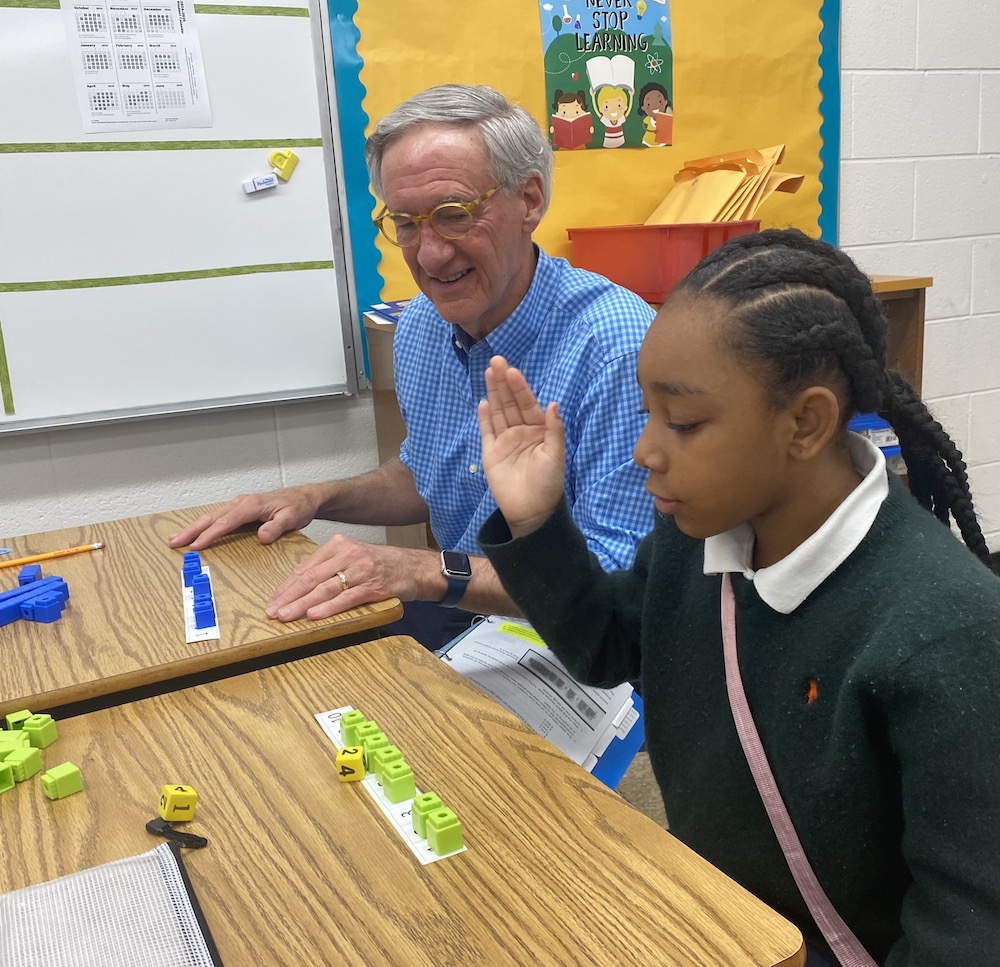

On a recent rainy Wednesday morning, Ingram Hedgpeth (’76, P ’05) is taking turns with a third grader rolling dice onto a kid-sized desk at Bolton Elementary School in Winston-Salem.

It might have looked like a game, but Hedgpeth is helping the young girl learn how to make number combinations up to 10. When she rolls the dice and correctly adds the numbers to eight, he asks her, “What other numbers make eight?”

“Seven plus one, five plus three, four plus four,” she answers. “One more,” he says gently. “Six plus two,” she responds. As they continue rolling the dice, her confidence grows as she quickly adds numbers and places lime-green blocks on the appropriate numbers on a strip of paper.

“You are so on today,” Hedgpeth tells her.

“I couldn’t do that last week,” she admits.

