Opening Art by Jessica Hische

Innovation Quarter: A Small Town in the Making

Work, live, learn, play.

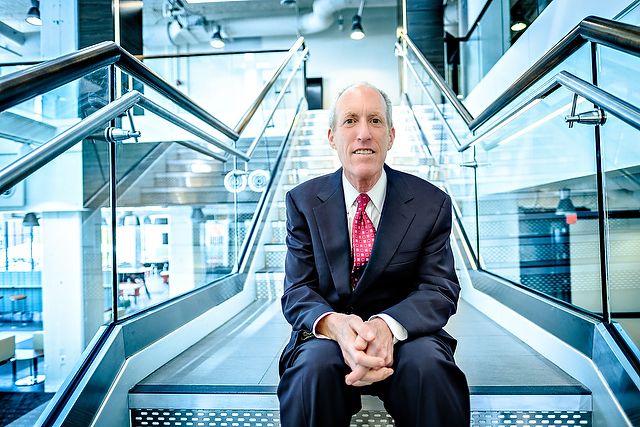

That’s the mantra at Wake Forest Innovation Quarter, said its president, Eric Tomlinson.

He might need to add “grow” to the list, because this fast-developing district for innovation in research, education and business is bursting with new projects, including the expanded presence of the School of Medicine’s education programs two months ago and the upcoming addition of a group of Wake Forest undergraduate students in January. Next fall semester, Wake Forest will launch an undergraduate engineering program in Innovation Quarter.

“By the end of 2017, we’ll have a small town here,” said Tomlinson, who is also chief innovation officer at Wake Forest Baptist Medical Center.

By then, Innovation Quarter will have grown from 3,100 to about 3,600 people working there and 60 to at least 70 companies and five institutions represented: Wake Forest University, Wake Forest Baptist Medical Center, Winston-Salem State University, Forsyth Technical Community College and the University of North Carolina School of the Arts. Innovation Quarter will have attracted about $800 million in investment, Tomlinson said.

By then, Innovation Quarter will have grown from 3,100 to about 3,600 people working there and 60 to at least 70 companies and five institutions represented: Wake Forest University, Wake Forest Baptist Medical Center, Winston-Salem State University, Forsyth Technical Community College and the University of North Carolina School of the Arts. Innovation Quarter will have attracted about $800 million in investment, Tomlinson said.

The beginnings of Innovation Quarter bubbled up in the early 1990s with local leaders studying a potential research park downtown to help the dwindling tobacco and textile economy. They secured state seed money in 1993. In 1994, eight Winston-Salem State University researchers began working with Wake Forest medical school’s Department of Physiology and Pharmacology in a former tobacco building. By 1998, an alliance of academic, education and business leaders was promoting Piedmont Triad Research Park. Wake Forest Baptist Medical Center eventually bought the first building erected there in 2000, One Technology Place. The park was renamed Wake Forest Innovation Quarter in 2013.

Wake Downtown, as Wake Forest is calling its campus extension, is a crucial element for Innovation Quarter’s future, Tomlinson said.

“The fact that the University is establishing an undergraduate program in engineering is a phenomenal step forward,” he said. “That will lead eventually to skills and capabilities in engineering in the city that we haven’t had. It’s going to have a huge impact if we can get those programs right and provide the graduates of that program with a reason to stay in Winston-Salem. That can then foster all types of new innovation as those students work next door to med students next door to biomedical engineering next door to big data next door to incubation space. It’s a very, very significant step for Innovation Quarter and for the city as a whole.”

Forsyth Tech brings about 6,000 workforce students a year to Innovation Quarter, and 1,100 students will be studying there in formal degree or training programs by the end of 2017. The area also is attracting housing; by mid-2018 Tomlinson expects there will be about 1,200 apartments in or contiguous to Innovation Quarter.

The recent addition of Bailey Park, with green space and an amphitheater, has brought yoga classes, food trucks and concerts to the area. Announced in April was a plan to move ahead with renovating the defunct Bailey Power Plant across Patterson Avenue from the park. The plant will feature office, entertainment and retail space. And just a few blocks away are the Arts District on Trade Street and Restaurant Row on Fourth Street.

