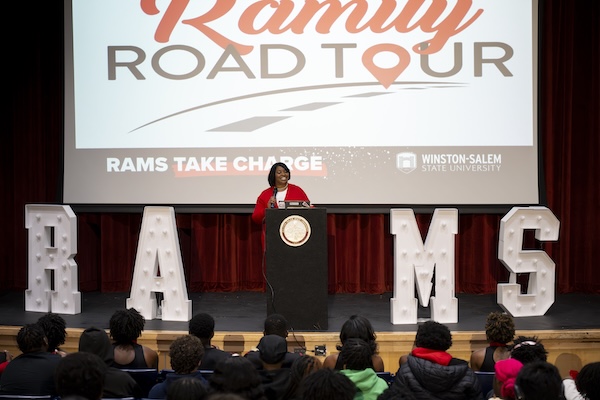

Bonita (Hairston) Brown (’94, JD ’97), chancellor of Winston-Salem State University

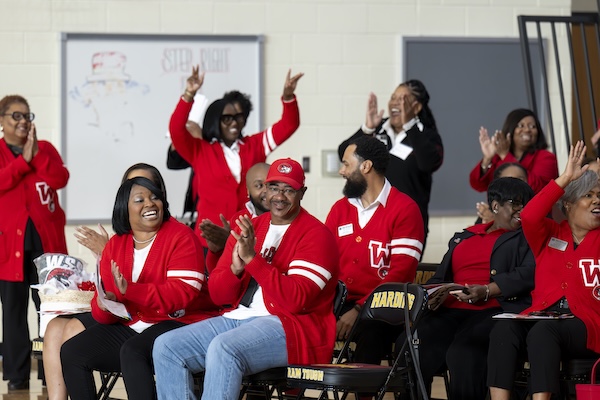

Winston-Salem State University’s high-energy bus tour has been pulling up to high schools across North Carolina since the fall, and leading the charge is Chancellor Bonita (Hairston) Brown (’94, JD ’97).

Traveling aboard a bus wrapped in the university’s red and white, Brown and other Winston-Salem State representatives, along with students from the marching band, choir or cheerleading squad, stop to highlight the historically Black public university’s offerings and extend on-the-spot admissions offers.

They called it the “Ramily” Road Tour—a mashup of the words “Ram,” the school’s mascot, and “family,” which aims to capture the university’s tight-knit community. For Brown, those family ties run even deeper than the connections she’s made with colleagues and students since taking the helm of the 133-year-old university last summer.

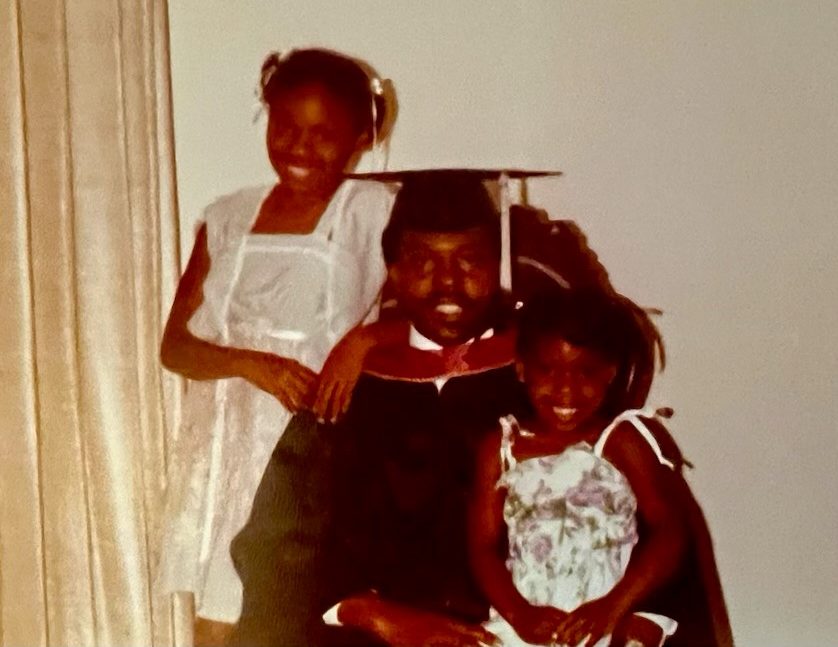

In fact, her connection to the university goes all the way back to before she was born. Brown entered the world while her mother was a senior at Winston-Salem State. When her mom had class, she’d drop infant Brown off at a residence hall with friends. “When I say I have been at this school all my life — all my life,” Brown says.

