What’s the best way to live?

Perhaps answering that has never been easy, but it can seem more difficult today as the speed and depth of cultural, political and technological changes add a few kilotons of pressure to the game of life.

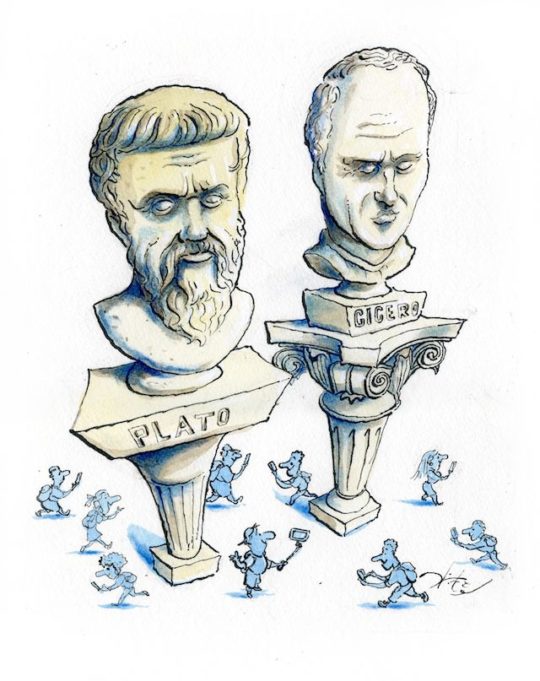

We decided to look back into time — way back — to see what advice the classical philosophers of Greece and Rome might offer for living a better life. (Of course, they are not the first or only source of humankind’s playbooks, but they are an important chapter from the Mediterranean region of Europe from about 800 B.C. to 400 A.D.)

The writings of Socrates, Plato and other oldies-but-goodies delve into the many complexities of philosophy. What are essential takeaways? Three professors agreed to share their views.

From Professor MARY PENDERGRAFT, who chairs the Department of Classical Languages:

- Have honest confrontations with our uncertainty and be wise enough to know the limits of our wisdom.

- Ask uncomfortable questions.

- Prize doing the right thing even more than staying alive.

Pendergraft said Plato made these points in his Apology of Socrates to show that Socrates (circa 469-399 B.C) was wrongfully executed after he was found guilty of politically motivated charges that he had “corrupted the youth” of Athens. (“Apology” is simply the Greek term for a defendant’s speech in court.)

This was the first Greek text that Pendergraft read as a college freshman in 1972, and it fascinated her. Americans at the time were protesting the Vietnam War and discovering the Watergate corruption scandal that would force President Richard M. Nixon to resign. She was seeing the relevancy of speaking truth to power and having moral courage.

Plato (circa 427-347 B.C.) noted Socrates’ surprising view that even if your enemies kill you, “a good man cannot be harmed either in life or in death, and that his affairs are not neglected by the gods,” Pendergraft said. He was saying that living justly is more important than any physical harm you face, she said.

Today, powerful people often are unwilling to recognize the limits of their knowledge, she said. “We’ve got a great example of people in power who don’t examine their preconceptions, or whether there are other ways of understanding, or whether their presentation of ideas is reasonable or correct or just in any way.”

Coming back to these touchstones reminds us that “money and power are not more important than living in justice, and knowing exactly what you know or how little you know is also important in figuring out the right way to live,” Pendergraft said.

From MICHAEL C. SLOAN, associate professor in the Department of Classical Languages:

- Make a habit of refusing immediate urges. If you can say no to small impulses, you can begin to say no to big ones.

- Increase your appetite for the good and beautiful, but diminish your appetites for that which distorts the good or is destructive.

- To control your appetite either way, you must control your eyes and ears. What you see and hear will affect you, so choose wisely what your mind and senses take in.

“Grit,” a quality in successful people who demonstrate discipline and perseverance, Sloan said, is a much-lauded buzzword in the world of leadership, character and human refinement. Grit is often valued even above intelligence and charisma. “Recent studies show that those who have grit also have the highest capacity for delayed gratification,” Sloan said. “The finding is not as new as we may think. There is a long line of classical poets and philosophers who swam in that river.”

Sloan said the Roman poet Lucretius (circa 99-55 B.C.) witnessed a period of demagoguery, fallow fields and many revolts threatening to overthrow the government. Lucretius saw the results of unchecked greed and appetites, and he called on Romans to control their senses.

In his philosophical treatise On Moral Duties, Roman politician and philosopher Cicero (circa 106-43 B.C.) taught his son: your eyes control your mind, your mind controls your actions, and your actions are your character, Sloan said.

“To exhibit good character, grit and responsible leadership qualities, we must guard our mind and appetites, which means if we follow Lucretius and many other ancient poets and philosophers, we must guard our eyes and ears.”

If you’re seeing a trend here that these philosophers emphasized virtue as key to happiness, you’re right. From EMILY AUSTIN, associate professor in the Department of Philosophy who specializes in Greeks of yore:

- You can be wrong about whether you’re happy.

- Virtue is necessary for happiness, so the vicious — however wealthy and powerful they might be — cannot be happy.

- Desires for wealth and honor are the greatest impediments to cultivating virtue.

Greek ethical philosophy starts from a psychological assumption that guides pretty much everyone: we want to be happy, Austin said. But the Greeks — the philosophers, if not the man on the street — didn’t define happiness the way we generally do, Austin said. They called it eudaimonia (ew-dye-mon-EE-ah), and they believed it was an objective thing, like saying water is H2O, not a subjective feeling, she said.

This can seem strange to us, Austin said. We know unethical people who say they are happy, and we know many morally upstanding people who are nevertheless wracked by unhappiness.

“We don’t want people to tell us we’re not happy when we take ourselves to be. That seems like an affront to us, but we’re often actually happy saying this about others,” Austin said. We may say that a person in an abusive relationship thinks he or she is happy but really isn’t. We may say our friend thinks he is happy in a career when we see him as obviously in the wrong job.

There are certain challenges to the idea that happiness requires virtue, such as the tyrant or psychopath who relishes bad behavior. “The ancients are just going to push their finger in your face and be like, ‘Do you really think that is happiness? Really?’ ” Austin said. “Plato says when you’re vicious, your soul lacks harmony, so you’re going to have some tension in your soul between your beliefs and your desires.”

How storytelling distinguishes the ancient Greeks in history

More on Greek wisdom from Michael C. Sloan, associate professor of classical languages

More on Greek wisdom from Emily Austin, associate professor of philosophy