Dr. Perry Mandanis (’81) reflects fondly on his days at Wake Forest, from science labs to rehearsals in Scales (when it was new) and rock concerts (Pat Benatar) in Wait Chapel. He gamely tackled it all, noticing along the way that he had to work harder and longer than his fellow students to keep up.

Dr. Perry Mandanis (’81). All photos courtesy of Mandanis

It wasn’t until medical school, at The Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University, that Mandanis learned that he had ADHD. That relatively late revelation sparked his career as a pediatric psychiatrist, in which he has devoted much of his work to helping children and adults alike find ways to navigate life with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, he started a podcast, then pivoted to Instagram, where he garnered 250,000 followers — and a publishing deal. But instead of creating a self-help book that he worried would go unread by well-intentioned people with ADHD, he created a deck of cards instead: “ADHDoable: 50 Proven Strategies to Live Better with ADHD.”

Kelly Greene (’91), managing editor of Wake Forest Magazine, recently caught up with Mandanis by Zoom at his home office in Hampton, Connecticut, to hear more about his work — and his countless pairs of colorful glasses. Here are excerpts from the conversation, edited for length and clarity.

Kelly Greene: Perry, your own experience with ADHD seems like the right place to start. You got all the way to medical school before you were diagnosed?

Perry Mandanis: Yes. I went to a really competitive college prep kind of high school, a private school, and it was difficult, but I worked hard.

And then Wake Forest was really difficult, and I often reflected on, “Why are my friends able to play more than I am?” Because I would just put in more hours to keep up. But then when I got to medical school, … the volume and the complexity just exploded. So, during the first year, I thought, “I can’t do this. I’m not bright enough. I don’t know what’s wrong with me.” I saw a therapist, and it was that person who said, “From what you’ve described, have you ever considered that you may have inattentive ADHD?” I saw the neuropsychologist, and sure enough, I had it. And once I got on medicine, I was able to do medical-school work. I was fine after that.

I did a full residency in pediatrics, a full residency in adult psychiatry, and then a full fellowship in child and adolescent family psychiatry. I was moving a desk into my office the very day before I was to hang my shingle at the end of my education. I fell down a flight of stairs and injured my spinal cord. I had to take a year off. And so, the rest of my adult life, I’ve been wheelchair dependent. But I’m so well adapted to it now that I don’t even think about it.

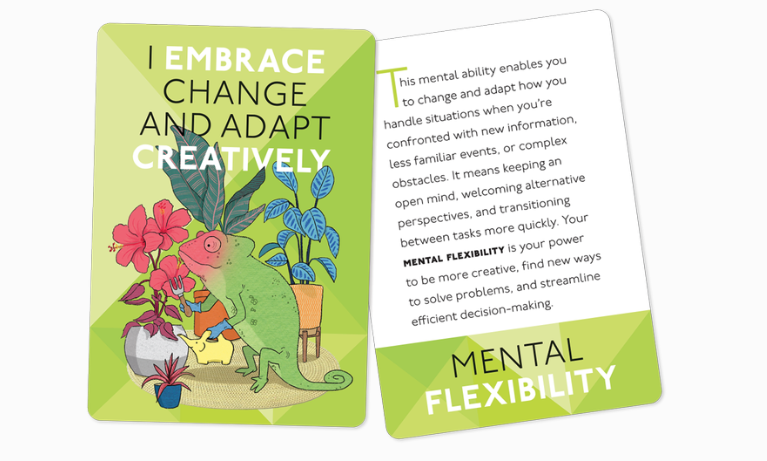

Couch Stories, the podcast that led to "ADHDoable: 50 Proven Strategies to Live Better with ADHD," a publication Dr. Mandanis wrote that's presented as a deck of cards.

KG: That makes your career even more admirable, Perry, and I meant to start by congratulating you on your first publication. How did it come together?

PM: During the pandemic, I started a podcast that was called “Couch Stories,” and … I had some amazing people agree to be interviewed, like Angela Duckworth (a psychologist whose research found that perseverance and grit were better predictors of success than talent and IQ). I would say, “Tell me about a time in your life when you thought you just weren’t going to be able to get through this, and how did you find the strength to persevere?” So, the whole podcast was about resilience, which I thought was a really timely theme during the pandemic, and it did well, but it just turned out to be so much work and it was rather expensive for me to do this.

So, I morphed into social media, which I could do on my own without having to hire a studio and all this kind of stuff. Well, my social media presence took off like lightning. I went from zero to a quarter of a million followers in a year and a half.

And I captured the attention of a couple of publishers who kept saying, “Write a book, write a book, write a book.” And I thought, “I know ADHD people. They will buy the book. They will have good intentions to read the book, they will not read the book, and they will feel bad about not reading the book. I don’t want to be that guy.” I’ve had this idea for a long time about a set of skills cards, and I pitched it to two publishers that were both interested, and they competed to sign me. I really got lucky. And lo and behold, my cards are published.

KG: How did you land on cards, specifically, as a book alternative?

PM: As I’ve worked with people that have ADHD over these many past decades, I just kind of kept a little book in my office of the things that were universally helpful to people, or those tips that a patient would tell me about where I’d think, “This is a great idea. Let me jot that down.” So, I collected these tips, and for the deck of cards, I developed them around the executive functions of the brain. People with ADHD have a challenge in their prefrontal cortex, and that is the area that’s responsible for most of our organizing executive functions — planning, prioritization, task initiation, time management, etc. I organized the cards around 10 of those functions and gave five tips on how you could strengthen your brain and or improve that executive function.