Bonita (Hairston) Brown (’94, JD ’97), Winston-Salem State University's new chancellor, revs up high school students during WSSU's Ramily Road Tour. Photos courtesy of Brown and Winston-Salem State University

After a decades-long career in higher education that’s been focused on helping students graduate and move up the social and economic ladder, Brown is now leading her parents’ alma mater, which is just several miles away from her own. In many ways, it’s a dream come true for the North Carolina native, who grew up in nearby Davidson County.

“I am having an absolute ball, even on some bad days,” Brown says. “Our work, literally, is building future generations.”

Impact of a college education

Brown knows well how a college education, particularly one at Winston-Salem State, can dramatically change a family’s trajectory. Both her parents grew up in low-income families. Her mother’s community rallied to raise the money to get her to Winston-Salem State.

Her paternal grandfather was a World War II veteran, but like many Black veterans had trouble finding work and securing government benefits extended to White veterans, Brown says. He was eventually able to secure land, only with the help of a white family, to grow tobacco.

Brown spent time working in those tobacco fields, enduring the back-breaking work. She quickly realized she didn’t want to do that forever. “It was my fastest track to college,” she says.

For both her parents, a college education was transformative. With a degree, Brown’s mother became a teacher and later served as a principal in three elementary schools.

About a decade after her mother finished her own degree, Brown was sitting in on evening classes at Winston-Salem State with her father. Returning to college later in life, he earned a degree that helped him climb the management ranks at R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company, now a unit of Reynolds American Inc.

College — especially Winston-Salem State — was a central part of Brown’s childhood. As a grade schooler, she twirled a baton in the Winston-Salem State homecoming parade.

When it came time for her to apply to college, however, Brown had lots of choices. Graduating near the top of her Davidson County high school class, she dreamed of Princeton University — until she realized the price and the distance.

She already knew law school might be in the offing, and Wake Forest had everything she wanted — a partial scholarship, a campus close to home and a law school. “When I went to visit Wake, it felt like I was at home already,” she says.

These days, when she tells students about her Wake Forest years, she uses herself as an example of what not to do. Brown didn’t get very involved with on-campus activities. “If I had to do it over, that’s the one thing I probably would have done over,” she says.

She did, however, connect with two professors at Wake Forest who provided Brown with the space and place to just sit or seek advice. Simone Caron, a history professor, recognized that Brown was disconnected at times and took her under their wing early on. Brown, a history major, eventually became a regular in Caron’s office.

In law school, it was Professor Simone Rose (P ’16), one of Wake’s first Black female law professors. “(Rose) was young, and she was bright, and when she came in, I was just in awe,” Brown remembers. Rose, who taught patent and trademark law, influenced Brown’s decision to focus her studies on corporate law. “I took all of her classes,” Brown says.

After seven years at Wake Forest, Brown struck out on her own. Its Pro Humanitate motto became a guiding force. “It resonated with how I was brought up,” she says. “It has always been a prime tenet for me as I did my work.”

New job, new career, new opportunities

Brown went into the corporate world, working as an attorney in Washington, D.C., but it didn’t last long. The experience of living through 9/11 in D.C. sent her back to North Carolina. “I was still young,” she says. “I was scared.”

On a lark, she applied to a job posting for an attorney at Livingstone College, a small, private historically Black college in Salisbury, North Carolina. After an interview with the president, Brown remembers thinking she’d done pretty well — until the president declared that she wasn’t going to hire Brown as the attorney but as assistant to the president.

“I thought she meant secretary,” Brown remembers. “I was like, ‘You know I’m not a secretary, right?’ … And she laughed.”

Brown quickly learned that an assistant to the president doesn’t get coffee; she shepherds the president’s projects to completion. With nothing to lose, she took the job. “I fell in love with it,” she says. “It fit all of my skill sets.”

Six months after taking the job at Livingstone, Brown began moving up the ranks from one college to the next. First came Johnson C. Smith University in Charlotte and then Winston-Salem State, where she was an assistant university attorney. Eventually, her journey included stops at the University of North Carolina School of the Arts, the University of North Texas and the University of North Carolina at Greensboro.

She’s just this incredibly warm person. Even the way she will lead a meeting, she can deliver even the hardest points with a spirit of levity.

