troll through Reynolda House Museum of American Art, past the study where R.J. Reynolds died and where Harry Truman napped before speaking at the groundbreaking for Wake Forest’s new campus. Continue past Katharine Smith Reynolds’ study, where Reynolda House’s matriarch oversaw a 1,000-acre farm, gardens and working village modeled after an English version.

R.J. and Katharine Reynolds and their four children moved into their “country bungalow” just before Christmas in 1917. The two-story reception hall — where family weddings and funerals took place — was restored to its original appearance by granddaughter Barbara Babcock Millhouse in 2005.

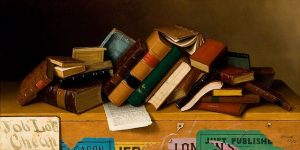

Hanging in the library of the historic house turned art museum is William M. Harnett’s 1878 masterpiece, “Job Lot Cheap.” The painting of a jumbled pile of old books resting on top of a crate full of new books happens to be a favorite of museum Executive Director Allison Perkins: “Those used volumes contain essential bits of our (American) history, so, as much as I love new ideas, I’m not an advocate of getting rid of the old; don’t let the new usurp the space of the old.”

William Michael Harnett, Job Lot Cheap, 1878, oil on canvas, 18 x 36 inches, Courtesy of Reynolda House Museum of American Art

It’s an apt metaphor as Reynolda House celebrates two milestones in 2017: the 100th anniversary of Reynolda House and the 50th anniversary of its second life as a museum of American art. Like Harnett’s juxtaposition of old and new, how does Reynolda hold on to its storied past while ensuring that it remains relevant in the future?

Museum Executive Director Allison Perkins: Reynolda House’s future lies in “stitching” together the historic house, gardens and village and sharing stories about the estate, the art collection, and the people who lived and worked at Reynolda.

“The story of Reynolda is a series of chapters in the trajectory from family home to museum of American art. The bedrock of what we do in the future will be shaped by storytelling,” says Perkins, who was named executive director of Reynolda House in 2006 and associate provost for Reynolda House and Reynolda Gardens in 2015. The stories of the people — the Reynolds family, the staff who lived in Reynolda Village, the African-American workers who lived in Five Row — make Reynolda relevant a generation later, Perkins says.

Some African-American farm workers and their families lived in the nearby Five Row community.

Reynolda was the vision of Katharine Smith Reynolds and funded by husband R.J.’s tobacco empire, which fed Winston-Salem’s growth in the early part of the 20th century. Katharine, R.J. and their four children moved into the 64-room bungalow just before Christmas 1917. Their time in the house was short. R.J. died just seven months later, Katharine in 1924.

Photographs of Nancy Susan Reynolds and Mary Reynolds Babcock.

Their oldest daughter, Mary Reynolds Babcock, and her husband, Charles Babcock (LL.D. ’58), eventually bought the estate from other family members. But by the end of World War II, Mary Reynolds Babcock was increasingly worried about the rising costs to maintain the estate. A plan to sell 500 acres as the site of a veterans’ hospital succumbed to fierce opposition. “Everyone I asked blew up over Reynolda becoming a vets’ hospital,” she wrote in a letter to sister Nancy Susan Reynolds (L.H.D. ’67). “I guess Reynolda will go on to live a longer life and end as an ancient ruin.”

"The bedrock of what we do in the future WILL BE SHAPED BY STORYTELLING."

year later, the Babcocks found another, more palatable use for part of the estate. After the Z. Smith Reynolds Foundation offered Wake Forest College a large annual gift to move to Winston-Salem from Wake County, the Babcocks offered 300 acres of the estate for the new campus. They later donated Reynolda Village and Reynolda Gardens to Wake Forest and sold off much of the remaining land until only Reynolda House and 19 surrounding acres were left.

Barbara Babcock Millhouse and Mrs. M.C. Benton, wife of the Winston- Salem mayor, open Reynolda House to the public in 1965; Reynolda House Museum of American Art opens two years later.

In the mid-1960s, Charles Babcock reimagined Reynolda House as a “center for … the arts” and appointed daughter Barbara Babcock Millhouse (L.H.D. ’88, P ’02) president of the new Reynolda House board. At first, they opened the house Wednesday afternoons and one Sunday a month to curious townfolk. Thousands of people came to see how the rich and famous once lived. But Millhouse worried that the house itself wasn’t enough to continue to attract crowds. “We didn’t understand the full significance of the historic house at that time,” she said. “Reynolda was part of a much broader phenomenon, the American Country House movement. That made the house much more important in terms of the country’s history, but we didn’t know that then.”

What she did know was that large crowds were coming to see a “picture of the month” featuring works borrowed from museums and Reynolds family members. When Stuart Feld, then a curator at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, lectured at Reynolda House, Millhouse asked him for advice on buying art for the house. His answer? Buy American. At the time, critics and scholars dismissed the value of American art. Millhouse, who was a serious art collector but not of American art, sensed an opportunity. With $300,000 raised from family and family foundations, and with Feld as an adviser, Millhouse and the Reynolda board could buy topnotch American art for a relatively small sum.

Wake Forest freshmen visit Reynolda House during orientation in 2010 to study Frederic Edwin Church’s “The Andes of Ecuador” (1855).