People are looking for skills, and they might read a skill in a book, and then they just kind of pass by it, and they don’t remember it to implement that skill. If they had the cards in their hand and they didn’t have to read it like a book, and they go, “Huh, that’s a great idea. I should do this,” they could just put it up on their refrigerator, stick it on their computer screen, take a photograph of it and use it as a screensaver or whatever. Because the idea is, if it’s in sight, it’s in mind — rather than out of sight, out of mind.

And it kind of took off. I have almost sold 10,000 copies now. It’s being distributed by Simon & Schuster, so I could not have gotten luckier. And they told me last month they’ve given it evergreen status, which means they’ll continue to produce it. It’s not just a holiday item, which is how it initially got released.

KG: What are a few of the most popular tips?

PM: So often people are told: “When you’ve got a list of tasks to do, make sure you do the most important thing first.” If you have ADHD, sometimes that can overwhelm you. And if you feel overwhelmed emotionally, then you get demotivated. And task initiation is one of the executive functions that we struggle with. So, I flipped it around, so one of the tips is do it backwards. Do three of the easy things on your list. Get those over with in the first 10 minutes of the day. And often what happens is, if you’ve checked two or three things off your list and you’ve gotten up out of your chair and you’re moving and you’re rolling, that gives you the momentum to then take on the most important thing. Little things like that are what’s in this deck, just things that you might not have thought about yourself.

KG: Tell us about the two sides to each card.

PM: People with ADHD are incredibly hard on themselves. They have often experienced tremendous amounts of criticism, like, “What’s wrong with you that you can’t remember your book bag?” Or “How many times do I have to tell you to do this?” It gets internalized. So, people with ADHD are constantly beating themselves up. That makes your ADHD worse all day long.

What I really like about the cards is that on one side, there’s an actionable tip. For example, the one that I just grabbed says, “Schedule play throughout your day.” Maybe you sketch or jog or play your guitar for a few minutes. That might just give you the energy to move on to the next thing. But on the other side of every card is a positive affirmation. This one is: “A time for play fuels my day.” It’s just a reminder to think positively, because that does not come naturally to people with ADHD. So, of all the things that the deck puts forward, I hope it is self-acceptance, self-affirmation, be easier on yourself. And I think that’s a really helpful thing for people with ADHD to try to master. If your thinking is negative, it takes some work to unlearn it. …

I’ve been thinking about the deck for five years. You can only put 60 words on each card. That’s three sentences, and they have to be really good sentences. So, I would write and write and write and just cut it down and cut.

KG: Tell us how you came to have an Instagram account with more than 250,000 followers providing daily strategies for living with ADHD — and what is your most popular advice?

PM: I often coach people on how to find someone to see you, how to prepare for that first appointment — especially women. So many women have gone to see their primary care physician, mentioned ADHD and then been dismissed or not taken seriously. And often it’s because they just kind of throw it out there without any preparation. Make sure that you don’t ask about ADHD when your hand’s on the doorknob. Make sure that (the doctor knows) that this is the only thing you want to talk about in this appointment. You set it up that way. Write down stories in your life that demonstrate how you’ve been challenged by your ADHD. I hear from dozens of people who got a diagnosis. So, it’s helped people. That brings me great joy.

KG: I have one more social media question for you. You have the best glasses on Instagram. How many pairs do you have?

PM: No one wears a tie anymore, so I have this wonderful collection of eyewear. I even got a sponsorship at one point on social media. It’s just fun to change ’em up. I love it. I generally wear round specs. And so those come in lots of colors. They’re a great accessory, and now it’s affordable online, whereas it never was before.

KG: Going back to your time at Wake Forest, what are your memories from your time on campus in the late ’70s and early ’80s?

PM: During my time on campus, Scales Fine Arts Center was (new). It was very controversial because the building was fairly modern, and it didn’t match all the Georgian architecture on the rest of the campus. I was in music and in theater, and it was a joy to be in that building. It was amazing.

I remember all the concerts that were in the chapel, and I also sang in the choir there every Sunday. I saw Pat Benatar there.

KG: Perry, now that you’ve created this publication, what’s next?

PM: If they continue to do well, there’s probably a second deck in the hopper, and that will be for women only. Women aren’t diagnosed until much later in life — their average age of diagnosis is 37. That’s the average. And these women have had it since they were children. Most women are aware that they struggle, that they’re disorganized, that things don’t go smoothly for them, but they don’t ever ask for help.

There are sexist practice patterns where women get diagnosed as being depressed or anxious, without any idea what can be fueling their depression and anxiety. Our girls are willing to work harder than boys, so they’re able to adapt to their ADHD without a diagnosis better than boys are. Girls internalize their symptoms. Their ADHD is often the inattentive type. Whereas boys are disruptive and get discovered.

I have a lot of followers on Instagram (who) are women in their 40s, 50s, 60s. So, the next thing I write will be about all the different aspects of being a woman with ADHD from puberty all the way through pregnancy, breastfeeding, perimenopause, menopause, etc. As estrogen goes up and down, it affects your dopamine. So, I think there’s a lot to talk about that would be helpful to women.