Kelley Mills, now Brown’s chief of staff and a vice chancellor at Winston-Salem State, first worked with Brown at UNCSA and UNCG. Mills considers Brown a mentor.

“She’s just this incredibly warm person,” Mills says. “Even the way she will lead a meeting, she can deliver even the hardest points with a spirit of levity. … You never leave a conversation or an engagement with her feeling like you’ve been cut off at the knees.”

Becoming a ‘student of the presidency’

The title of “college president” wasn’t exactly on her to-do list yet. But, in her first role at Winston-Salem State from 2004 to 2006, Brown began studying the career path of higher education leaders. “I wanted to see differences, what made good leaders,” she says. “I literally became a student of the presidency.”

She realized her path to the top would be a bit unconventional. Most college presidents rise through the academic ranks, but that wasn’t Brown’s background. So, for several years, Brown stepped away from a college campus to work for two higher education nonprofits that focused on removing barriers for students seeking a college education.

“It gave me a little bit of that cache that I needed to move forward,” she says.

The plan worked. In 2019, she took on a role as vice president and chief strategy officer at Northern Kentucky University, a public university near Cincinnati. Her nearly six years there included a stint as interim president.

“That was a hard year,” Brown recalls. “We had to create a plan to try to get this place on a path to a balanced budget. … I had to keep the campus calm. I had to get steady. I had to keep us looking towards the future and keep our focus on the students.”

But there were plenty of high points, too. During her time at Northern Kentucky, she helped raise both the persistence rate, which means students continuing to the next term, and also the retention rate, which is the percentage of students returning to the same institution, by more than 5 percent.

And, with Brown’s encouragement, her husband, Wesley Brown, was able to realize his own dream — finishing up credits to earn a bachelor’s degree at Northern Kentucky while his wife was interim president. Her signature — as interim president — is on his diploma.