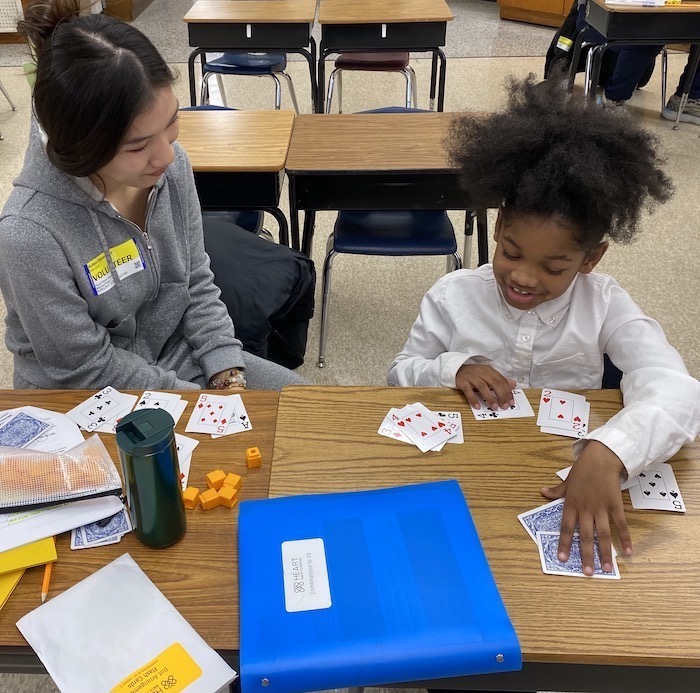

Hedgpeth is one of about two dozen Wake Forest alumni, students and staff who tutor students at Bolton and Easton elementary schools in Winston-Salem through the Heart Math Tutoring program. Tutors work one-on-one with the same student each week to improve their foundational math skills. The Wake Foresters are among about 120 volunteers who tutor 100 students at the schools. (The students’ names are being withheld to protect their privacy.)

“It’s called Heart Math for a reason. We lead with the heart, and the math follows,” says Hedgpeth, a retired Presbyterian minister who, with his wife, Marilyn Hedgpeth (P ‘05), volunteers at Bolton once a week. “I get the joy of having some small part in the life of this child for 30 minutes a week,” he says.