The recent addition of Bailey Park, with green space and an amphitheater, has brought yoga classes, food trucks and concerts to the area. Announced in April was a plan to move ahead with renovating the defunct Bailey Power Plant across Patterson Avenue from the park. The plant will feature office, entertainment and retail space. And just a few blocks away are the Arts District on Trade Street and Restaurant Row on Fourth Street.

“So there’s a richness here of approach that you wouldn’t find in, say, a classic research park where people drive in and drive out,” Tomlinson said. “We’re a highly wired community, with proximity of businesses and institutions coexisting in inspirational spaces leading to unique collaborations.”

Tomlinson said to expect another big development in the coming months that is “just going to blow people away.”

“By the time we’re finished in 10 to 15 years’ time, we estimate another $800 million will have been invested into Innovation Quarter,” he said.

With its New Space, Medical School Aims to Become U.S. Model

“Undergraduates shuttling to class downtown” has the ring of a big headline, but the School of Medicine is making its own news as its educational approach evolves.

In July, the medical school and its graduate programs in biomedical sciences moved into Wake Forest Innovation Quarter from the campus at Wake Forest Baptist Medical Center on “Hawthorne Hill.” Medical students, educational faculty and administrative staff joined investigative faculty, graduate students and postdoctoral fellows who had moved there earlier to take advantage of the research labs in Wake Forest Biotech Place in Innovation Quarter.

“We’ve always had a wonderful curriculum, but the new building allows us to move to another level where the curriculum can be highly innovative and nation-leading,” said Dr. Edward Abraham, dean of the School of Medicine.

Interdisciplinary teams are the new model for health care, he said. “The students in all these disciplines need to learn together and how to function as a team,” he said. “Proximity is really important. … The fact that the space for all of our educational programs is contiguous allows for group learning, which was so much more difficult in our previous separate locations.”

Medical students moved from scattered spaces in Wake Forest Baptist Medical Center into the much more spacious, renovated building called the Bowman Gray Center for Medical Education. It will house 70 full-time faculty and staff, and 190 of about 1,200 faculty members will teach there at various times. Much of the faculty will continue to work at the medical center and other sites.

Dr. Edward Abraham, the medical school dean, says the new building is designed to increase student engagement. “Information sticks better if you have to grapple with it.”

Administrators visited state-of-the-art medical schools around the country before designing the spaces at Innovation Quarter. An $850,000 grant from Duke Endowment supported a new simulation facility, which can be configured in different ways.

“We can have a simulation of a ‘patient’ arriving in the emergency department, and we can have a resuscitation there, then the patient would move into another simulation facility next to it like an operating room, then into an intensive-care unit,” Abraham said. “We can model team interactions in ways that we absolutely couldn’t before. There are multiple other examples, too.”

In the new building, he said, “students will be able to go into simulated exam rooms with actors and actresses providing patient experiences, where the students will be videotaped and graded on their interactions.” The students will continue to see real patients in hospital, outpatient and clinical settings.

“This will be the most contemporary medical education building in the country and a model for other institutions,” Abraham said. The improvements should enhance what is already one of the 10 most competitive medical schools in the country in terms of admissions.

Donna Boswell (’72, MA ’74), who chairs the University’s Board of Trustees and advised businesses in her law practice before retiring, said Abraham had already established a creative environment with researchers and businesses in “research neighborhoods” in Innovation Quarter. The physician assistant and certified registered nurse anesthetist graduate programs already were there, along with the Division of Public Health Sciences.

Now medical students will benefit, too, she said. In their previous location, students could experience the hospital, “but current medicine is not all in the hospital. It’s more in settings in which we try to build healthy lives.”

Stitching Together Campuses Requires Precision

It’s hard to understand why Emily Neese’s mind isn’t thoroughly boggled by the Wake Downtown project.

Neese (’81, P ’13, ’16), associate vice president for strategy and operations, is coordinating with more than 50 committees and subgroups to make sure students and faculty have everything they need to study, work and play on the new downtown campus at Wake Forest Innovation Quarter. When preparing for a move, nothing is as simple as it first seems.

