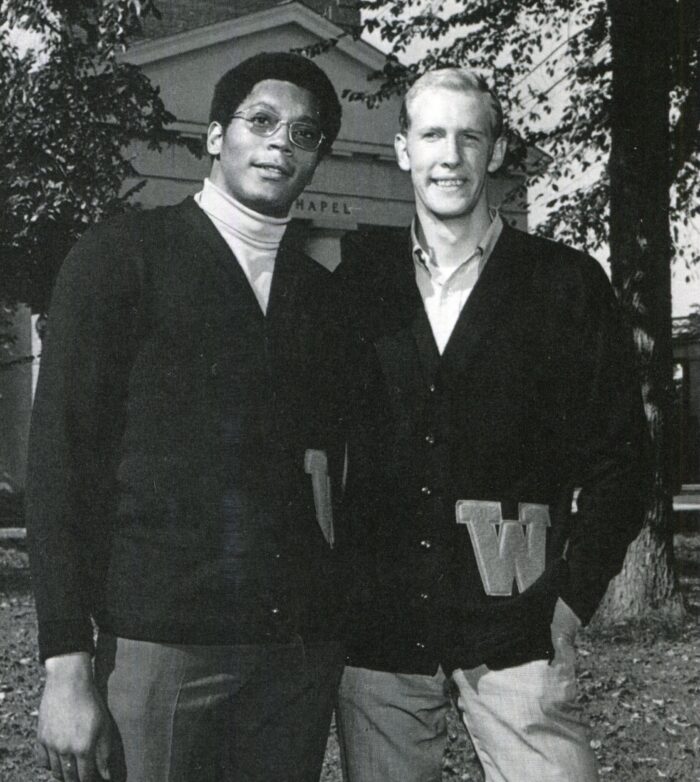

Gil McGregor and teammate Dan Ackley ('70) in a pre-season publicity shot before the 1970-71 season. "This is not what I typically wore to class," McGregor says.

KK: In the book, you write about professors and classmates who made racist comments, but you also mention professors and classmates who were supportive. You wrote that Wake Forest has a “special place in my heart.” How do you look back on your time at Wake Forest, 50 years later?

GM: Wake Forest is such a dear place to me. My son (Gil McGregor ’16) went to Wake Forest, so we have that to share.

Racism was there, but it wasn’t overarching of everything else. I think the lack of interaction between races and cultures breeds a level of ignorance. And sometimes ignorance can be mistaken for racism. Culture has a lot to do with how we perceive things.

In (one) class, the first time I made any remarks in class, a student didn’t know how to perceive me because he didn’t think that Black people could speak well, until he heard me speak. I guess that could have been explained by racism. But it was really his lack of contact with anybody Black who could speak well. So, I had to learn the nuances.

"When I was a student ... I took several stands again racism and other issues in society and on campus. Did I make a difference? The results were not obvious results, but who knows? I might have inspired someone else whose actions brought about meaningful change. ... But what's more important is that I did the right thing. I saw something I believed to be wrong and I did what I could to make it right. That's all anyone can do."

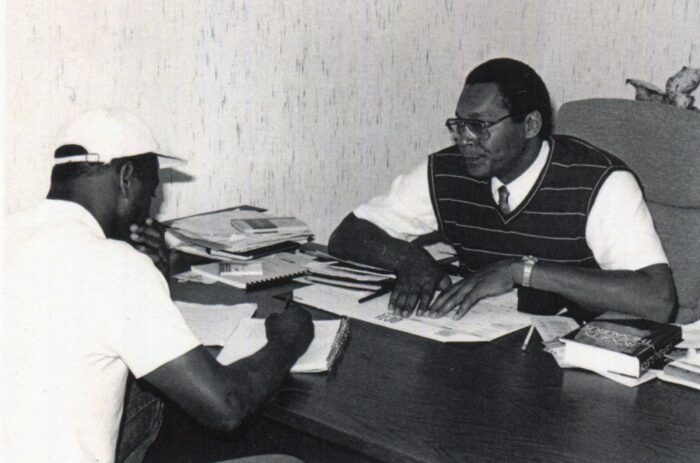

"I wasn't sure what I was getting into when I agreed to become the academic counselor for Wake Forest athletics in the 1980s, but I would up enjoying my work there immensely," McGregor says.

KK: After you played professional basketball, you returned to Wake Forest as the academic adviser in the athletics department — essentially you were the entire academic advising office — in the mid-1980s.

GM: The five years that I was the athletic-academic adviser at Wake Forest has shaped a lot of what I want to say to young people, and to not-so-young people, since I’m not so young anymore. I’ve had a chance to thank (then-athletic director) Dr. (Gene) Hooks (’50, P ’81) for that opportunity. I wasn’t the greatest student. But I wanted the student-athletes to know that they could be successful if they did certain things.

That was probably the start of changing the whole concept of academic advising for student-athletes. I will let you call me a trailblazer for that. I take a little bit of pride in the way things are now.

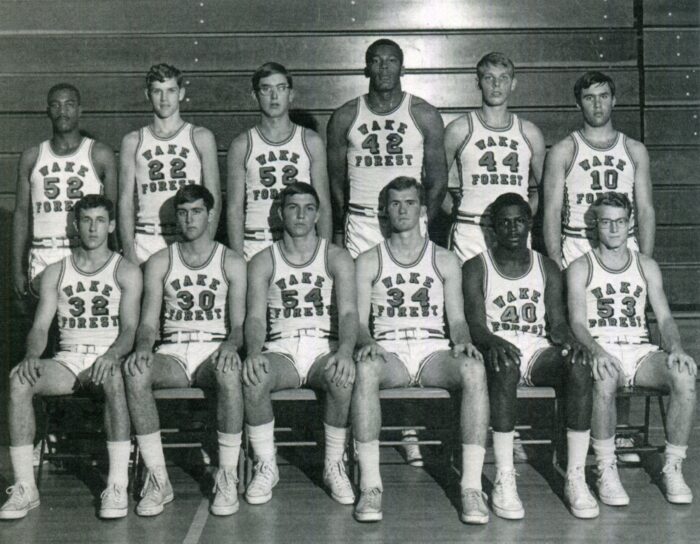

Wake Forest's 1967-68 freshman team (before freshman were eligible to play on the varsity team) included Gil McGregor (who wore No. 42 then) and Charlie Davis (No. 40)

KK: Your long career with the Charlotte Hornets was ending about the same time as you were losing your eyesight. You seem remarkably accepting of losing your sight.

GM: Most of the time (I am accepting), because there’s not anything that can be done about it at the moment. (His eye problems date back decades, including taking numerous hits to the eye playing basketball and suffering a detached retina playing in Italy.) For a long time, I was a pretty good one-eye basketball player. Nobody knew. I hope I live long enough for medical science to work its magic. I’m hoping to be an advocate for research. I did a lot of motivational speaking before losing my sight, and I’m hoping to do that again because I think that there are some things that I call “blind truths” — in a little book you mentioned — that I can impart to people, especially young people.

KK: Tucker, let me close with a question for you. What’s the most surprising thing you learned about Gil?

Tucker Mitchell: I understand what he said earlier that he was not an “out-front” pioneer, but let’s be honest. He was clearly a pioneer: in the first class to integrate his high school, one of the first athletes at a major university who was Black. He did blaze the trail for others.

"I made a career cleaning up other people's messes (rebounding and scoring off teammates' missed shots). .... In almost anything you do, there is a career to be made in cleaning up the mess, in helping others recover from an error or a miscalculation. And best of all, all it usually takes is hard work, some knowledge, and a little patience."