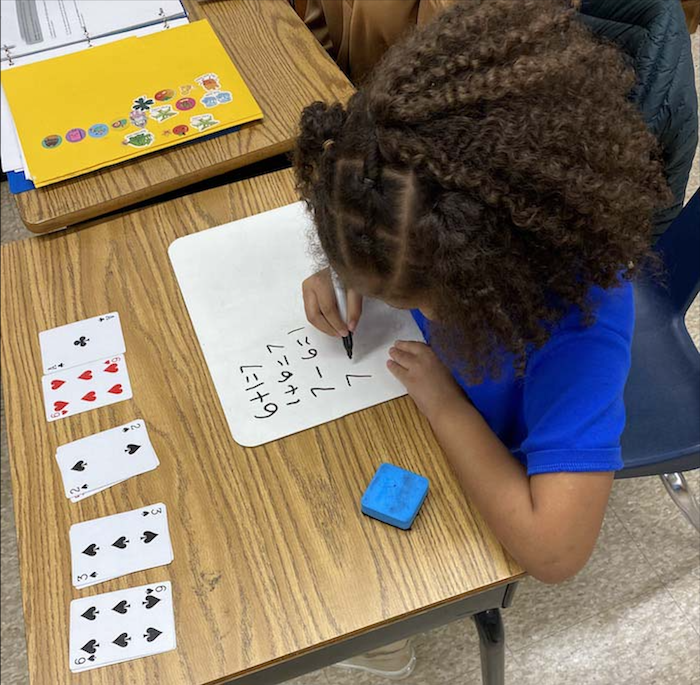

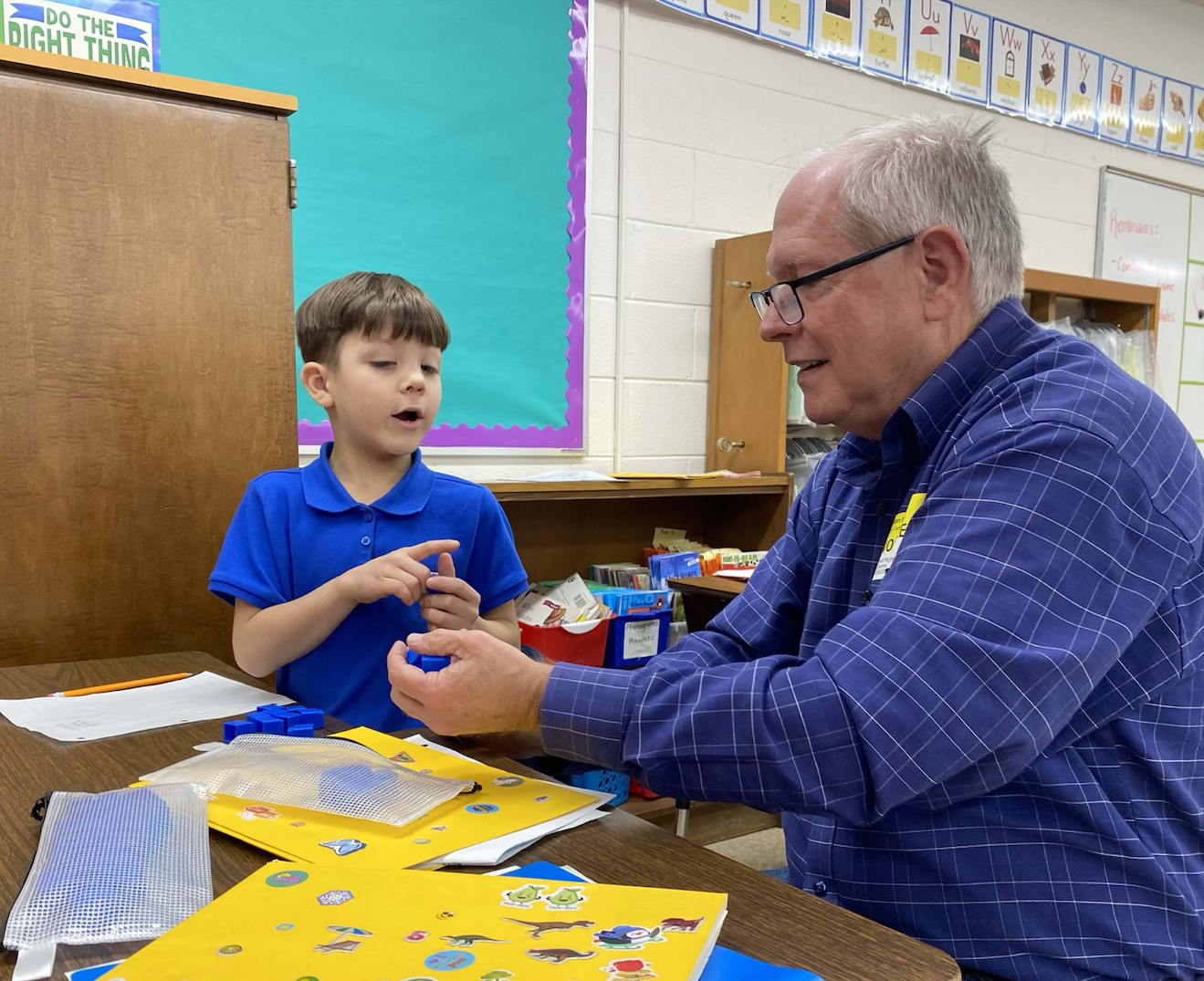

Heart Math Tutoring provides tutors step-by-step instructions for the activity-based lessons, which incorporate dice, cards and blocks to make math easier to understand for tactile or visual learners. Corporate, foundation and individual gifts fund the program, which includes on-site coordinators at each school to support volunteers.

Heart Math was founded in 2010 in Charlotte to help students struggling with math at economically disadvantaged schools. The nonprofit is serving about 1,150 students with about the same number of tutors at 23 schools in Charlotte this year. Thanks to Wake Forest alumni, the program has expanded to Winston-Salem and Charleston, South Carolina, in the last few years.

Claire Bennett Devon (’18) “fell in love” with Heart Math when she was a tutor in Charlotte and helped bring the program to Winston-Salem in 2023 after she moved here.

“Working with the same student, you develop a special relationship and become ‘their’ person,” says Devon, chair of Heart Math’s Winston-Salem board and a director of Front Street Capital in Winston-Salem. “For some, you are an extra adult mentor and for others, you might be the only one. It’s about 50% being a math tutor and 50% being a positive role model who offers encouragement.”

John Cooper (’72, MA ’73) is one of Heart Math’s most enthusiastic Wake Forest supporters. After reading a 2016 Wake Forest Magazine story on the Charlotte program, he was determined to bring the program to Charleston. “That was absolutely the catalyst,” he says. “We had a tutoring program for reading, but there was no tutoring available in math for kids who couldn’t afford it.”

Cooper knew two alumni on the Heart Math Charlotte board: Connie Herr Carlson (’87, P ’15, ’19), at the time the Charlotte board chair, and Eric Eubank (’86, P ’15), a Wake Forest trustee. They were looking to expand the program, and Cooper encouraged them to consider Charleston. The program started in one school in Charleston in 2022 and has since expanded to serve more than 170 students in four schools.