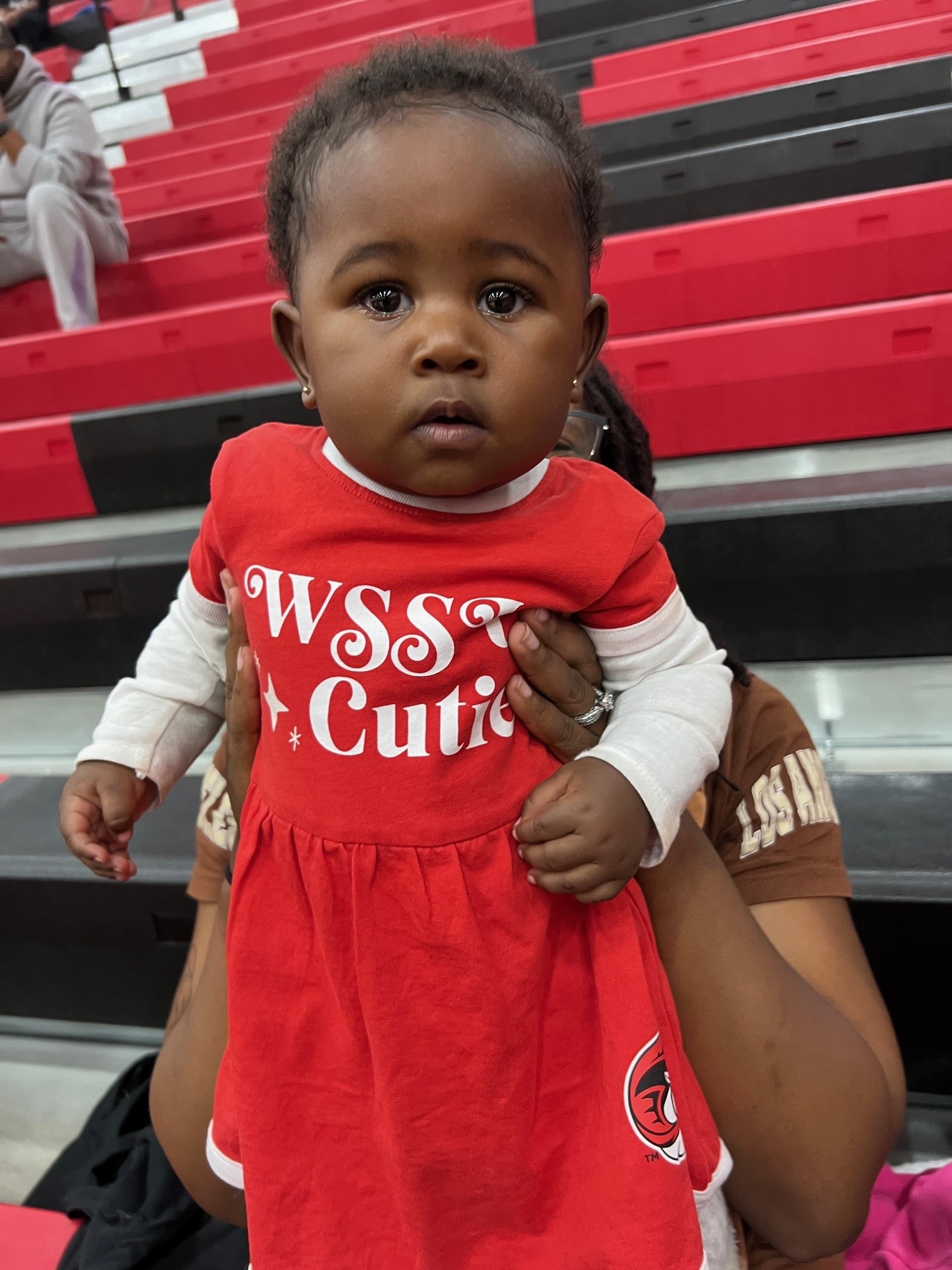

The two met through a mutual friend and married in 2010. Wesley Brown’s first wife passed away in 2008, and Bonita Brown has helped to raise his two children, now young adults. The Browns revel in spending time with a 1-year-old granddaughter.

By the time Winston-Salem State came calling, Brown was ready. She’d interviewed for other presidency roles but hit roadblocks. Interviewers would ask about situations that she hadn’t experienced yet. During the Winston-Salem State interview, everything came together.

“Every question they asked me, I had an answer and examples,” she says. “It felt like a culmination moment of all of my work.”

It’s Auntie Bo

Brown became Winston-Salem State’s chancellor on July 1, 2024, and quickly became an “auntie” in the Ramily. Walk across campus, and students will either shout out a hello to “Auntie Bo” or whisper it quietly in reverence, using a term that’s commonly used in Black communities to show respect to women.

That respect — and excitement — come from her diligent work listening and talking to students across campus, Mills and Wesley Brown say.

“If she’s going to get lunch, she’s intentional about speaking to the students, because she knows that the reason students are here is to get an education, and the reason she’s here is because the students need her to get that education,” her husband says. “Everybody on campus plays a vital role. … Without you, there’s no me.”

In her first year at Winston-Salem State, Brown has spent a lot of time meeting with faculty, students and alumni. She’s focused on student success and excitedly shares big wins, including a recent announcement that plant samples from the university’s Astrobotany Lab will be on the first Blue Origin all-female mission to space.

Another win came through a partnership between Brown’s alma mater and her current university. In October, the two institutions created a pathway for Winston-Salem State students to matriculate into Wake Forest’s law school. The agreement was in the works before Brown took the helm, and Brown finalized it. Brown and Andrew Klein, dean of the Wake Forest School of Law, have known each other for several years.

While Brown was at Northern Kentucky, Klein was interim chancellor of Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis. The two schools played in the same athletic conference. “We were support buddies,” Klein says. “We would talk as we were going through the same thing at the same time.”

When Klein announced during a group Zoom call that he’d been hired to lead Wake Forest Law, Brown unmuted herself to say that she was a graduate — and was serving on his new school’s Law Board of Visitors.

“She just has a charisma and energy about her that is very rare,” Klein says. “She is someone who will roll up her sleeves and tackle any issue and get it done with a big smile on her face.”

Amid budget cuts and other challenges, plenty is uncertain in higher education today. But Brown says she’s ready for the challenges and focused on what matters most — the students. From her own family’s experience, Brown knows how a place like Winston-Salem State can transform personal journeys and family stories.

“I just have to rely on the fact that this institution has been around since 1892, and we have a mission,” Brown says. “Our purpose is to educate students in this region, and we just have to stand on that.”

Sarah Lindenfeld Hall is a longtime North Carolina-based journalist, former staff writer for the Winston-Salem Journal and The (Raleigh) News & Observer and founding editor of WRAL-TV’s popular parenting website. Today, she’s a freelance writer, regularly diving into stories about interesting people and parenting, health, education, business and technology topics.