"As much as I love new ideas, I'm not advocating getting rid of the old; DON'T LET THE NEW USURP THE SPACE OF THE OLD."

eynolda House opened as a museum in 1967 with nine paintings that are now among the museum’s most famous works including Frederic Edwin Church’s “The Andes of Ecuador” (1855), William Merritt Chase’s “In the Studio” (1884) and Albert Bierstadt’s “Sierra Nevada” (1871-1873). The timing was perfect; interest in American art — and prices — skyrocketed within a few years.

The poolhouse was added to the bungalow in 1937 and restored in 2014.<br /> Photo by Lauren Martinez Olinger ('13), Red Cardinal Studio.

ith a keen eye and passion for art, Millhouse continued to build the art collection in the 1960s and ’70s. The collection has grown to include more than 200 paintings, drawings and sculptures showcasing three centuries of American art by such artists as John Singleton Copley, Charles Wilson Peale, Mary Cassatt, Thomas Eakins, Jacob Lawrence, Grant Wood, Roy Lichtenstein, Georgia O’Keeffe and Stuart Davis. The opening of the Mary and Charlie Babcock Wing in 2005 provided modern gallery space for changing exhibitions from around the country to complement the permanent collection. Record crowds have turned out in recent years to see blockbuster exhibitions on Ansel Adams and American Impressionism.

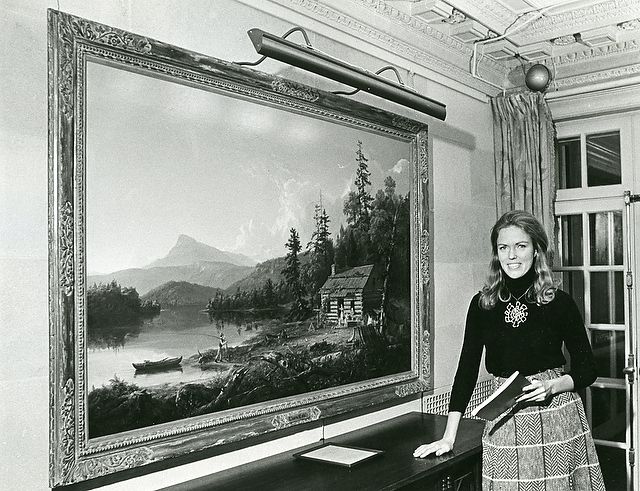

Barbara Babcock Millhouse in 1973 with Thomas Cole’s “Home in the Woods” (1847).

No one knows more about Reynolda or has written more of its story than Millhouse. She never knew either of her grandparents, but she lived at Reynolda at times as a young girl. She has a masterful memory of all things Reynolda, down to what was originally on the walls: “Mirrors. And a couple of dark Rembrandt-like family portraits.” She also has a scholar’s obsession for historical accuracy — from finding out how the telephone system operated in the house to the type of light bulbs: GE Mazda bulbs. She led an interior renovation of the house in 2005 that restored the public rooms to their 1917 appearance.

Reynolda House’s Katie Womack, assistant director of collections management, and Che Machado, preparator, carefully move “Mrs. Thomas Lynch” (1755) by Jeremiah Thëus.

think a lot of my energy comes from the fact that it makes me feel like I still have a family,” says Millhouse, who lives in New York City but also has a house in Winston-Salem within walking distance of Reynolda. “My parents both died young. My father died right after the opening (of Reynolda House in 1967). He had a great curiosity. It was almost like he was staying alive to see that happen.”

Millhouse has long sought to bring Wake Forest and the Reynolda Estate — Reynolda House, Reynolda Gardens and Reynolda Village — closer because of their shared history. “My father disbursed the property, and now we’re putting it back together,” she said in 2002 when announcing an affiliation agreement with Wake Forest. The agreement kept Reynolda House’s independence as a separate nonprofit institution but placed it under the University’s umbrella.

“Stitching” the estate back together is vital to telling the story of Reynolda as a prominent example of the American Country House movement with a model farm and working village, Perkins says. Already, new signage, landscaping and pathways are better connecting the house, gardens, village and Wake Forest’s campus. “It’s really important to think about historic Reynolda as one place,” she says. “All of the properties — Reynolda House, Reynolda Gardens and Reynolda Village — share the same birthright; they were siblings. When you stitch these historic properties back together, that creates a whole place.”

Integrating stories about Reynolda House, its history and artwork will define Reynolda’s second century, Perkins said. “When you factor in our historic site and our amazing art collection — which rivals anything south of D.C. — and you blend that with the exceptional talent of our (University) faculty and staff, I can’t find a peer institution that matches what we have.”

Join the Celebration

Reynolda’s centennial year launches in July and concludes next spring. The museum is hosting two major exhibitions to mark the centennial: “Georgia O’Keeffe: Living Modern” opens in August following its initial showing at the Brooklyn Museum; and “Frederic Church: A Painter’s Pilgrimage,” opens in February 2018 after its debut at the Detroit Institute of Arts Museum.

The museum also plans to enhance visitor experiences with a new book about the art collection and a mobile audio-visual tour featuring stories about Reynolda House, the art collection, and the people who lived and worked at Reynolda. The museum’s ongoing $5 million capital campaign, “Reynolda at 100,” already has funded improvements to the historic house, and restoration of the 1930s-era indoor pool and landscaping around the house.

"So much of Reynolda's restoration HAS SEEMED LIKE MAGIC."