Cooper, who is retired, tutors two students for 30 minutes each once a week. “It’s an extremely rewarding part of my week to hear a student say that math is their favorite subject, even though it may not be their best subject,” he says. “If students are behind in third grade math and reading, and they stay behind … then unfortunately, a good part of their life script has been written.”

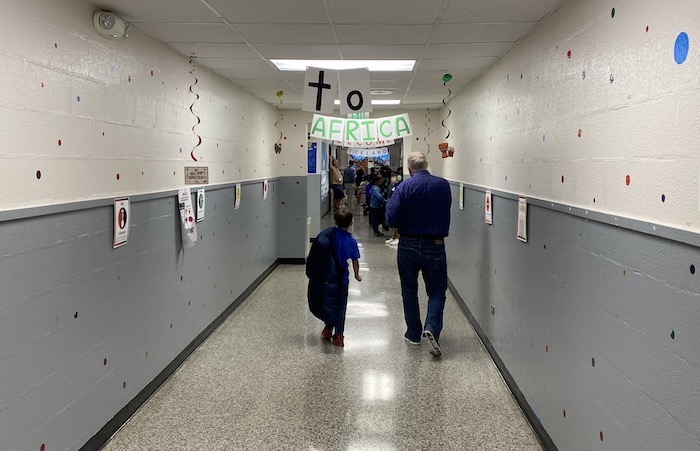

Back at Bolton Elementary School in Winston-Salem, a handful of Wake Foresters walk down hallways decorated with colorful signs and a large multicolored caterpillar hanging from the ceiling. They accompany their students from their regular classrooms to a classroom set aside for tutoring. Letters on the classroom door offer inspiration: “ALWAYS believe that something WONDERFUL is about to happen!”

Most of the volunteers on this day are helping their students learn how to add and subtract numbers up to 10 and practicing the different combinations that make up 10. Stan Clarkson (’80) shows his student 10 blue blocks he’s holding in his hands. He closes his hands, puts six blocks on the desk and asks, “How many are left?”

At a nearby desk, Becky Maier Paynter (’01, MAEd ’04) helps her student as he counts out blue blocks. At another desk, Krista Stump, a Wake Forest employee in the sustainability office who volunteers during her lunch hour, watches as a young girl adds up numbers from a deck of cards and writes the total on a whiteboard.

Clarkson, who retired after 37 years working in the North Carolina juvenile justice system, says tutoring makes him feel more optimistic about the future. “These kids are just so sweet,” he says. “It’s very rewarding when you see growth academically … when you see kids who might otherwise struggle.”

Cheryl Frazier, the principal at Bolton, says the program has been invaluable in helping the school assess where students are in math and filling in the gaps. “They (tutors) can home in on the foundational pieces that kids are missing,” she says. “An unexpected consequence is that the kids have so much more confidence. Kids who might not have ever seen themselves as being good at math have really taken off.”

According to Heart Math, 98% of students in the program in Winston-Salem last year showed growth based on targets set by elementary math specialists; 90% of teachers reported that student confidence and/or enthusiasm toward math increased. The programs in Charlotte and Charleston showed similar results.

The bonds between tutors and students may be harder to assess, but Frazier says having an adult work one-on-one with a student shows that “someone believes in them. It broadens their horizons and gives them insight (into the world) outside the school setting. You never know how valuable those small conversations are.”

That’s why Ingram Hedgpeth and the other volunteers spend a few minutes just chatting with their students before they start tutoring. “How was your weekend?” he asks his student. “Great,” she says. Her cousin fixed French toast, bacon and eggs one morning. “She has the best breakfasts,” Hedgpeth says, before pivoting to math. “You want to do some numbers now?” he asks, as he puts the dice on the desk in front of her.

Thirty minutes later, as their tutoring session ends, Hedgpeth praises her efforts. “If you don’t know something, I can see your brain working, and you figure it out.” She’s making so much progress, he tells her, she’ll soon be ready to move on to the next color-coded binder, each of which focuses on a different concept.

No, she says quietly. She doesn’t want to move too quickly to the black binder, the one labeled, “Understanding Multiplication and Division.” That’s the last binder, the one that signals to the student that her lessons in Heart Math are nearly done.

Are you interested in volunteering with Heart Math Tutoring? Learn more.