This logistical challenge starts with the shuttles that will need to go between the Reynolda Campus and downtown Winston-Salem about 4.5 miles, or 12 minutes away. The University expects to run shuttles from 7 a.m. to 11 p.m. every 15 minutes, with Reynolda Campus riders able to catch a shuttle within a two-minute walk. They will be dropped off at the front door of the Wake Downtown undergraduate building, a renovated tobacco building.

“We are committed to a robust shuttle service that will ensure that students will choose to ride the shuttle instead of attempting to drive downtown, which means it has got to be really convenient on both ends, both in terms of pickup and drop-off locations and timing,” Neese said. “We are emphasizing both convenience and the safety of our faculty and students when we talk about transportation.”

Once class schedules are in place, she said, planners will operate from the assumption that someone on campus will start the journey just 15 minutes before needing to be at Innovation Quarter. By 2021, an estimated 350 students will be going downtown, but that number will grow slowly, “so we’ve got time to monitor and ramp up transportation,” Neese said.

Emily Neese has worked with dozens of groups on Wake Downtown logistics, from shuttles to computer networks.

That’s a good thing, because the deadlines for starting Wake Downtown are unforgiving. Two historic tobacco buildings donated by Reynolds American have been undergoing major renovations by Wexford Science & Technology, a developer that specializes in science buildings and laboratories. One building houses medical students and faculty. The other next door will be home to undergraduate education.

The project takes advantage of state and federal tax credits that save about 50 cents on the dollar for the $100 million project. The credits expire at the end of 2016, so moving in by then is crucial. “We are on an aggressive construction timeline until mid-December, when we hope to have our certificate of occupancy,” Neese said.

The University will have a 15-year lease with a couple of renewal options, she said.

The project created the opportunity for greater collaboration between the medical school and the Reynolda Campus, which historically have not shared services but came together to create a seamless building management plan. The goal is to make the two buildings feel like one interactive building, Neese said.

The security plan is to have multiple security officers at all times and a sworn police officer, such as those on the Reynolda Campus, on duty from 7 a.m. to 9 p.m., the high traffic times for undergrads.

Sharing wireless network connections turned out to be harder than expected. Medical networks have different privacy and patient security issues, but planners didn’t want to force anyone to log out and sign into a different wireless network as students and faculty move between the buildings, Neese said. The planning group has found creative solutions using the medical center’s network with appropriate security layers, she said.

Sharing wireless network connections turned out to be harder than expected. Medical networks have different privacy and patient security issues, but planners didn’t want to force anyone to log out and sign into a different wireless network as students and faculty move between the buildings, Neese said. The planning group has found creative solutions using the medical center’s network with appropriate security layers, she said.

Similar discussions are taking place around such services as physical and mental health care, learning assistance, academic advising and recreation. Will the buildings need one or two sets of Environmental Protection Agency permits and technicians? Can first-year-student activities integrate the newest students downtown? The questions have been daunting.

Rebecca Alexander, associate chair of the chemistry department and director of academic planning for Wake Downtown, also is focused on logistics, particularly for the academic experience.

Rebecca Alexander, associate chair of the chemistry department and director of academic planning for Wake Downtown, also is focused on logistics, particularly for the academic experience.

“How do we make it as easy as possible for students to satisfy their degree requirements? For classes with multiple sections, can we have downtown and Reynolda Campus offerings?” said Alexander. “How do you make sure, if a student is taking a class downtown, they can get back for other classes or meetings with a minimum of back-and-forth time?”

Wake Downtown will have offices for Alexander and six other chemistry faculty members and four biology faculty members, while other offices remain in Salem and Winston halls. The building downtown will need “touchdown space” or “office hoteling” for those who teach just one course there or need to meet with students, Alexander said.

Splitting departments between campuses is one of the faculty’s concerns, she said, given that “Wake Forest has always been tightly knit.” Of course, some faculty are so busy they rarely see each other even on the Reynolda Campus and might as well be miles away from each other, she said.

“At the same time, as we’re establishing a new community,” she said, “we don’t want to lose out on the community that’s here and very deeply rooted. So it will take a little bit of extra work.”